Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Well-being economies are designed to serve people and the planet. They do so by creating and empowering institutions, such as governments, to deliver an equitable distribution of wealth while protecting the planet’s resources for future generations.

The idea that the economy should exist to serve people and the planet seems sensible and appealing. But because of the carefully orchestrated narrative of the economy having a life of its own, whose needs we need to accommodate, some may perceive the idea of a well-being economy to be naïve and unfeasible, and thus hesitate to embrace its application.

In fact, the well-being economy is not just a nice idea. Its principles are being adopted in various ways and at various stages, in countries such as Iceland, New Zealand, Finland, Scotland, and even in Canada. The process is arguably most advanced in Wales.

In 2015, Welsh parliament passed the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act, following a “national conversation” around “The Wales We Want” for our children and grandchildren.

Wales is a country of approximately three million people with a parliamentary system of government. As a “sub-national” jurisdiction (governed by its own Welsh government as well as by the Government of the United Kingdom), its experiences may be relevant to Canadian provinces and territories. When the national conversation was initiated, the country had suffered from the decline of mining and heavy industry, and it was apparent that prevailing neoliberal economic ideas weren’t working for them.

The Wellbeing of Future Generations Act set out seven goals. The goals are about prosperity, which, notably, makes no mention of Gross Domestic Product or GDP and emphasizes the need for all people to be able to take advantage of wealth generated through decent work; resilience, which is understood in terms of healthy functioning ecosystems; health, including physical and mental well-being with a preventive orientation; equality, where people can fulfill their potential regardless of socioeconomic background or circumstances; community cohesion, meaning communities that are viable, safe, and well-connected; cultural vibrance, which includes robust arts, sports, and recreation sectors; and global responsibility, where global implications of local initiatives are considered.

There are 50 national indicators to assess progress, which range from healthy life expectancy at birth, including the gap between the least and most deprived (#2), to concentration of carbon and organic matter in soil (#13), to percentage of dwellings with adequate energy performance (#33).

Significantly, the Act recognizes that tackling inter-connected challenges of climate change, poverty, health inequality, etc. requires all of society working together from foundations of long-term thinking, prevention, and integration (coherence).

Nearly 50 public bodies are engaged, including Welsh and local government, local health boards, and local councils, along with public health, health services, national park, higher education, arts and culture, natural resources, and sports authorities.

The Act mandates the formation of local boards to assess local needs and decisions through a future generations lens. While private industry is not bound by the Act, there are indications that companies are seeing the value of its principles.

A critical component is the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, whose role is to provide advice and support to government and public bodies in taking a longer-term and coherent view on decisions. The commissioner’s job, in short, is to be the guardian of future generations. This individual is independent of government.

The commissioner is empowered to assess progress in relation to goals and to call out areas where progress is insufficient or inconsistent. Government ministers and other public bodies are obligated to respond to concerns brought forward by the commissioner.

The current commissioner, Derek Walker, noted in his remarks at the Well-Being Economy for Alberta conference that the position conferred considerable “soft power” in terms of providing an opportunity to raise concerns and to facilitate conversations between relevant players.

Walker provided a few examples of the impact of the Welsh initiative. One concerns plans for a major motorway, which was “practically a done deal,” even though it would have destroyed delicate wetlands and placed an immense burden on national finances.

After review by the commissioner, who challenged its impact in multiple domains, the project was cancelled. In addition to its immediate significance, this example sets an important precedent.

As another example, which Walker believes would not have happened in the absence of the Act and commissioner, the country is piloting a new funding mechanism—essentially a basic income—to support young adults who have aged out of the care system. The scheme provides approximately $2,600 in Canadian dollars ($2,100 after tax) per month to those leaving care at age 18, for two years.

In line with a well-being orientation, the stated rationale is that “Care leavers have a right to be supported as they develop into independent young adults. Yet, too many young people leaving care continue to face significant barriers… Basic income is a direct investment in this cohort of young people, giving them the space to thrive whilst securing their basic needs.”

Moreover, as described by former Commissioner Sophie Howe in a September 2023 address at the University of Vermont, the Act has underpinned a whole new transportation strategy, where walking and cycling are at the top, followed by public transit, followed by electric vehicles—with private motor vehicles at the bottom.

The strategy has permitted broad-scale reductions of speed limits, as well as a major shift of funding, from roads getting two-thirds of transport funding, to two-thirds now going to other means of transport.

The placement of electric vehicles (EVs) near the bottom of the strategy signals that while EVs may reduce emissions, they do not address global equity issues around extraction, nor do they resolve congestion and safety, thus aligning with the global responsibility goal.

We could learn many things from the Welsh experience, including the importance of clear foundational principles (coherence, long term orientation, equity), strong and cross-cutting legislation, broad buy-in, and the significant role of the commissioner.

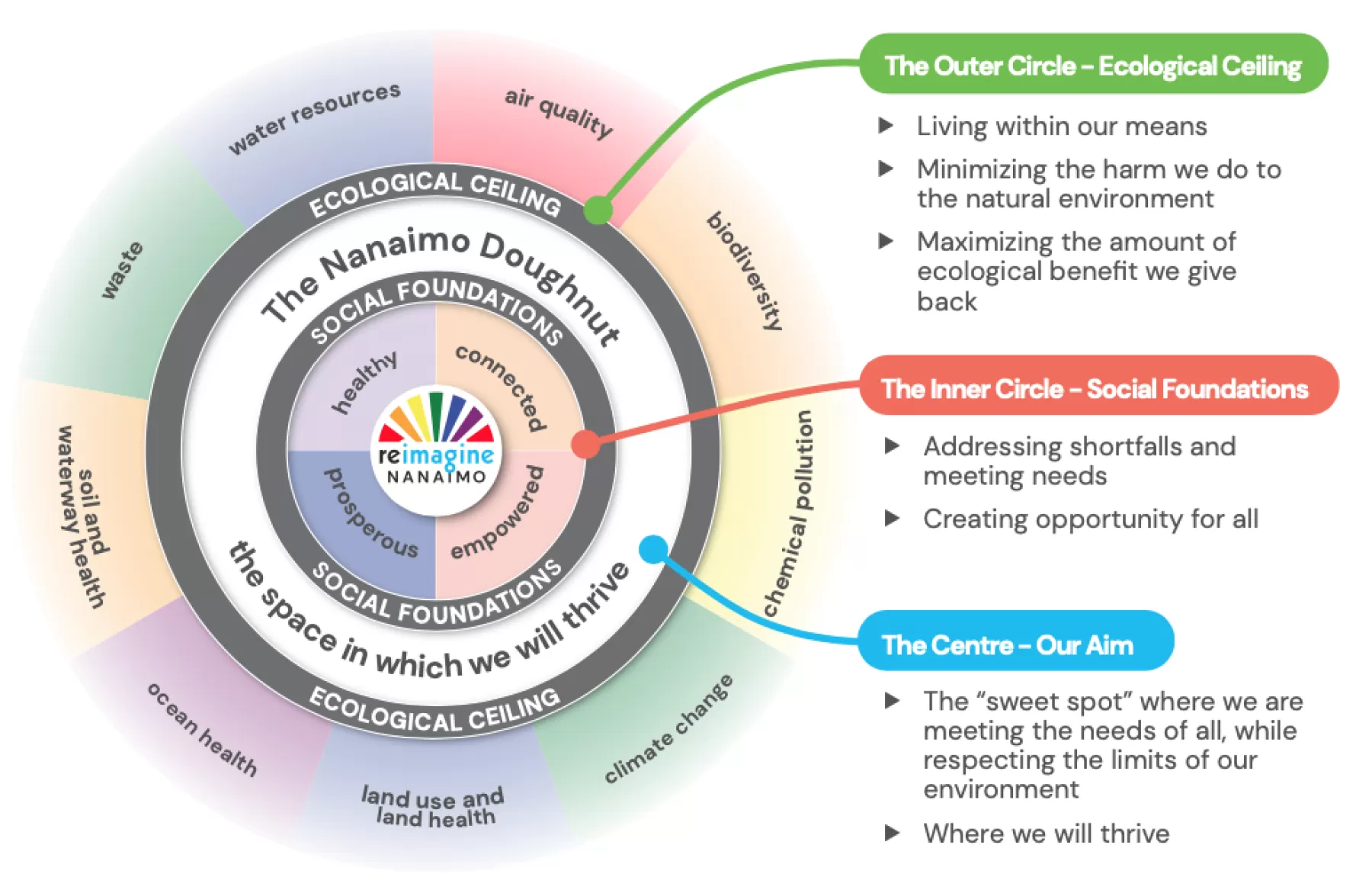

Nanaimo, B.C., a city of around 100,000 people on Vancouver Island, is using a very different set of legislative and policy tools to address similar challenges. Demonstrating the applicability of well-being economy principles here in Canada, the city has adopted doughnut economics, which aims to ensure that everyone has the social foundations needed to be well while not exceeding the earth’s life-supporting limits.

In his remarks at our conference, Nanaimo City Councillor Ben Geselbracht explained that city council developed a community plan guided by doughnut economy principles but tailored to the Nanaimo context.

}},249907:{type:captionedImage,enabled:true,collapsed:false,fields:{image:[249855],imagePosition:null,caption:Source: City Plan: Nanaimo Re-arranged.}},249908:{type:copy,enabled:true,collapsed:false,fields:{copy:

The plan, which is anchored in principles of integration (coherence) and adaptability (resilience), has five interconnected goals emphasizing, among other things, greenhouse gas emission reduction, healthy watersheds, urban tree canopies, affordable housing, walkability, and active and public transportation.

All city council decisions are made through a well-being lens and city staff have been directed to integrate the Nanaimo Doughnut into decision-making and the development of an outcome-based budget.

Nanaimo’s doughnut economy vision has supported important initiatives. One example is a municipal sustainable procurement policy, where procurement decisions must factor in greenhouse gas production, local vs. more remote origin, good labour practices, waste production, etc.

In other words, procurement activities are leveraged to advance environmental, social, and ethical objectives from the city’s plan.

Geselbracht highlighted challenges and tensions inherent in such a broad vision. For example, placing environmental limits on development is essential but can exacerbate housing shortages. This example points to the need to enhance advocacy to other levels of government that share responsibility for these important and interrelated goals.

Recent events further illustrate challenges. In the context of a B.C. provincial update to its building code to limit greenhouse gas emissions from new construction, Nanaimo recently announced that, starting July 1, 2024, newly built homes in the city will not be permitted to have natural gas as a primary heat source.

Almost immediately, this prompted a “cross-border political campaign” by the Canadian Energy Centre (neighbouring Alberta’s oil and gas “War Room”), including over 2,300 letters to Nanaimo’s city council urging them to reverse the move (which has, so far, not happened).

The Welsh government has likewise faced resistance to initiatives to reduce speed limits and limit road expansion—despite the potential of these policies to save lives, lower carbon emissions, and generally improve well-being, those opposed (including the UK prime minister) have labelled them “anti-motorist.”

While these challenges can feel disheartening, this is perhaps a good opportunity for us to remember that opposition to a well-being economy is to be anticipated, coming from those who benefit from the status quo. Moreover, resistance signals that we are working on something important. Let’s continue the good work together.