New federal policies are being created and adapted daily to try and head off the worst-case economic impacts of COVID-19. Many of those modifications are in reaction to advocates pointing out pitfalls in the proposed design of emergency measures. As these programs unfold, I’ve been tracking how well they cover laid off workers who are bearing the economic brunt of the closure of complete sectors.

Between March 25th and April 6th—the space of only a week and a half—the Employment Insurance system is being re-tooled to deliver a Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)-equivalent that emulates most of the CERB conditions. For 84% of the workers who’ve been laid off in the past two weeks, the CERB and CERB-equivalent systems will provide a higher benefit rate than old EI. This will be a better deal for many workers, particularly lower wage ones with fewer hours.

The CERB may well be the foundation for a new, modern EI program if the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion has her way. But there are big issues as the EI and CERB programs try to co-exist which, left unaddressed, could mean hundreds of thousands of unemployed Canadians falling through the cracks.

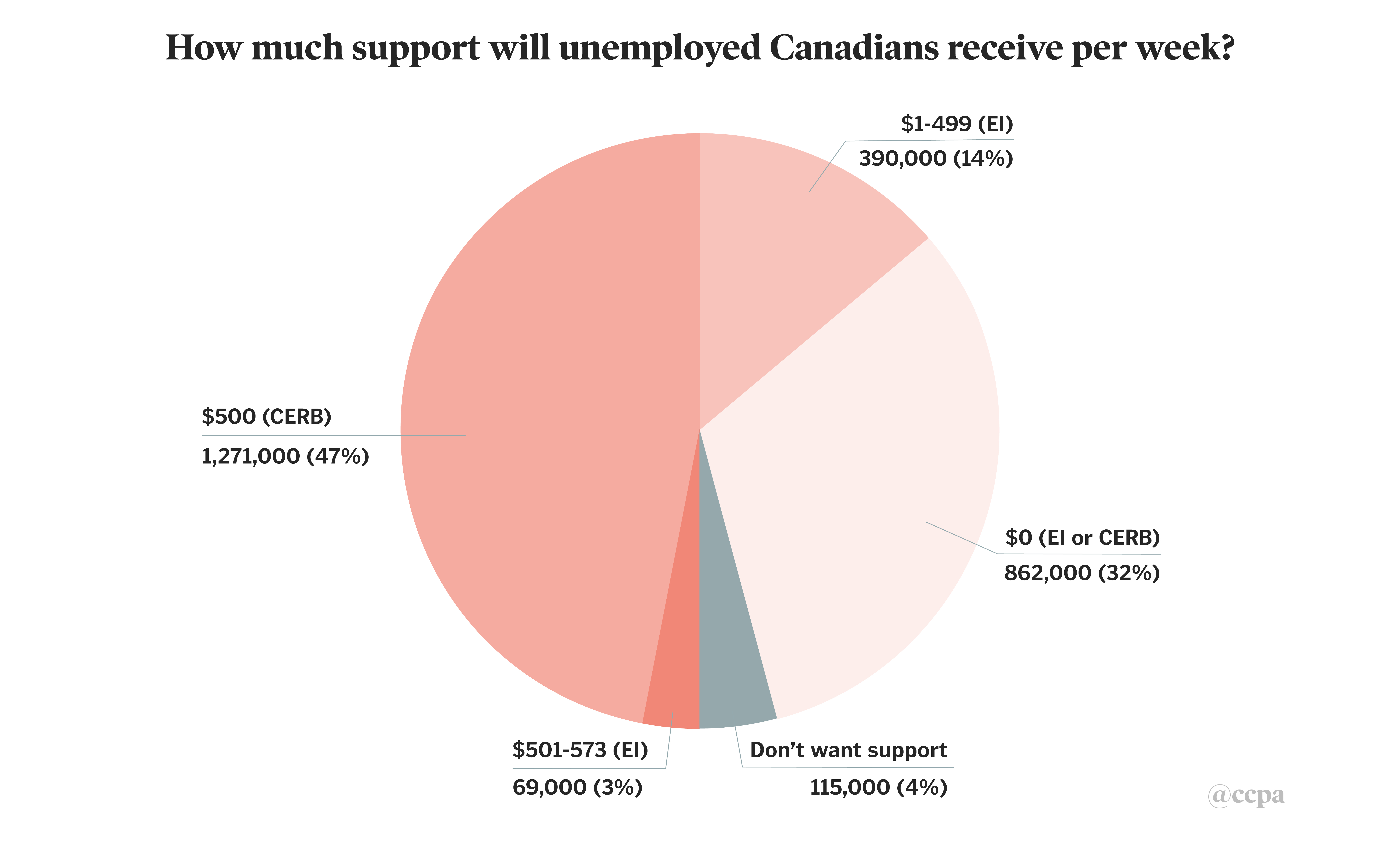

Those cracks are significant: a third of unemployed Canadians (862,000) receive nothing from either EI or CERB. Another 14% of unemployed people (390,000) will receive some support, but less than the $500 a week ($2,000 per four-week period), others will get under the CERB. Social Assistance recipients who work could also be forced to pay 100% of the CERB back to the province.

In this analysis, I’ll evaluate how much support unemployed Canadians will get from either EI benefits or the new CERB. This analysis makes extensive use of the February 2020 Public Use Microdata File (PUMF) and the 2018 EI Coverage Survey PUMF.

The CERB and EI: The ins and outs

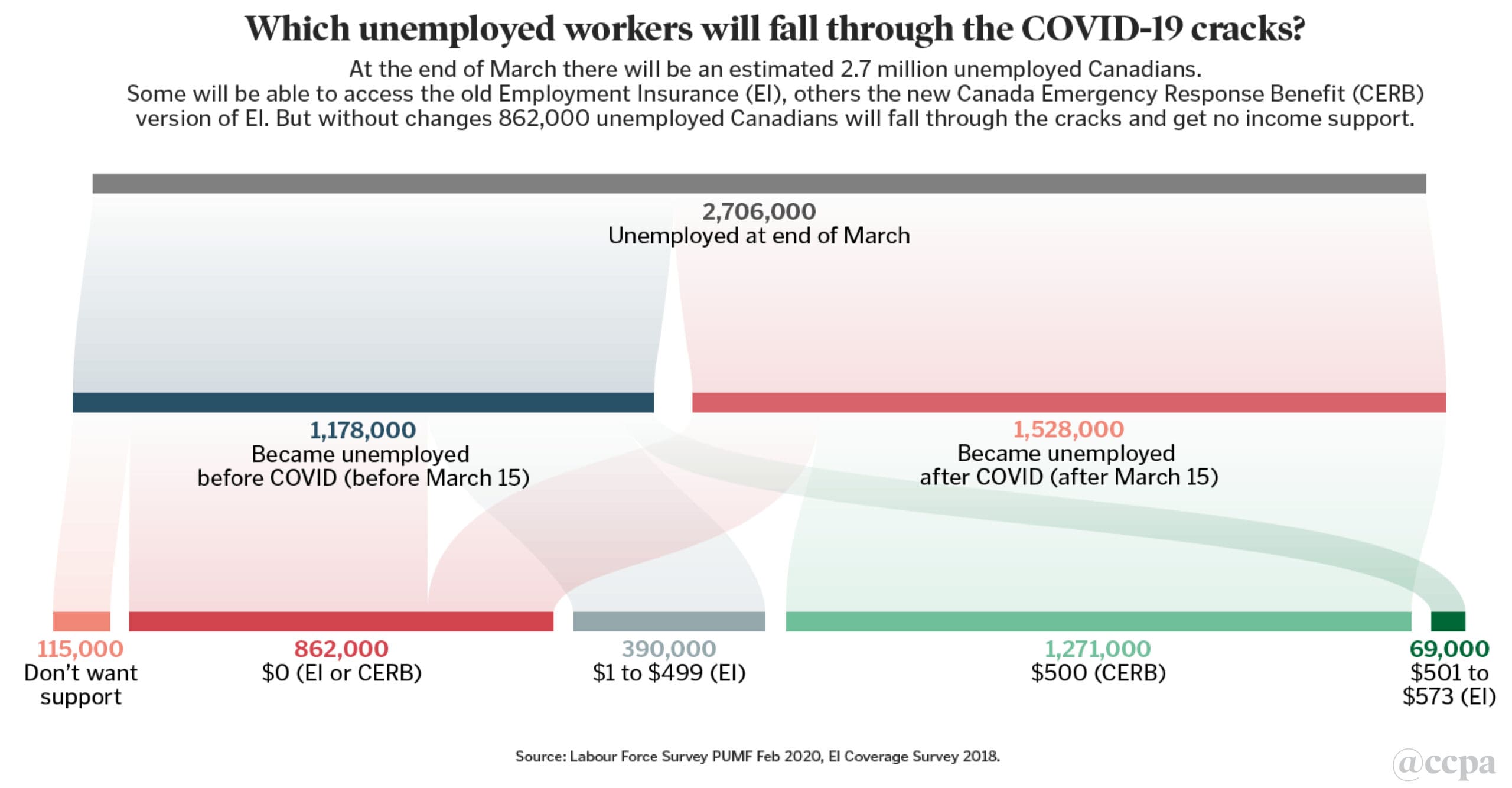

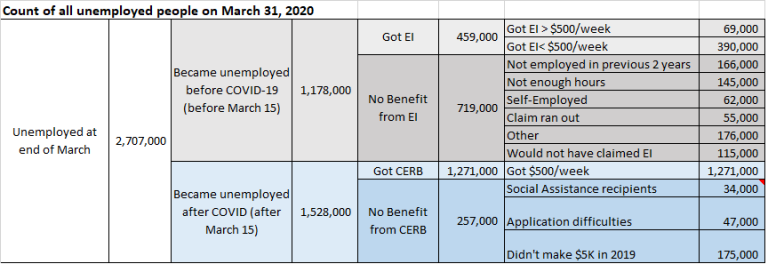

One of key requirements of the CERB is that you had to have ceased working because of COVID-19, which will include those who were laid off en-masse due to forced sector closure during the week of March 15 and afterwards. However, prior to March 15, there were still plenty of people looking for work—as of February 2020 our unemployment rate was 5.9%. At the end of February 2020, the 1.18 million Canadians who were already looking for work were joined by a further 1.53 million workers from the first round of COVID-19 layoffs in front line jobs in the shuttered sectors of retail (ex. grocery & drug stores), food/hospitality, arts/culture/sport and airlines. That means that by the end of March, we’ll likely have 2.7 million unemployed Canadians; 1.2 million from before COVID and another 1.5 million because of the virus, although these initial estimates will likely worsen over time.

Source: Labour Force Survey PUMF February 2020, EI Coverage survey PUMF 2018 and authors calculations

The 1.2 million Canadians who became unemployed before COVID-19 are not eligible for the CERB (which did not exist before March 15) – unless action is taken to provide some form of emergency benefits to this group. At the end of March, approximately 459,000 unemployed workers will likely be getting EI, and not the CERB, because they were already in the EI system prior to the EI application rush. EI only replaces 55% of earnings and has no floor, whereas the CERB provides a flat $2,000 for a four-week period (or $500 per week). As such, at the end of March there will be an estimated 390,000 workers receiving EI at less than the flat CERB rate of $500 a week. Another 69,000 unemployed workers receiving EI will be getting more than the CERB’s $500 a week.

EI coverage wasn’t particularly universal in the first place: of the 1.2 million unemployed Canadians who lost their jobs prior to COVID-19, an estimated 719,000 weren’t getting EI benefits. The most common reasons are that they were longer term unemployed (hadn’t worked in the last year), were self-employed (and not contributing to EI), were disqualified as ‘quit without just cause,’ were going to school, or had worked recently but without enough EI hours to qualify. (Of note: 115,000 of the unemployed who weren’t getting EI would have had no need to apply as they were receiving severance or were transitioning to retirement.)

604,000 of those who lost their jobs before COVID-19 can’t claim or do not qualify for EI. But they also do not qualify for the CERB because their layoff was before the virus. They will receive no income replacement benefit

Of the 1.5 million who have been laid off since March 15th, 1.3 million will likely get the CERB (with many receiving more generous compensation than what they would have received from the old EI system).

The CERB stipulates that a worker must have earned $5,000 in 2019 before ceasing work. This may seem like a low bar, but 175,000 workers in the sectors hit by the mass layoffs (food/hospitality, retail and arts/culture/sports) likely won’t meet the threshold. They’ll be unemployed but receive nothing from the CERB.

Social assistance recipients who were working (but lost their jobs due to COVID) will likely face a 100% clawback of any CERB payments unless provinces/territories agree to a change. If they get $2,000 from the CERB, their social assistance transfers will fall by $2,000 (many don’t even get that much). In other words, they’ll see no benefit. There will be an estimated 34,000 people in this group.

The CERB is an application-based program, meaning if you don’t go to the right website and fill everything in correctly, you don’t get the benefit. In 2018, 3% of all unemployed people didn’t apply for EI because they didn’t know about it. Given how rapidly CERB has been developed, we can assume at least 3% of the people who might be eligible for it won’t apply out of a lack of knowledge. This is likely a modest estimate: applicants will require reliable access to the internet and familiarity with computer-based applications. Libraries and government offices that normally assist the most vulnerable are shuttered during the crisis and people can’t get someone to help in their homes due to physical distancing. Although phone applications are an option, normally understaffed government call centres are now completely overwhelmed; lengthy wait times are likely to further discourage applicants. This will mean at least another 47,000 laid off workers who won’t get CERB because they don’t know about it even if they’d likely qualify.

All told, approximately 257,000 people who became unemployed after March 15th won’t see any benefit from the CERB (or the CERB-equivalent benefit through EI). And by the end of March, there will be a total of 862,000 unemployed Canadians—a third of all unemployed people—receiving no income support through EI or CERB for the reasons above. Another 390,000 unemployed Canadians (14%) will be receiving EI, but it will be for less than the flat $500 a week that CERB provides.

Two other groups who aren’t modelled here but are technically included in the above figures are temporary foreign workers (TFWs) and undocumented workers. Undocumented workers could easily have been caught up in the mass layoffs of the last two weeks of March. There is presently no clear avenue for them to access CERB despite a large drop in income.

TFWs have EI deducted from each paycheque but may not meet the residency rules for either EI or the CERB. Due to COVID-19 health-related measures, they have to be quarantined for 14 days upon arriving, presumably without pay. This 14-day period is also the minimum threshold of non-pay required by the CERB. TFWs who work in retail, food and accommodations were possibly laid off over the past two weeks; however, most TFWs are employed in agricultural or child care where they are much less likely to have been laid off, but would still face mandatory quarantine upon arrival. It’s not clear at this point if they will qualify for any emergency benefit.

All of the above analysis also overlooks high school and university or college students for whom summer jobs will be virtually non-existent. Those students can’t gain access to the CERB as their employment hasn’t ceased due to COVID-19; it just hasn’t started.

Recommendations

Critical changes can and should still be made to the CERB which would allow all unemployed people to receive the benefit, no matter when they lost their jobs or how much they made in the past year. Topping up all present EI recipients to the CERB payment of $500 per week would further equalize the situation. Finally, coordinating with the provinces so the CERB isn’t clawed back dollar for dollar from social assistance would provide much-needed assistance to those most vulnerable.

The federal government has moved rapidly to stem the worst economic impacts of this crisis and it has shown itself very willing to adjust its programs as the situation unfolds. Now is the time to continue to tweak these programs to ensure that no unemployed Canadians are left without secure and adequate income support.

Table 1: Estimated count of unemployed Canadians, March 31, 2020

The author would like to thank Laurell Ritchie for her comments on an earlier version of this analysis.

A previous version of this post included a typo noting the CERB rate was $500/month. It has been corrected to reflect the correct amount of $500/week.