Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

The Ontario Conservatives’ first budget is being delivered on Thursday. Normally this is the first opportunity for the public to compare the government’s plan with any promises the governing party made trying to get elected. In this case, since there was no Conservative campaign platform, and the Ford government has coasted along without outlining exactly what programs they’ll fund and which they’ll cut, Thursday is likely to hold a few surprises.

On the child care front, it appears that some sort of tax credit, similar to the Brown proposal, is set to drop. Since we don’t yet know the details of this new plan, I’ll stick with the Brown plan and provide updates after budget day. Briefly, the Brown plan would refund a family, at most, $6,750 of fees paid in a year—if you spent over $9,000 that year on child care but earned $35,000 or less a year. Parents who make more get less back, again at least under the Brown plan.

Now, I’m a spreadsheet guy and this was confusing to me. The following assessment of the Brown plan therefore uses what parents actually paid out of pocket for child care last year, after tax credits, based on real fees in 2018. This will avoid any fairy tale values pulled out of thin air. The result: parents, even those with low incomes, don’t do all that well under Brown plan for Conservative child care policy, which may or may not be what we see in the budget.

Is this tax credit really for low income families?

The short answer is no. Hypothetically, you get the maximum amount if you make $35,000 or less in a year, but it doesn’t really matter, because no modest income family could afford to pay the fees and then wait until tax time for the credit. The tax credit is competing against the existing program of subsidies for low income families, and Ontario’s subsidy is the most generous in Canada.

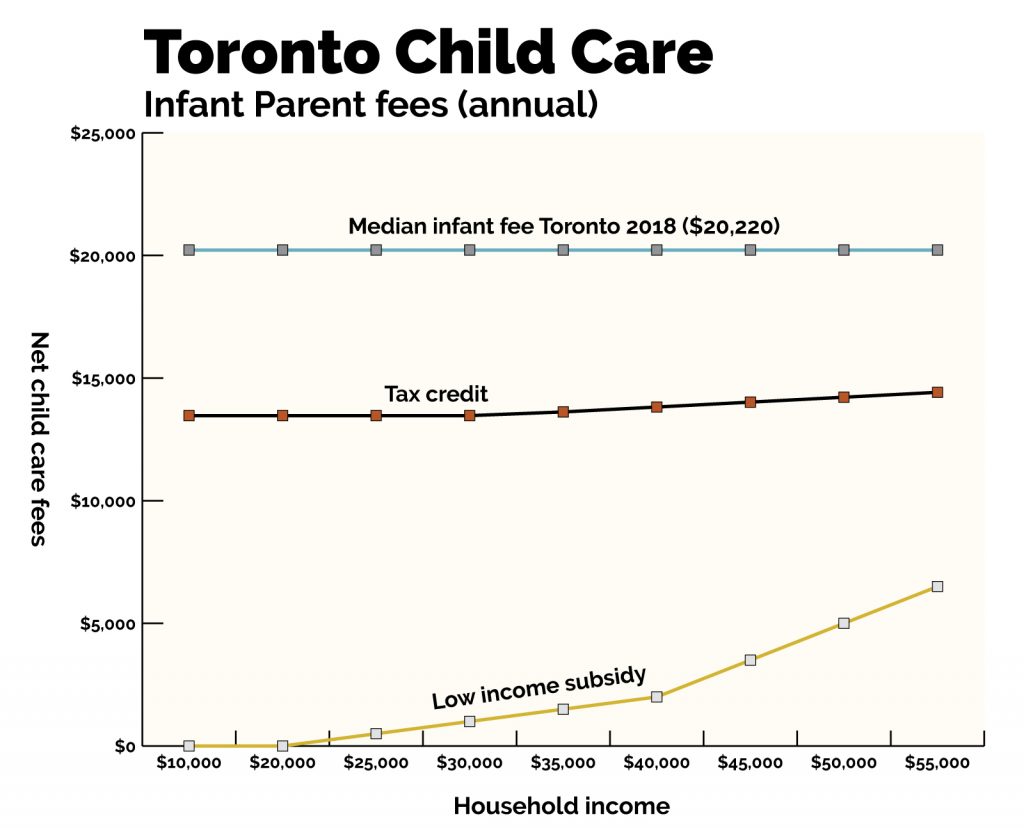

Figure 1 shows the situation in Toronto, where median infant fees are $1,685 a month, or $20,220 a year. Mathematically, a family making $35,000 could spend two-thirds of its income on child care alone and then get $6,750 back at tax time, but this would be crazy. You still have to feed and house your children. Even after the rebate, the net cost of child care is $13,470, still a third of your income.

What a family making $35,000 is actually going to do is apply for a low income subsidy. With the subsidy their out-of-pocket cost for their Toronto spot is just $125 a month, or $1,500 a year. So if you make $35,000 a year, you’re clearly going to try for a low income spot, and if you don’t get it you’re just not going to use child care, credit or not.

Figure 1: Toronto infant parental fees, tax credit, low income subsidy (annual)

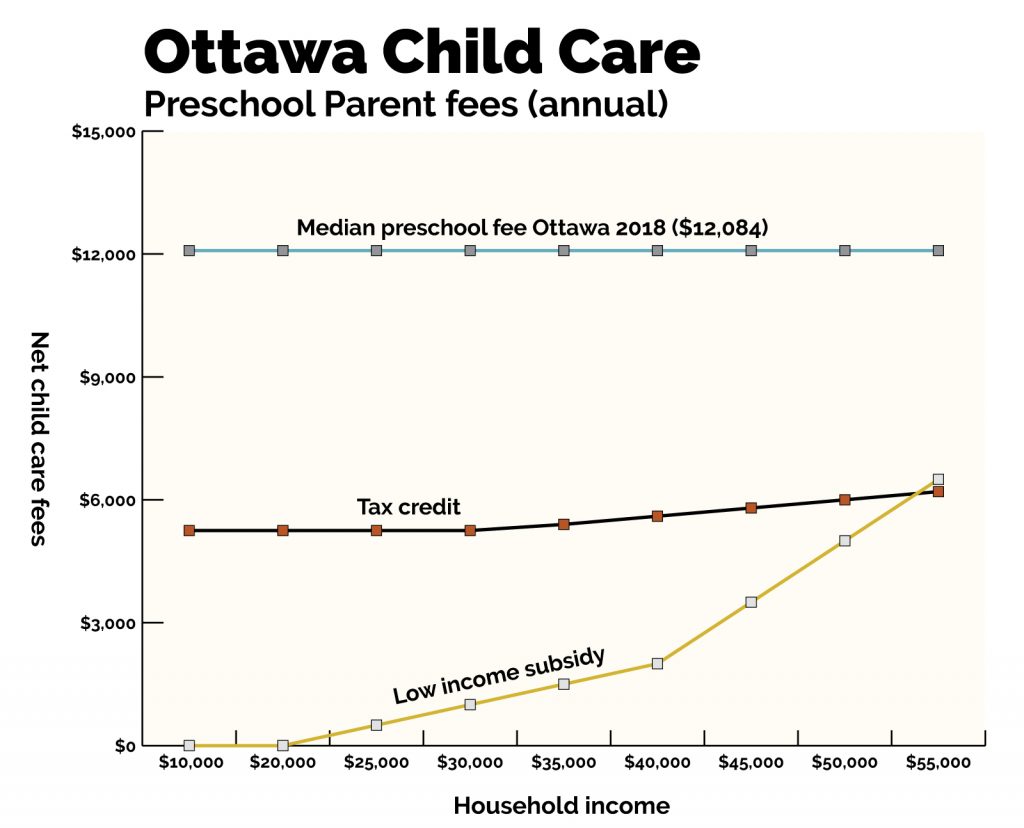

Now, Toronto infant fees are the highest of any fees in the country; commonly it will cost around $1,000 a month for a licensed preschool space. In Ottawa, the fee for a median preschool space is $1,007 a month, or $12,084 a year. Figure 2 runs the same calculations as Figure 1, but at Ottawa’s lower fee level. Even in this scenario, families making $35,000 or less will still seek out a subsidized space, which is far cheaper ($125 a month, or $1,500 a year).

While the new program may be pitched as a low income aid, no low income family would ever use the full value, since fees are just too high: they’d go for a subsidy or avoid the system altogether. The low income portion of this credit isn’t for low income families. It might as well be for unicorns.

Figure 2: Ottawa preschool parental fees, tax credit, low income subsidy (annual)

Have large child care tax credits been tried elsewhere?

Quebec has a growing for-profit child care system financed by exactly the type of tax credit proposed in the Brown plan/maybe Ford plan. In most of Quebec’s big cities about a third of spaces are not within the vaunted $8/day system, but are rather at market rates against which the tax credit is applied.

It is an interesting controlled experiment to see which system provides better outcomes, the public capped fee or the for-private market rate. Even taking the tax credit into account, the for-profit system ends up being more expensive for parents. Moreover, quality is lower in that for-profit system, which I suppose shouldn’t be that surprising: you have to generate those profits somehow, often by compromising on quality.

Will tax credits reduce wait lists?

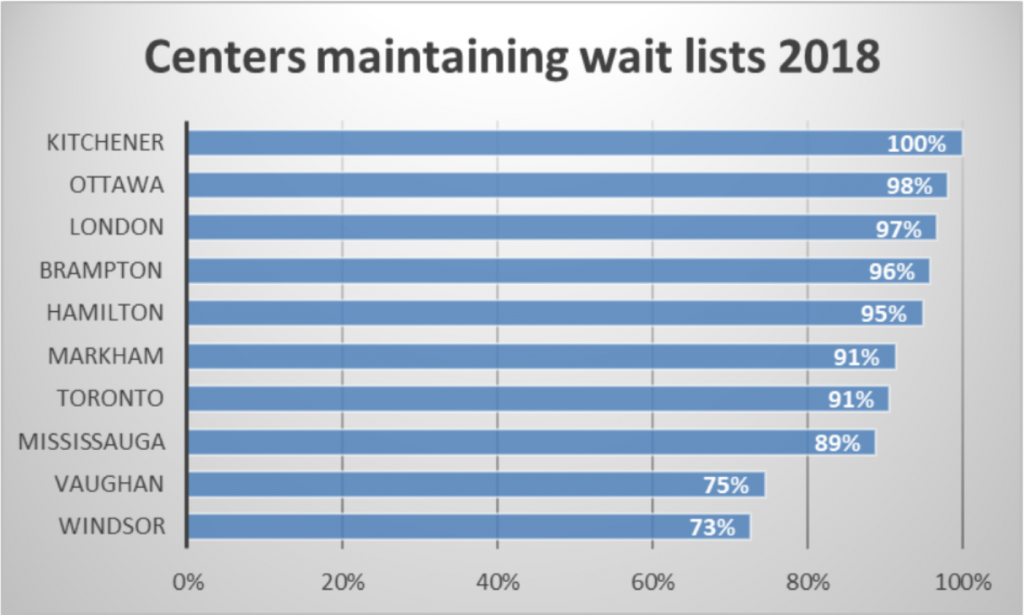

Tax credits don’t build quality child care spaces. They also don’t reduce wait lists. In the larger Ontario cities, wait lists are essentially universal at all child care centres. Given that places like Toronto are already the most expensive cities in the country for child care, just having higher fees for spaces does not mean you’ll have fewer or shorter waiting lists.

The market, left to its own devices, will not build enough spaces. Only public policy does that. If anything, a new tax credit program in Ontario will merely push up demand, making wait lists even longer.

Proposed tax credits won’t fill the gap

There are not nearly enough spaces as it stands in Ontario, which ranks 8th out of 13 provinces and territories in this respect. Ontario has three non-school-aged kids vying for every licensed space. Several Some Ontario cities do even worse than the average. In Brampton, 95% of children live in a child care desert (a postal code with more than three kids per licensed space). Kitchener is not far behind with 87% of kids in a child care desert, and Hamilton with 71% of kids in deserts. Click on the map below to see child care coverage by postal code. As you can already see below, if you don’t live downtown, there probably aren’t enough child care spaces.

Source: Child Care Deserts in Canada

On balance, a tax credit approach will likely be expensive and have little positive effect on child care affordability or availability for most. If anything, other provinces are moving in the opposite direction, towards a set-fee approach like in Quebec’s $8/day system, with B.C., Alberta and Newfoundland attempting to control fees directly. Without a boost in child care spaces, families will continue to wait.