Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

The elections campaign is currently in full swing in Quebec, and three out of the four political parties represented in the National Assembly agree on the economic interest which lies in producing shale oil in Anticosti. Between the environmental risks of producing fossil fuels on this island in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the $14 billion economic benefits for both the Quebec government and its society, the choice seems inevitable: dig deep, but dig well (pun intended), i.e. by meeting the “highest environmental standards.” Even Daniel Breton, former Environment minister and ex-environmental activist, has rallied behind the cause and accepted the idea that we should at least explore the potential of these deposits, held by the new public-private partnership “Quebec, Petrolia, Maurel, and Prom.”

However, the near unanimous support ignores the more recent economic analyses of shale oil production in North Dakota’s Bakken Formation, which compares to the Macasty Formation on Anticosti Island. They lead us to conclude that the $14G Quebec City is dreaming about on Anticosti is to oil what mineral pyrite was to gold: a sham fooling inexperienced diggers, a fool’s gold leading them to their ruin.

Less than 5 years ago, the US were dreaming of achieving long-lasting energy independence by diving head first into shale oil production. They’re now quite disillusioned. The signs have become increasingly clear in the last year: shale oil no longer attracts high-profile private investments. It should come as no surprise since current results in no way justify the initial investments. A study led by consulting firm IHS Herald shows that in 2013 the oil industry’s biggest businesses worldwide had reduced their investments on US soil by more than half compared to 2012 and that they represent less than a tenth of investments made in 2011. The deposits’ potential has been overestimated.

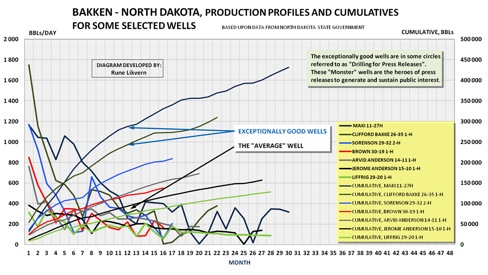

Hence, in 2013 Shell came to the conclusion that its fossil fuel properties were overvalued by $2 billion. The year before that, mining giant BHP Biliton has slashed by $2.8 billion the estimated value of its oil and gas assets. None of this is surprising: the data provided by the North Dakota government shows that —outside of a few wells with exceptional output, which have everybody talking— the majority of wells have a rather low weekly production and their useful life is getting shorter and shorter with passing years.

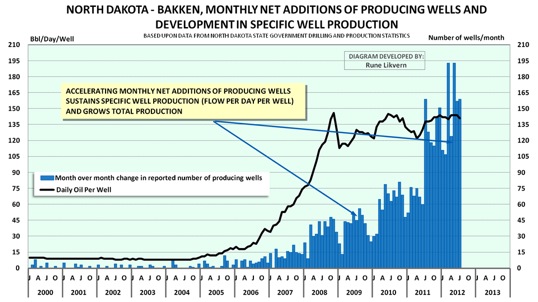

According to a number of analysts, production in Dakota is stuck in the Red Queen syndrome. In Lewis Carroll’s famous tale, the Red Queen tells Alice: “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” In the case of shale oil, this syndrome translates into a sudden and unexpected collapse of well productivity. The drop in turn forces the industry to dig more in the hopes of merely maintaining an output which can make previous investments in already existing infrastructure profitable. Thus, the shale oil industry is unable to develop in the long run even though it turned Dakota into swiss cheese.

The following graph, taken from a piece by Rune Likvern, energy and financial analyst, shows how well construction in North Dakota accelerated between 2000 and 2012.

In an ever harsher environment in which major companies are hesitating between jumping ship or cutting back on investments, all that is left are juniors trying hard to turn a profit. However these businesses are built on shakier financial grounds than majors and are more vulnerable to the vagaries of the financial market. They therefore seek out partners to solidify their position. That’s exactly what Petrolia just did with the Quebec government.

Previsions concerning Anticosti’s potential are based on the same overly optimistic calculations as we saw in Dakota. Does this in any way explain why Petrolia was unable to find any other international-level partners than Maurel & Prom, a declining company dragged down by numerous financial scandals.

It’s also likely that the Quebec government decided to invest massively in the Anticosti adventure in order to overcome this harsh context.

All in all, the important environmental sacrifices required to carry out oil production could be made only to find ourselves with “fool’s gold” in our hands, leading to no economic benefit whatsoever.

This article was written by Éric Pineault, an associated researcher with IRIS, and Bertrand Schepper, a researcher with IRIS—a Montreal-based progressive think tank.