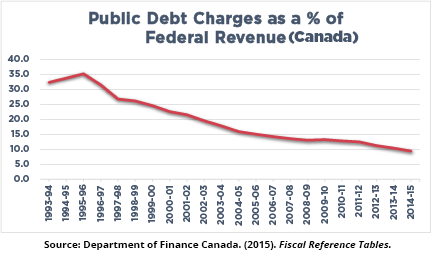

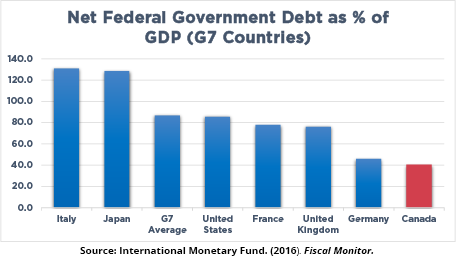

Days after the 2015 federal election, a Globe and Mail opinion piece pointed out something many anti-poverty advocates already knew: “Every province and territory but British Columbia has a poverty reduction strategy in place or in development. Many cities and towns do, too. Until now, the big missing piece has been our national government.” This was timely, as the Trudeau Liberals had just promised such a strategy in their election platform. More recently, the mandate letter for Canada’s Minister of Families, Children and Social Development charged the Honourable Jean-Yves Duclos with the task of leading this effort.With that in mind, here are 10 things to know about poverty as it relates to Canada’s federal government.1. Public social spending in Canada is considerably lower than the average for other member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Indeed, total public social spending in Canada represents about 17% of our Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By contrast, the OECD average is almost 22%. (You can see these figures for yourself here.) Every 1% of GDP translates into approximately $560 per Canadian per year. Public social expenditure includes spending on social housing and social assistance (i.e. welfare, disability benefits). A full list of items included in these OECD figures can be found here.2. Our current federal government has already taken several important initiatives pertaining to poverty reduction. In creating the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), the federal government increased federal spending on child benefits, making them more generous than previously for low- and middle-income households (but less generous for higher-income households). The CCB has reduced child poverty, though not as much as the current federal government once claimed. What’s more, the Guaranteed Income Supplement ‘top up’ for single seniors will lift an estimated 37,000 Canadians out of poverty; David Macdonald has blogged about this here. Further, expanding the Canada Pension Plan and returning the age of eligibility for Old Age Security to 65 will both reduce the number of seniors living in poverty. (The federal government has also made important announcements pertaining to new funding for affordable housing and homelessness; these initiatives will be discussed in point #9 below.)3. More public investment (including on affordable housing and child care) could create jobs and reduce poverty even further. A recent report by the Centre for the Study of Living Standards recommends that federal, provincial and territorial governments take advantage of low interest rates to make public investments. It notes: “Running deficits need not be inconsistent with a goal of not raising the debt to GDP ratio, provided that the deficits are small enough that the debt does not grow faster than GDP. Temporarily running larger deficits to fund valuable public investments while stimulating the economy during periods of poor economic performance are justifiable (p. xii).” This advice has been echoed by Bank of Canada Governor, Stephen Poloz. What’s more, even former Prime Minister Paul Martin has recently argued for the need to continue having public deficits at the present juncture. Along these lines, the Trudeau government has already announced important public investments (however, their decision to finance such investments via expensive private borrowing has been called into question both here and here).4. Canada’s federal government could do a better job of redistributing income, which in turn could reduce poverty even more. Three recent reports (all published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives) make a strong case for better redistribution of income via Canada’s tax system. An October 2015 report by Lars Osberg makes a strong case in favour of tax increases for Canadians making $200,000 annually or more. A November 2015 report by Jordan Brennan argues persuasively in favour of increasing corporate income taxes. Finally, a December 2016 report by David Macdonald argues that Canada’s current tax expenditure system disproportionately benefits higher-income earners, and that a reformed system could change that.5. A National Framework on Early Learning and Child Care could reduce poverty. The federal government has already announced $500 million “to support the establishment of a National Framework on Early Learning and Child Care.” Such a framework is now being developed in partnership with provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments. The Child Care Advocacy Association of Canada has weighed in with its demands in this respect here. In addition to helping children, child care can also have immediate results on a government’s bottom line—indeed, research from Quebec makes clear that a well-funded child care program can pay for itself (i.e., more parents enter the labour force and the taxes they pay increase government revenue more than enough for the government to finance the cost of the child care). For a fulsome discussion of this phenomenon in Quebec, see this 2012 report; for a shorter analysis, see this December 2016 opinion piece by Pierre Fortin.6. Expanding the Working Income Tax Benefit—a measure that has appeal on both the left and right of the political spectrum—could reduce poverty. The Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB) was introduced in 2007 by Canada’s federal government. A refundable tax credit, it’s intended to make precarious work more attractive to workers. This December 2016 analysis by Rob Gillezeau and Sean Speer notes “there is actually a broad political consensus” nationally in favour of expanding WITB. People and groups on the left of the political spectrum generally like it because it transfers more money into the hands of low-income households; and people on the right tend to like it because it increases labour market participation. Gillezeau and Speer note: “How broad is the cross-party Canadian consensus on the WITB? In a 2013 report on income inequality presented by the Standing Committee on Finance, the three major parties called for a further expansion to the program.” There are other more recent examples of such cross-partisan support. The federal NDP’s 2015 platform proposed a 15% increase in WITB’s value. In June 2016, the Trudeau government announced a $250 million increase to the WITB to offset increased contributions being made by low-income workers in light of the expanded Canada Pension Plan. And in November 2016, Conservative Party leadership candidate Michael Chong proposed that the WITB be doubled.7. A national pharmacare program could both: a) help a lot of people in poverty afford prescription medication, and b) prevent people with low incomes and health problems from falling into poverty. A recent study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal argues that a universal pharmacare system would cost governments an extra $1 billion annually…yet, it would save Canadian households collectively approximately $7 billion annually. A big reason for this differential is that a nationally-administered drug plan can take advantage of the buying power of one large body to negotiate lower prices from pharmaceutical companies. In November 2015, more than 300 health professionals and academics wrote an open letter to Prime Minister Trudeau, calling for such a plan—they also note that almost 90% of Canadians support adding prescription medication to Canadian medicare. 8. Canada’s public debt is low. Combined with low interest rates (discussed in point #3 above) this means we have ample opportunity to spend more on social programs that can reduce poverty. Our federal government’s annual public debt charges (expressed as a % of federal revenue) have decreased from 35% to 10% since the mid-1990s. In fact, Canada’s federal government has the lowest net government debt of any G7 country.

8. Canada’s public debt is low. Combined with low interest rates (discussed in point #3 above) this means we have ample opportunity to spend more on social programs that can reduce poverty. Our federal government’s annual public debt charges (expressed as a % of federal revenue) have decreased from 35% to 10% since the mid-1990s. In fact, Canada’s federal government has the lowest net government debt of any G7 country. 9. A well-funded national housing strategy could help reduce poverty. Canada has much less social housing (per capita) than the rest of the OECD. That said, the Trudeau government’s first budget announced substantial new funding for housing and homelessness. Initiatives included: new investments for housing for First Nations, Inuit and Northern communities (approx. $370M annually for two years); the doubling of annual funding for the Investment in Affordable Housing Initiative (for 2016/17 and 2016/18 only); $100 million in new annual funding for seniors housing (also for two years); new funding for renovations of existing social housing; and $55 million in new annual funding for the Homelessness Partnering Strategy, also for two years.[1] (For more on the need for Canada to develop a national housing strategy, see this September 2016 blog post.)10. Any poverty reduction effort by the federal government should be done in partnership with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. It is abundantly clear from the data that Indigenous peoples face a considerable degree of poverty. The federal government must remain cognizant of the historical impacts of colonization and the residual impact of race-based policies on this subpopulation group. This has been underlined by contemporary reports, including the final report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the more recent Truth and Reconciliation Report. In particular, substantial investments should be made towards both on-reserve housing and housing for urban Aboriginal peoples. What’s more, the federal government should direct Indigenous Affairs and Northern Development Canada to consult on a Nation to Nation basis in discussing the details. To read the Assembly of First Nations’ policy recommendations going into the 2015 federal election campaign, see this report.

9. A well-funded national housing strategy could help reduce poverty. Canada has much less social housing (per capita) than the rest of the OECD. That said, the Trudeau government’s first budget announced substantial new funding for housing and homelessness. Initiatives included: new investments for housing for First Nations, Inuit and Northern communities (approx. $370M annually for two years); the doubling of annual funding for the Investment in Affordable Housing Initiative (for 2016/17 and 2016/18 only); $100 million in new annual funding for seniors housing (also for two years); new funding for renovations of existing social housing; and $55 million in new annual funding for the Homelessness Partnering Strategy, also for two years.[1] (For more on the need for Canada to develop a national housing strategy, see this September 2016 blog post.)10. Any poverty reduction effort by the federal government should be done in partnership with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. It is abundantly clear from the data that Indigenous peoples face a considerable degree of poverty. The federal government must remain cognizant of the historical impacts of colonization and the residual impact of race-based policies on this subpopulation group. This has been underlined by contemporary reports, including the final report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the more recent Truth and Reconciliation Report. In particular, substantial investments should be made towards both on-reserve housing and housing for urban Aboriginal peoples. What’s more, the federal government should direct Indigenous Affairs and Northern Development Canada to consult on a Nation to Nation basis in discussing the details. To read the Assembly of First Nations’ policy recommendations going into the 2015 federal election campaign, see this report.

Nick Falvo Ph.D, is the Director of Research and Data at the Calgary Homeless Foundation (CHF). Janice Chan is a System Planner at CHF. Chidom Otogwu is a HMIS Specialist at CHF.The authors wish to thank the following individuals for invaluable assistance with this blog post: Jordan Brennan, Gerald Chipeur, Angela Daley, Louise Gallagher, Rob Gillezeau, Ron Kneebone, Kara Layher, David Macdonald, Angella MacEwen, Michael Mendelson, Kevin Milligan, Allan Moscovitch, Robin Shaban, Richard Shillington, Joel Sinclair, Jim Stanford, John Stapleton, Kaylie Tiessen and Seth Klein. Any errors lie with the authors.This post originally appeared on the Calgary Homeless Foundation blog.[1] A succinct list of housing-related initiatives from the 2016/17 federal budget can be found here, while a more thorough analysis can be found here.