Months after the October 7, 2023 attacks by Hamas fighters on Israelis, and the ensuing and ongoing bombardment of Gaza by Israeli Defence Forces that continue to kill thousands of Palestinians, the war and its underlying historical and political context is a simmering daily reality in Canadian schools, especially where students’ families have ties to either side.

According to pollster Nik Nanos,“ The conflict has created tension across the country that is being felt in our communities.” Seven in 10 Canadians are concerned (39 per cent) or somewhat concerned (30 per cent) that there will be an increase in hate-motivated incidents in our communities resulting from the conflict in the Middle East according to his recent opinion research (Nanos, 2023).

Schools reflect and are visited by the political and social forces that shape the broader society. Since October 7th, incidents of reported racism directed at the Palestinian and Jewish communities have spiked, according to the Toronto District School Board.

The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario called on school boards to ensure those affected are supported and safe. “The conflict will undoubtedly affect the sense of safety and well-being of many students and staff members, some of whom have family members in Israel and Palestine,” ETFO said in an October 10 statement (Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2023).

But direction from the Ministry, Boards and administrators has been of little help, and may be making matters worse in some cases.

For instance, the Toronto District School Board reversed its policy of informing parents by letter of hate incidents at schools in a measure to lessen their impact. But several parents were “disheartened” to learn from their children that swastikas were spray painted on school property, rather than normally being notified by school officials over email. A board spokesperson explained these reports may result in further harm to students and the overall school climate, and communication about such incidents prompted copycat incidents (“Toronto school board,” 2024).

“There’s been a lack of information and nothing has come out [from the Ministry] pedagogically and policy-speaking,” said Dr. Vidya Shah, Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at York University. Educators have been left largely on their own to navigate angry parents, activist groups, and wary children, sometimes resulting in confusion and frustration in a school system that is reaching the boiling point.

Teachers are trying their best to create a safe space for pupils. “At this point in the year I’m pretty connected with them as individuals and I check in with them one on one if I see that they seem disconnected from school in any way,” a Grade 8 Toronto public school teacher, who wished to remain anonymous, told me in late October. “I think most of us are just letting students know that we are here for them if they need to talk.”

But troubling incidents have persisted. In October a principal of an Ottawa public school apologized for asking an elementary school student to remove the Palestinian flag as their profile picture during an online class (Williams, 2023).

A video of the incident reported on by CBC recorded the principal saying to the student, “We will follow up with your family because we want to keep all students feeling safe, welcome and included in our classrooms.” The student replied, “You’re not really welcoming me right now.” Two other students changed their photos to Palestinian flags as well.

A statement from the school board following the incident said, “While this was regrettable, we would ask for understanding as school staff are working to navigate an extremely challenging international situation in a way that allows all students and staff to feel safe and supported.”

The circumstances and media coverage surrounding what was likely a well-intentioned principal acting in a policy vacuum will no doubt give pause to other educators trying to address the conflict in classroom settings.

The public school teacher in Toronto I spoke with said, “We had a quick staff meeting a couple weeks stating that we need to be aware and sensitive to the fact that many of our students and their families are being impacted emotionally by what is happening. We have quite a number of Palestinian students. We are allowed to speak of the war and what’s happening if we feel comfortable and are informed enough.”

But will teachers feel comfortable and informed enough to broach the subject with students, with so much scrutiny focused on teachers by parents, activists and the media? Are there more risks than benefits?

Sadly, in the absence of sufficient guidance and support, it’s perhaps unsurprising that teachers may prefer to avoid handling controversial topics altogether.

Dr. Sharon Anne Cook, Professor Emerita and Distinguished University Professor at the University of Ottawa, points out in her reflections on a career as a peace educator working with pre-service teachers, that early career teachers face plenty of barriers. “They feared that they would emphasize the wrong sources of conflict in this welter of detail… they were unpracticed in unsnarling the cultural origins of conflict and worried about hurting the feelings of participating students,” she writes (Cook, 2014).

In November, the Ontario Ministry of Education announced new and expanded mandatory learning about the Holocaust in the compulsory Grade 10 History course and partnerships with Jewish organizations. Last year the province announced an expansion of its plan to combat Islamophobia in schools with province-wide guides, resources, materials and Muslim community partnerships to counter Islamophobic narratives in culture, online, and in the classroom.

Still, the Ministry has not done enough to avoid some teachers and schools refusing to deal with the subject, which has allowed frustration to grow. In some jurisdictions the topic is seen as either an issue requiring conflict-resolution or anti-bullying tactics. In other contexts the conflict is dealt with as a mental health matter where counseling services are provided to help affected students. But treating the thousands of deaths, in some cases of students’ family members, as bullying or mental health falls well short of the demands of students.

What is the role of peace education in schools?

The schools administration’s reluctance to address the issue in school is a missed opportunity to help students grapple with the roots of conflict, and ways to promote peace in this, and other contexts.

Peace education employs a range of pedagogical approaches. In early grade-levels, peace education might focus on the personal safety of students, such as anti-bullying strategies in school-yards. In later grade-levels, peace education might incorporate conflict-resolution.

Influential peace education scholar, the late Betty Reardon, did not limit the goal of peace education to “understanding each other” or “nonviolent person behavior,” but was very clear that the social purpose of peace education is to eliminate social injustice, renounce violence, and abolish war, which connect the political and interpersonal dimension (Winterstein, 2013).

Like Reardon, peace education expert Dr. Kathy Bickmore at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education is critical of the manner in which conflict-resolution is sometimes taught, considering it better described as “conflict-avoidance.”

Bickmore, who prefers the term peacebuilding, says peacebuilding education is “defined by peace studies theorists as overcoming structural violence (exploitation, repression, marginalization) and cultural violence (subconscious beliefs or assumptions supporting violence).” It should include themes of harmony-building and communication, individual skill-building such as critical reasoning, and political, international and social conflict (Bickmore, 2005).

In her study of curricula from several Canadian provinces, Bickmore identified three thematic groupings:

Harmony-building:

1. Interpersonal contribution, responsibility, communication and cooperation

2. Appreciation of diverse heritages and viewpoints, multiculturalism, national unity

Individual skill-building:

3. Conflict resolution: managing disputes and avoiding violence

4. Critical reasoning and problem solving skills

Political, international and social conflict:

5. Citizen participation, governance and (Canadian) ideals

6. Global interdependence: peace, human rights, and ecology

7. Social conflict issues (past or present conflicts or public controversies

To contribute to democratic peacebuilding, explicit curriculum would have to delve into the ‘unsafe but real’ world of social and political conflicts that defy simple negotiated settlement, including the roots and human costs of current local and global injustices, says Bickmore.

And what of the teacher’s own values when teaching peace education? Are they expected to be set aside and the teacher adopts the role of a neutral facilitator of learning?

Kathy Bickmore says, “Given the violent state of the world, presumably no peacebuilding citizenship educator pretends objectivity — we seek to reduce and transform violence and social exclusion.”

But Vidya Shah argues that teachers are caught between the expectations of the school system and their own reaction to the terrible conflict in Gaza. “Individual teachers have to speak out because of this internal struggle,” she says. And without support, some fear losing their jobs.

Parents and students want schools to do more

Parent groups on both sides of the conflict are pressuring school boards to do more for students. In October pro-Palestinian parents accused the Toronto District School Board of not doing enough to protect students from anti-Palestinian racism. In response, a TDSB spokesperson said the school board focuses on mental health and wellbeing of students, and takes steps to prevent any form of hate “such as antisemitism or islamophobia in our classrooms” (“Jewish, Palestinian parents,” 2023).

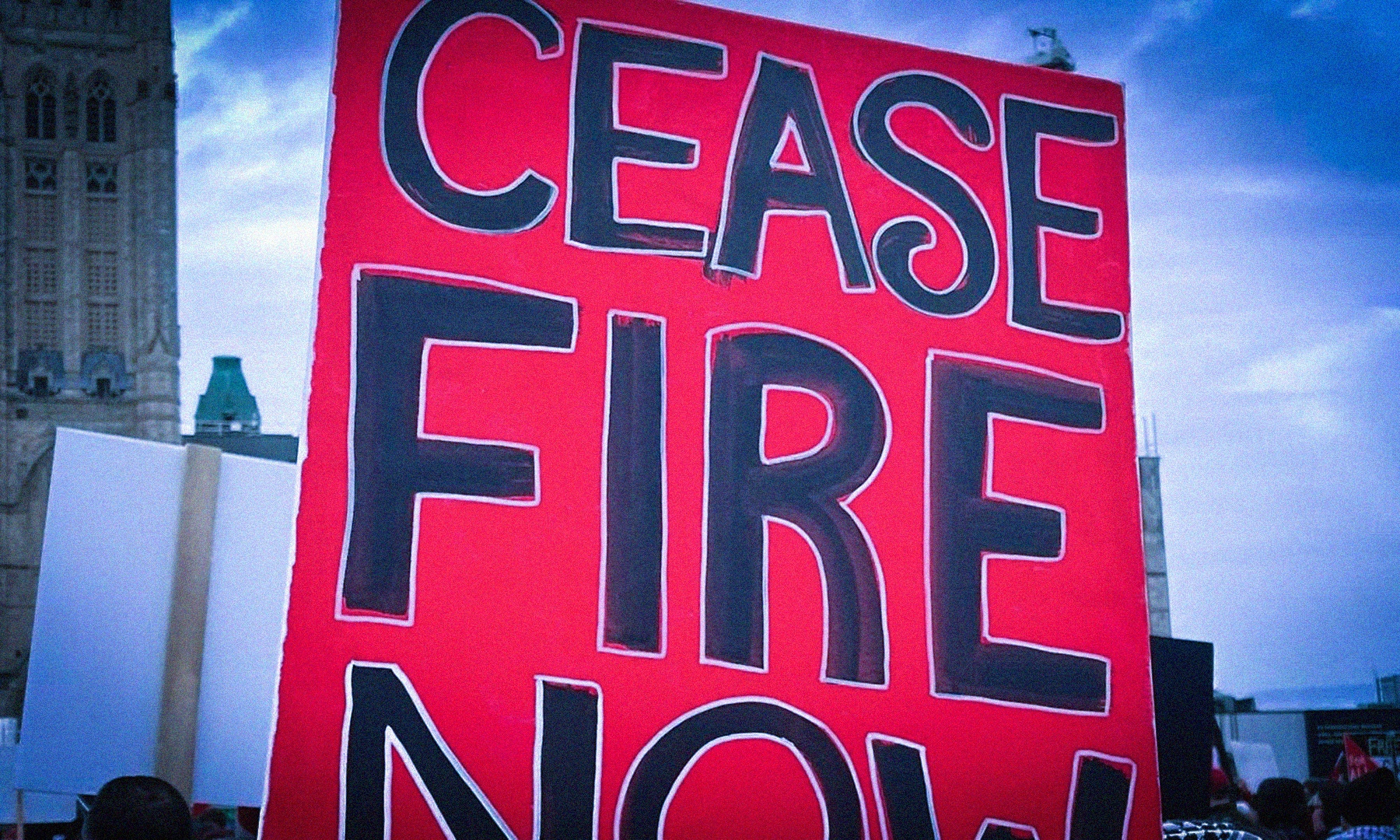

These measures were insufficient to avoid a walkout by students in November while the death toll in Gaza skyrocketed as a result of the punishing Israeli bombings. Ceasefire Now, describing itself as a loose coalition of 42 high school groups in Ontario, posted a list of demands that included a ceasefire and that “Ontario schools protect Palestinian students, create safe spaces for them, and refrain from censoring and punishing solidarity with Palestine” (Muslim Link, 2023).

While the Ontario Ministry of Education has demonstrated a clear commitment through curriculum changes to teach the Holocaust and address anti-Jewish racism, some have pointed to a lack of equity of approach, where many will be caught between their own personal internal struggles and conflict avoidance.

Dr. Shah is frustrated with what she described as repression of pro-Palestinian voices and views. “I have never seen it to this degree,” she said, pointing to several cases of teachers and principals being sanctioned for speaking out on social media against Israel and in support of Palestinians. She says authorities need to, “stop criminalizing resistance and stop policing language so people can speak their conscience without fear of losing their jobs.”

Ontario’s Education Minister Stephen Lecce said following the October 7 attack he warned all school boards the government did not want “personal perspectives” brought to the classroom. “I think fundamentally the ministry’s role is to make sure we build the capacity and confidence of teachers to be allies in rooting out this hate,” he said.

Dr. Bickmore says it’s very challenging for schools to strike the right balance when handling such complex events, but it’s not impossible. “Teachers get blamed when things go badly, but they often don’t get a whole lot of support to do things well” (“Jewish, Palestinian parents,” 2023).