Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Key points

- Enrolment in public elementary and secondary schools has dropped by 4% and 5% respectively over the past two decades, while enrolment in private schools has surged by 20% over the same period.

- The movement of students to private schools accounts for 26% of the decrease in enrolment in public elementary schools and 82% of the decrease in enrolment in public secondary schools between 2001–2002 and 2020–2021.

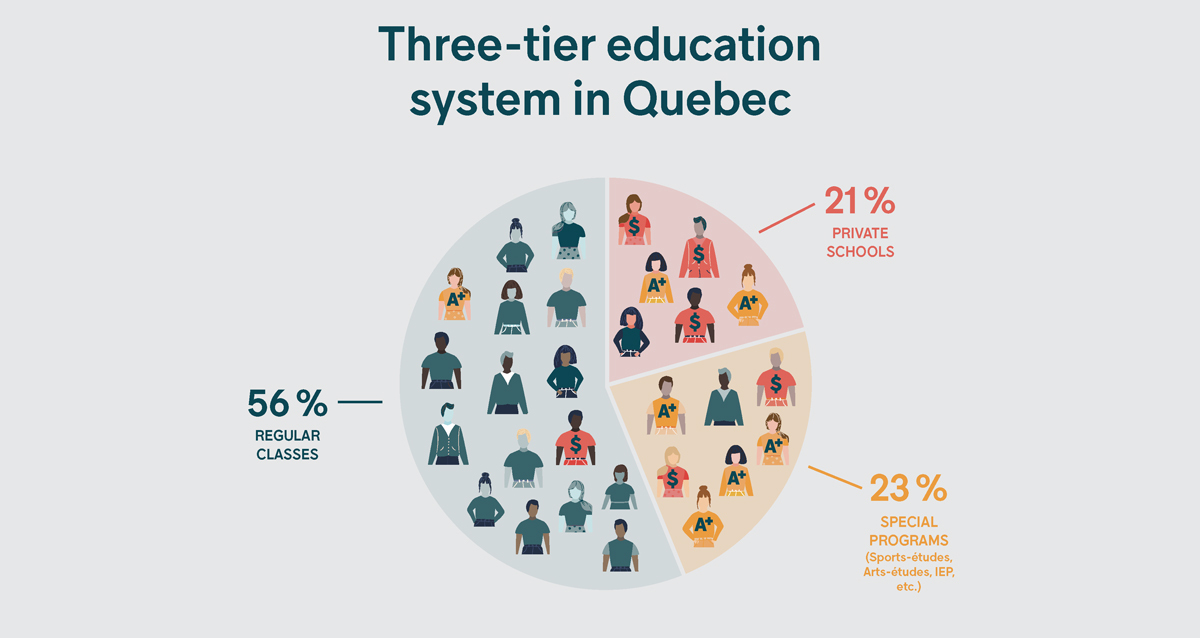

- Although the percentage of secondary school students attending private school has remained relatively stable at around 21% since 2013–2014, the regional data show a much higher percentage in major urban centres.

- The percentage of secondary school students enrolled in public special programs increased significantly over the past seven years and is now around 23%.

- At the secondary school level, 39.5% to 44% of students have been taken out of regular classes in public schools and enrolled in either private schools or in special programs at public schools.

In 2016, the Conseil supérieur de l’éducation published a damning report that found Quebec’s education system to be the most inequitable in Canada.1 The following year, IRIS published a socio-economic report showing that the segregation of students based on academic performance and socio-economic status was indeed a phenomenon in Quebec schools.2

Five years later, we wanted to find out if anything has changed with this form of school segregation, which has much to do with the reinforcement of a three-tier education system in Quebec. This update to IRIS’s 2017 report is more relevant than ever, as new calls for major educational reform are being made to reverse these trends.3

A three‑tier education system and school segregation: What it is, how it started, and how it’s going

School segregation is the separation or grouping of students into different schools or classes based on a set of factors. Examples include the history of racial segregation in Canada and the United States, as well as Quebec’s longstanding tradition of separating students by gender.

This report focuses on the form of segregation in which students are effectively separated based on their socio-economic status and academic performance. In Quebec, this segregation is caused by a three‑tier education system made up of private schools, regular classes in public schools, and special programs in public schools.4

This type of school segregation is mainly driven by competition between public schools and private schools, which is much fiercer in Quebec than in other Canadian provinces. This is because private schools receive significant public subsidies. The Ministère de l’Éducation du Québec (MEQ) foots about 60% of the bill for educational services at these schools,5 which makes them accessible to a larger portion of the population—although the vast majority of their students are still from high-income backgrounds.6 The fact that private schools receive this public funding encourages the first layer of segregation: the divide between public and private schools.

Furthermore, because private schools attract higher-performing and more socio-economically advantaged students, public schools feel compelled to create “special” programs (sport-études, arts-études, international education, academic enrichment, etc.) in an attempt to retain these students. These special programs add another layer of segregation within public schools themselves, as they too are often reserved for higher‑achieving students. What’s more, 76% of these programs require parents to pay fees.7 These fees can vary depending on the program, but parents pay $1,220 on average and may pay as much as $14,000 for the most expensive programs.8

These two layers of segregation—one between public and private, and one within the public school system itself—has a “cream-skimming” effect, in which students with lower academic performance and socio‑economic status are concentrated in regular public school programs while the most advantaged students are clustered into private schools and special public school programs. This has caused the mix of students in classrooms and schools to become significantly more homogeneous.

The negative consequences of the cream-skimming effect are profound and include the reproduction of pre‑existing social inequalities. For example, it is well established that students of lower socio‑economic status face greater challenges that can negatively affect their academic performance. The three-tier school system widens these disparities instead of addressing them. Disadvantaged students and students with learning difficulties are particularly likely to suffer when they are all crowded into the same classes, as is the quality of the education they receive. On the other hand, students with greater needs benefit from being placed in groups of mixed background and ability, without any detriment to higher‑performing students.9

Measuring school segregation

Data obtained from the MEQ through access to information requests provide insight into the extent of the cream-skimming effect and how the situation has changed over the past two decades.

Graph 1 illustrates how enrolment in general education in the youth sector has changed in both the public and private school systems at the elementary and secondary school levels since 2001–2002.

The change in total enrolment in general education in the youth sector at the elementary and secondary school levels is indicative of the effect of demographic changes on the number of children attending school. Changes in private primary school enrolment are largely independent of these demographic factors: despite a significant decline in total enrolment between 2001–2002 and 2010–2011, enrolment in these schools steadily increased through 2019–2020.

At both the secondary and elementary level, private school enrolment has risen significantly, while public school enrolment and total enrolment has declined, as seen in Graph 2. Enrolment in public elementary and secondary schools has dropped by 4% and 5% respectively over the past two decades, a sharper drop than is accounted for by the decline of the school-aged child population reflected by total enrolment numbers. Enrolment in private schools has surged by 20% over the same period.

In other words, the lower number of students in the public school system is in large part due to the recruitment of these students to private schools, not just demographic changes within their age groups. The movement of students to private schools accounts for 26% of the decrease in enrolment in public elementary schools and 82% of the decrease in enrolment in public secondary schools between 2001–2002 and 2020–2021.

Graph 3 shows that private school “cream skimming” of high-performing and socio‑economically privileged students from public schools is a particularly pernicious problem at the secondary school level: in 2020–2021, the private school student population accounted for 6% of total enrolment at the elementary school level and 20.5% of total enrolment at the secondary school level.

For Quebec as a whole, the percentage of students recruited by the private school system is similar to what was measured in 2017 for 2013–2014.10 However, these aggregate data do not take into account considerable regional variations. Table 1 provides the percentage of secondary school students attending private schools in 2013–2014 and 2020–2021 for each administrative region.

It is evident from the numbers that the percentage of secondary school students attending private school is much higher in urban centres, where a wider range of private school options are available: compare 34% in Montréal and 24% in the Capitale-Nationale region to just 5% in Côte‑Nord and Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean. In three regions, there were no elementary or secondary school students attending private school at all. And although the situation has remained relatively stable for Quebec as a whole, private school cream skimming of public school students has become more prevalent in Montréal and Laval and less prevalent in most other regions.

Meanwhile, public secondary schools have become substantially more segregated with rising special program enrolment. In our 2017 socio-economic report, IRIS estimated that approximately 14 % of secondary school students were enrolled in public special programs in 2013–2014. This number rose to at least 19% in 2020–2021, a 36% increase in seven years. While the same phenomenon in elementary schools has been on a modest upswing since 2013–2014, it is still relatively uncommon: 3.5% of elementary school students were enrolled in a special program in 2020–2021, compared to 3% in 2013–2014.

It should be noted that the data on special programs are underestimated. As the MEQ noted in its response to our access to information requests, the data include [Translation] “only students from schools that report that they offer a special program . . . The data are therefore non‑exhaustive and only partially representative of the programs that are actually offered and the students enrolled in them.”

According to its 2007 estimates, the Conseil supérieur de l’éducation found the actual number of secondary school students in special programs to be 22.7% greater than reported in the MEQ’s data.11 With this estimation applied to the 2020–2021 data, the percentage of public secondary school students enrolled in special programs is 23% rather than 19% (see Graph 3).

A comprehensive investigation of school service centres by the MEQ in 2019–2020 suggests that the percentage is in fact even higher.12 While the data provided in response to our access to information requests indicates that a total of 101,710 students were enrolled in a special program at the elementary or secondary school level in the public system, the MEQ’s investigation found the actual number to be more than twice that—214,046 students, accounting for nearly 22% of total enrolment at the elementary and secondary school levels. The findings of the investigation were not broken down by level, but this percentage is presumably much higher at the secondary school level, given that enrolment in special programs in elementary school is relatively rare.

Even without taking the MEQ’s investigation into account, it can be concluded that, at the secondary school level, 39.5% to 44% of students have been taken out of regular classes in public schools and enrolled in either private schools or in special programs at public schools.

Conclusion

The segregation of students in Quebec schools based on academic performance and socio‑economic status has not decreased. In some ways, the situation is even worse than it was when it was first assessed by IRIS in 2017. The private school system continues to put significant pressure on public schools, which have ramped up their offer of special programs in an attempt to curb the exodus of students to private schools. In doing so, the public school system is doing its own cream skimming from its regular classes, reinforcing segregation within its schools and reproducing the social inequalities inherent in segregation.

In light of this, it is time to seriously rethink how elementary and secondary school services in Quebec are organized. Various reforms have been proposed in recent years, including eliminating public subsidies for private schools—or, taking the opposite tack and fully subsidizing private schools, on the condition that they be open to all local students and do away with their student selection practices.13 These ideas merit further consideration and will be explored in a future publication.

Notes

- Conseil Supérieur De L’éducation, Remettre le cap sur l’équité, Rapport sur l’état et les besoins de l’éducation 2014-2016, Gouvernement du Québec, September 2016.,

- Anne-Marie Duclos And Philippe Hurteau, Inégalité scolaire : le Québec dernier de classe ?, socio-economic report, IRIS, September 2017.,

- École Ensemble, Plan pour un réseau scolaire commun, 2022.,

- Given the racial profiling and discrimination that racialized students in Quebec experience both inside and outside the school environment, one can assume that there is a racial component to this form of segregation as well. Commission Des Droits De La Personne Et Des Droits De La Jeunesse, Profilage racial et discrimination systémique des jeunes racisés, Rapport de la consultation sur le profilage racial et ses conséquences, 2011.,

- “Écoles privées,” Ministère de l’Éducation (MEQ), accessed June 6, 2022. It should be noted that this figure is disputed. The Fédération des établissements d’enseignement privés (FEEP) states that [Translation] “the amount of the government subsidy is 40% of the actual per student cost,” while a report by a committee of experts commissioned by the MEQ asserts that [Translation] “the actual amount of funding granted is closer to 75%.” “Foire aux questions,” FEEQ, accessed July 25, 2022; MEQ, Rapport du comité d’experts sur le financement, l’administration, la gestion et la gouvernance des commissions scolaires, May 2014, p. 128.,

- Conseil Supérieur De L’éducation, op. cit., p. 40.,

- Direction Des Encadrements Pédagogiques Et Scolaires, Collecte de données sur l’inventaire des projets pédagogiques particuliers, report to minister, MEQ, August 2020.,

- Ibid.,

- Conseil Supérieur De L’éducation, op. cit.; Duclos And Hurteau, op. cit.,

- Duclos And Hurteau, op. cit.,

- Conseil Supérieur De L’éducation, Les projets pédagogiques particuliers au secondaire : diversifier en toute équité, brief to the Minister of Education, Recreation and Sports, April 2007.,

- Direction Des Encadrements Pédagogiques Et Scolaires, op. cit.,

- Catherine Dubé, “Et si on coupait les vivres à l’école privée ?”, L’actualité, September 14, 2018; École Ensemble, op. cit.,