The COVID-19 global outbreak has brought into sharp focus the threat of supply disruptions and shortages of critical medical products and equipment. In the U.S., as in many other places, efforts to contain the pandemic have exposed the limits of domestic stockpiles and industrial capacity, which has prompted concerns about import dependency.

For Canada, these concerns hit home in early April, with Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland likening the global scramble for personal protective equipment (PPE) to the “Wild West.” In the face of the U.S. export ban on shipments of N-95 respirators, the premier of Ontario essentially vowed to never again “rely on the kindness of strangers.”

While President Trump’s threats to restrict exports stoked fears, the respirators—produced by manufacturer 3M—were ultimately secured. Both federal and provincial governments have since taken measures to boost and diversify domestic production of key medical supplies, such as medical gowns, surgical masks, and hand sanitizer. But there appears to be little publicly available analysis that provides a sense of Canada’s import structure regarding COVID-19 related medical supplies and equipment.

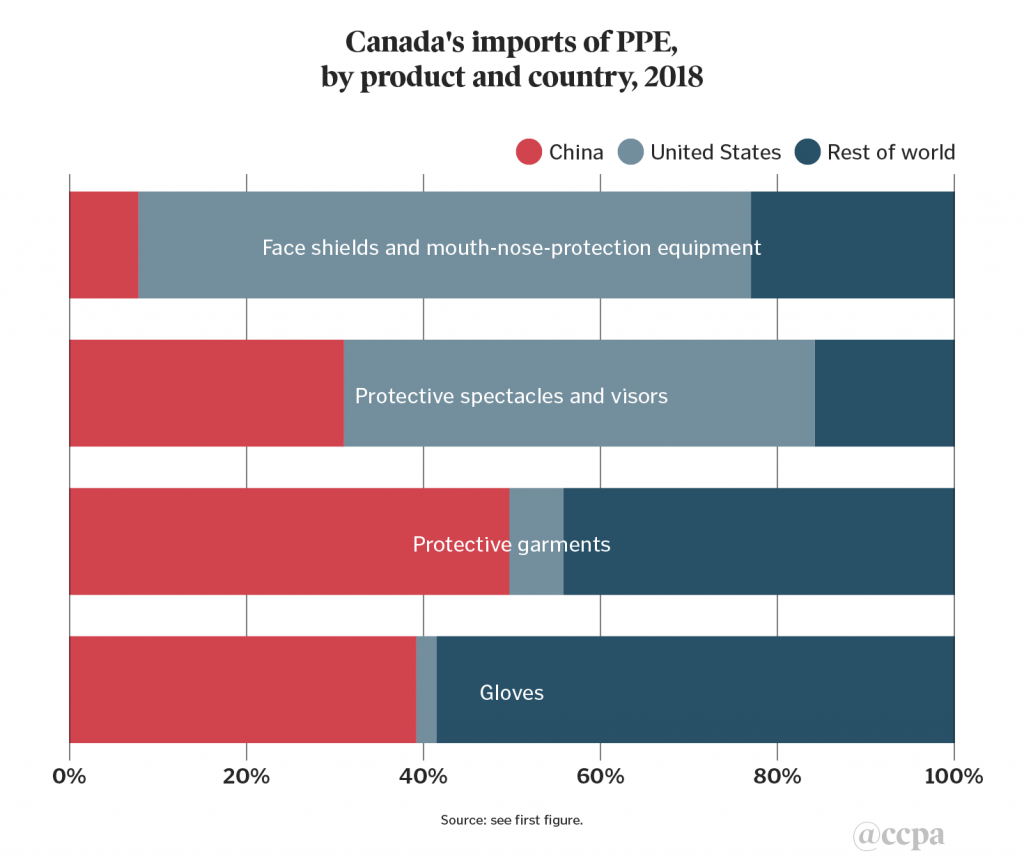

This short note is a preliminary effort to fill this data gap by adapting a methodology used in a recent Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) report to estimate U.S. dependence on PPE imports from China. The report examined U.S. imports by country for five main PPE product groupings: face shields, mouth and nose protection equipment, protective garments, gloves, and goggles and visors.

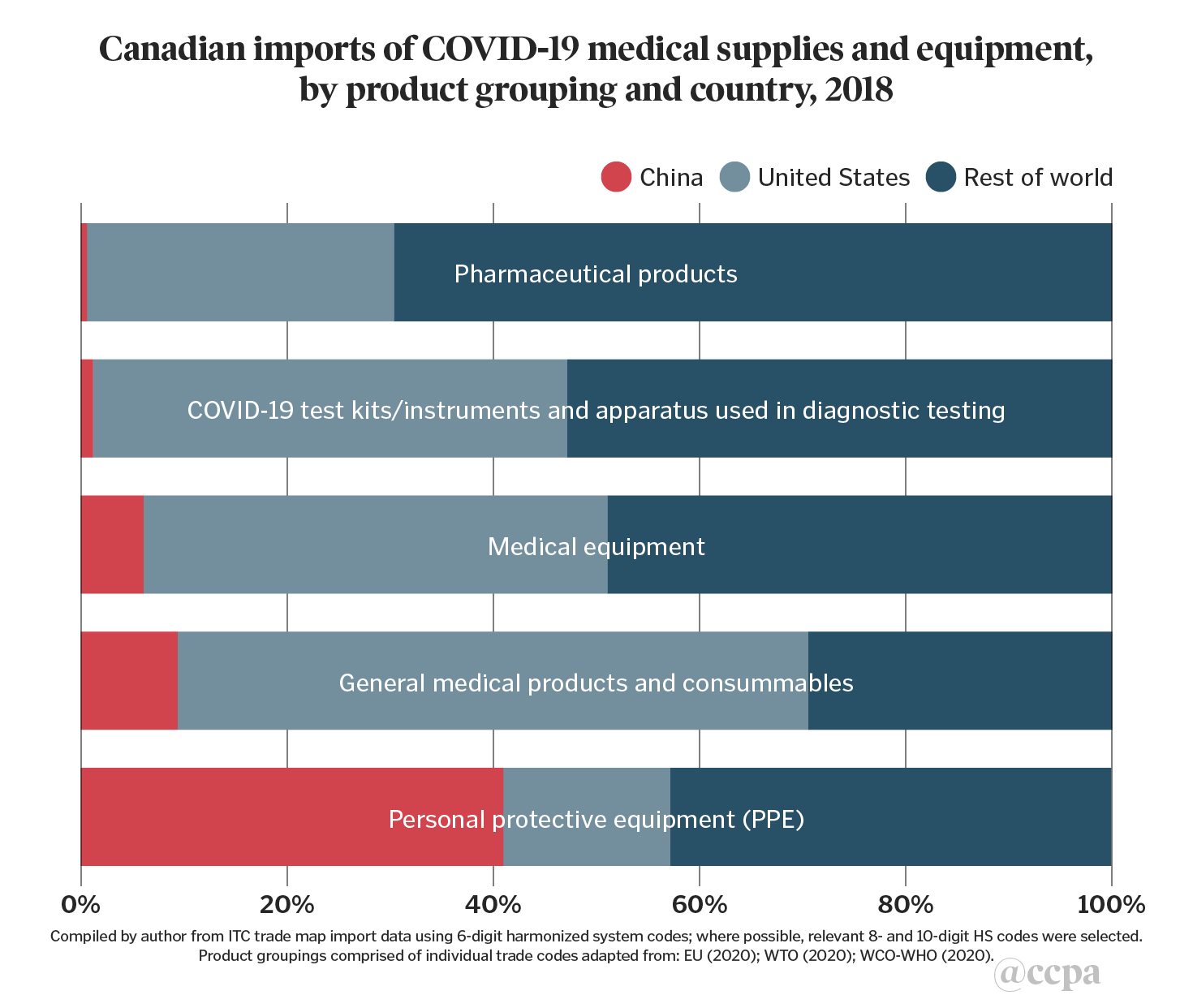

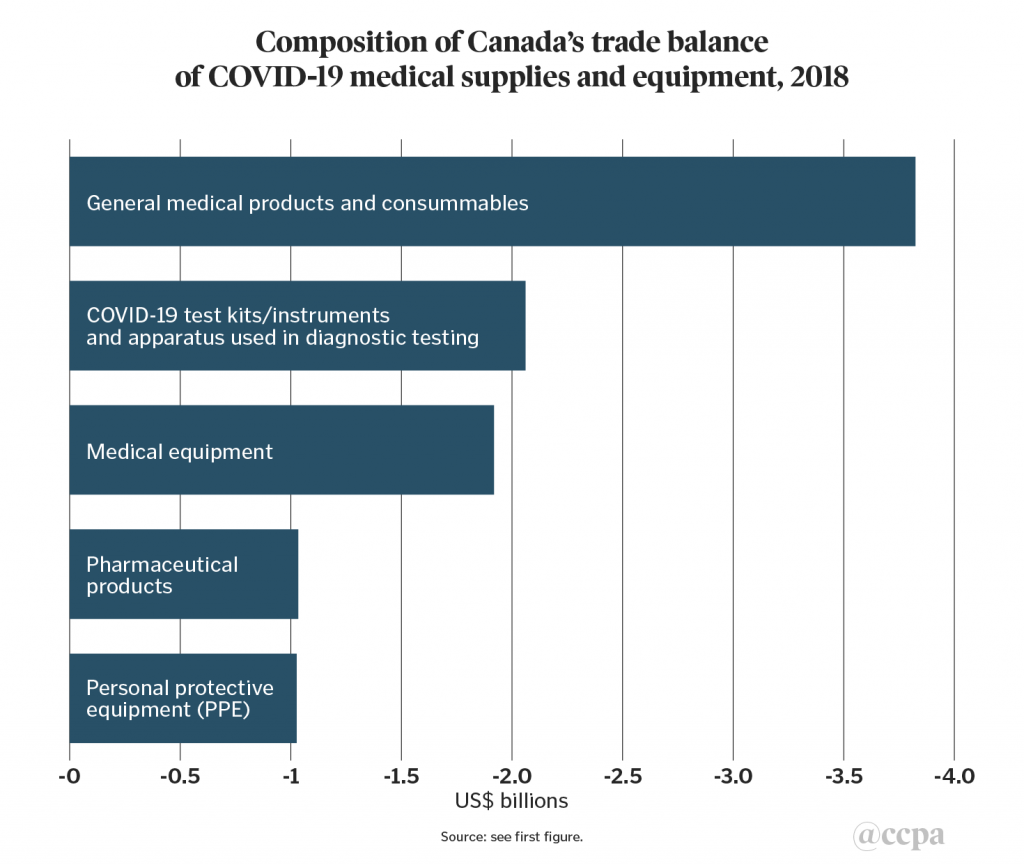

For the Canadian context, the first two charts presented below extend the methodology by adding a wider set of product groupings to include test kits and related instruments, general medical consumables, medical equipment, and pharmaceutical products, before providing a separate breakdown of imports of PPE product sub-categories. The third chart examines the composition of Canada’s trade deficit of COVID-19 related medical supplies and equipment, which totalled US$9.9bn in 2018.

The U.S. is a major source of imports of four out of the five product groupings in chart 1 with import shares that range from 30 per cent for pharmaceutical products, to 61 per cent in general medical products/consumables (which includes disinfectants, sterilization products, other reagents, and laboratory products).

These findings should come as no surprise given the degree of integration of the Canadian economy with U.S.-led global and regional value chains. Canada’s medical device sector is dominated by small- and medium-enterprises by number, but by foreign-owned multinational companies by market share.

In 2018, U.S. headquartered firms accounted for 17 of the world’s top 30 manufacturers in this sector by revenue.

Other advanced industrial economies are also major sources of Canada’s imports, such as Japan for COVID-19 test kits/instruments, Switzerland for pharmaceutical products, and Germany and the Netherlands for medical equipment. Imports from Mexico also feature prominently in certain items of medical equipment (for example: scientific measuring instruments, operating tables) and general medical products/consumables (ethyl alcohol, syringes, surgical sutures), reflecting the country’s participation in North American regional value-chains.China’s import share is less than 10 per cent in four of the product groupings.

Although it has made some export inroads across these groupings, its presence is more prominent in the supply of PPE, accounting for 41 per cent of Canada’s imports of these items in 2018. By comparison, the PIIE report calculated that China accounted for 48 per cent of U.S. PPE imports.

These estimates are consistent with broader trends of China’s gradual transition from exports of low value-added products to that of medium and high value-added market segments, across many important industrial sectors. In the area of medical supplies, this transition is evident in China’s strong role in Canada’s imports of PPE and, to a lesser extent, in general medical products and consumables (adhesive dressings, bandages, first-aid kits). It also shows up in sales of higher value-added items in certain medical equipment (thermometers, ultrasonic scanning machines, optical microscopes), and pharmaceutical products (antibiotic medicaments, immunological products).[1]

Canada’s imports of PPE can be further divided into product sub-categories, as shown in chart 2. At first glance, the 69 per cent U.S. share of Canada’s imports of face shields and mouth and nose protection equipment is striking, and highlights the sensitivity underlying the 3M respirator deal for Canada. China plays an important part in this supply chain, however, given an estimated 70 per cent U.S. import dependence on China for this item.[2]

Indeed, the 3M deal entails importing 166.5 million respirators to the U.S. over three months, mainly from its production facilities in China. This is about 1.6 times the company’s current monthly domestic U.S. production capacity (by unit volume).

China’s share of Canadian imports is significantly higher in the three remaining PPE sub-categories: 31 per cent for protective spectacles and visors, 39 per cent for gloves, and 50 per cent for protective garments. Indicative of the spread of global value chains, the latter two sub-categories are also notable in that the rest of world grouping mainly consists of suppliers from other developing countries and emerging markets such as Viet Nam, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka.

For the protective spectacles and visors sub-category, the other main supplier was Taiwan.As mentioned above, Canada’s trade balance in the five product groupings in chart 1 amounted to a US$9.9bn deficit. The largest trade deficit product grouping was general medical products and consumables (US$3.8bn), followed by COVID-19 test kits and instruments (US$2.1bn), medical equipment (US$1.9bn), pharmaceutical products (US$1.0bn), and PPE (US$1.0bn) (see chart 3).

Today’s concerns over COVID-19 related global supply disruptions and shortages illustrate broader trends in hyperglobalization that have accelerated over the past three decades. Market pressures pushed companies to seek short-term efficiency gains by reducing labour and logistical costs using global value chains and just-in-time management systems. At the same time, corporate mergers further concentrated the industrial base, ultimately making supply chains more cost-efficient when times are good, but leaving minimal domestic surplus capacity in times of a sudden urgent need.

The onset of COVID-19 has naturally spurred further re-thinking on the strategic role of the state in public health already underway in the wake of other major recent global events, such as the global financial crisis and the U.S.-China trade war. This has given impetus to more activist public policy approaches in finance, manufacturing, technology, and innovation. In addition to expanded reporting requirements for shortages in medical supplies and drugs, for example, the U.S. pandemic response legislation also included the conduct of security assessments of related supply chains.

Echoing shifts in economic policy seen in other major advanced economies, recent calls for a modern Canadian industrial policy are long overdue but will need to creatively overcome more than three decades of decision making steeped in laissez-faire Washington Consensus precepts. This preliminary analysis of Canada’s import structure is a contribution towards getting a grip on Canada’s essential medical supply situation in order to be better prepared for future pandemics or other supply chain disruptions.

Daniel Poon is an independent economist. He has previously worked with the UN Conference on Trade and Development, the International Labour Organization, and the North-South Institute. The author thanks Scott Sinclair and an anonymous reviewer for suggestions on an earlier draft.

[1] Estimates of Canada’s imports of pharmaceutical products by country in chart 1 consist of trade codes related to manufactured drug medicaments but not their underlying raw materials, known as active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). As such, the estimate of China’s share of Canada’s pharmaceutical imports is likely significantly undervalued since roughly 80 per cent of APIs used for US commercial manufacture of finished drug products are sourced from China and India. India’s generic drug industry is reported to depend on China for 70 per cent of its API imports.

However, according to recent US congressional testimony, the US Food and Drug Administration is not able to determine with any accuracy the “the volume of APIs manufactured in China that is entering the US market, either directly or indirectly by incorporation into finished dosages manufactured in China or other parts of the world.”

[2] This figure is probably an overestimate since the relevant 6-digit HS code for respirators (6307.90) used in the PIIE report likely includes several other items that are not related to respirators.