The public services, programs, and infrastructure that Canadians depend on every day cost money.

Hospitals and hospital staff cost money. Sending kids to school costs money. Building transit infrastructure costs money.

These are all good things. We have to pay for them.

In Canada, responsibility for the largest chunk of this spending falls to the provinces. Federal transfers help, but it is provincial legislatures that must raise most of the revenue they need.

Sadly, when it comes to raising revenue, Ontario has lagged behind other provinces for a long time.

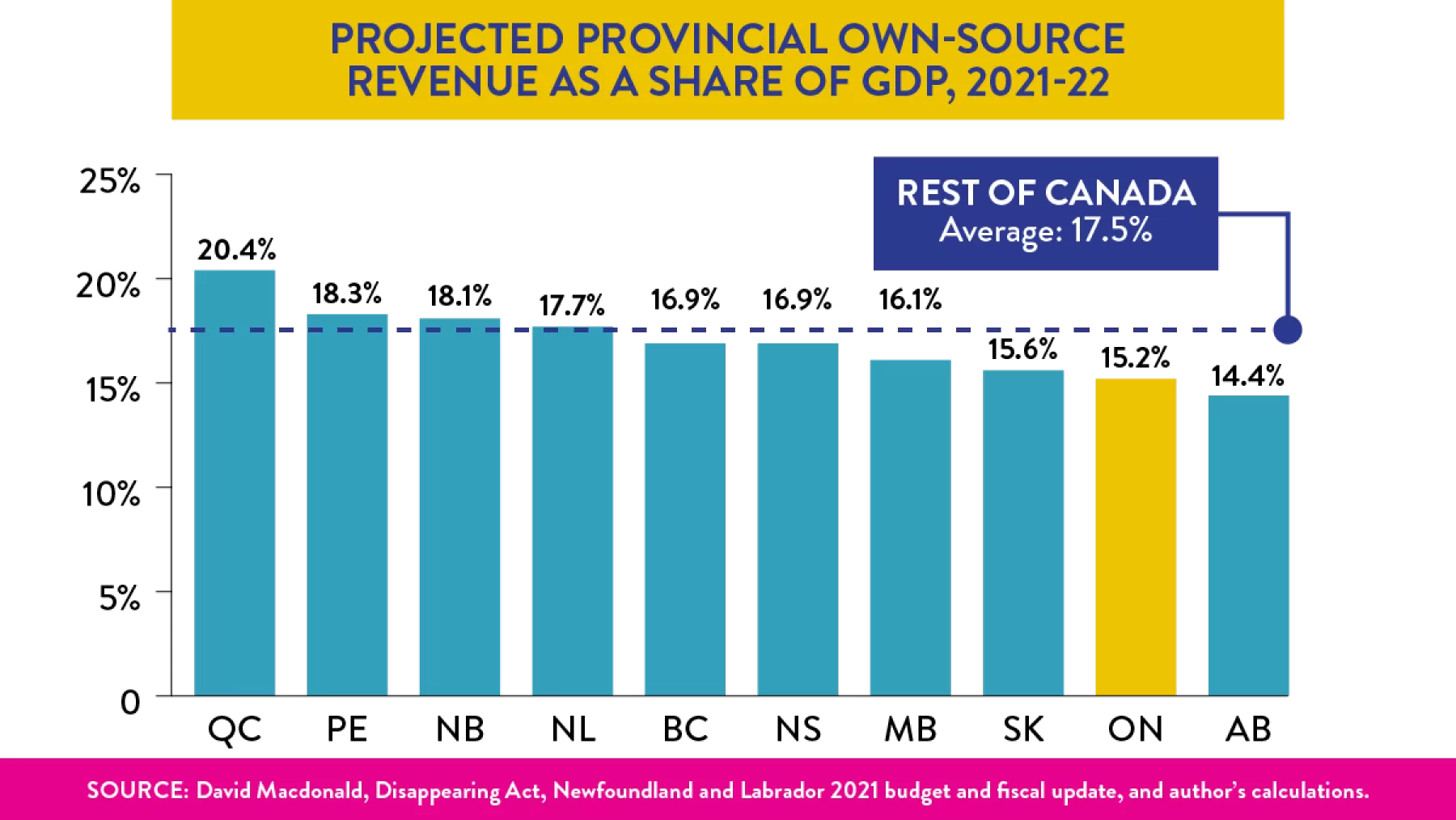

Economists use the term “fiscal effort” to assess how hard a given government is trying to raise revenue from its own sources. To compare provinces, “own-source” revenue is calculated as a percentage of each province’s total economic activity, also known as Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Based on the latest data, for the fiscal year just ending, Ontario ranked second-last of all provinces for fiscal effort.1 Queen’s Park’s own-source revenue will amount to 15.2% of GDP in 2021-22. The average for all other provinces will be 17.5%.

Why does that matter? It matters because if Ontario raised revenues for public programs at the same rate as the average province, that revenue would have been $22.6 billion higher.

It is hard to fathom a number this big, so a few comparisons may help. The provincial budget deficit this year will be roughly $12 billion. Ontario’s ongoing demand for more federal funding through the Canada Health Transfer calls for more than $10 billion a year. All told, the province’s total revenue for 2021-22 will be about $176 billion.

With $22.6 billion a year, Ontario could boost health care spending by that $10 billion, help two million school students bounce back from the two-year trauma of COVID-19, and still have $8 billion left over to tackle poverty, address the climate emergency, and boost wages for public employees currently barred by law from even trying to keep up to inflation.

That $22.6 billion would boost total provincial revenue by nearly 13%. It would breathe life into programs that have been gasping for air for more than a decade.

Unfortunately, just as Queen’s Park doesn’t like to raise revenue, it doesn’t like to pay for public services either.

The best measure of a province’s commitment to funding public programs is how much it spends per person. By this measure, Ontario spending is well below the average of the other provinces.

As the chart shows, Ontario would have to increase program spending by $1,623 per person, per year, just to be average. That means that right now, with 15 million Ontarians, the provincial government would have to spend an extra $24.3 billion just to be spending at the Canadian average for programs.

How much should Ontario collect in revenue to spend on public services?

Compared to other advanced economies, Canada is about average when it comes to raising revenue at all levels of government. But within Canada, compared to other provinces, Ontario is an outlier.

For at least a quarter of a century, Ontario politicians have peddled the notion that public services are too costly but tax cuts have no cost at all. This is untrue, as any exhausted health care worker or family in poverty can tell you.

Now, more than ever, Queen’s Park needs to make an effort to raise the revenue that will save our public services. To do so, let’s set an ambitious goal: that someday, not too long from now, we will meet the Canadian standard.

Let’s aim to be average.

For an overview of the post-pandemic finances of all provinces, please see Disappearing Act by CCPA senior economist David Macdonald.

1. These numbers are the most recent ones available. Last-place Alberta tabled its budget on Feb. 24, the day Russia invaded Ukraine. Rising revenue in that province as a result of higher oil prices since the war virtually guarantees Ontario will be in last place when updated Alberta figures are available.