Key facts:

-

Oilsands and meat packing workers have seen terrifying COVID-19 outbreaks as they’ve stayed open in the first phase of the pandemic.

- Child care workers, construction labourers, servers, cashiers, and bus drivers have almost identical high risk scores as industrial butchers but, so far, they have been protected due to layoffs.

- The risk of COVID-19 infection for oil sands workers is high but hairstylists, barbers, elementary school assistants, dental hygienists, and flight attendants have even higher risk scores. Their workplaces have been closed; re-opening puts them at risk.

-

Since February, 1.7 million workers who were at high risk of contracting COVID-19 due to their physical proximity with others at work were protected due to layoffs or reduced work hours.

- Of those 1.7 million workers, 69% (1.2 million) were women.

- There are 650,000 workers making $16 an hour or less who are at high risk but have been protected while at home likely relying on the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB).

-

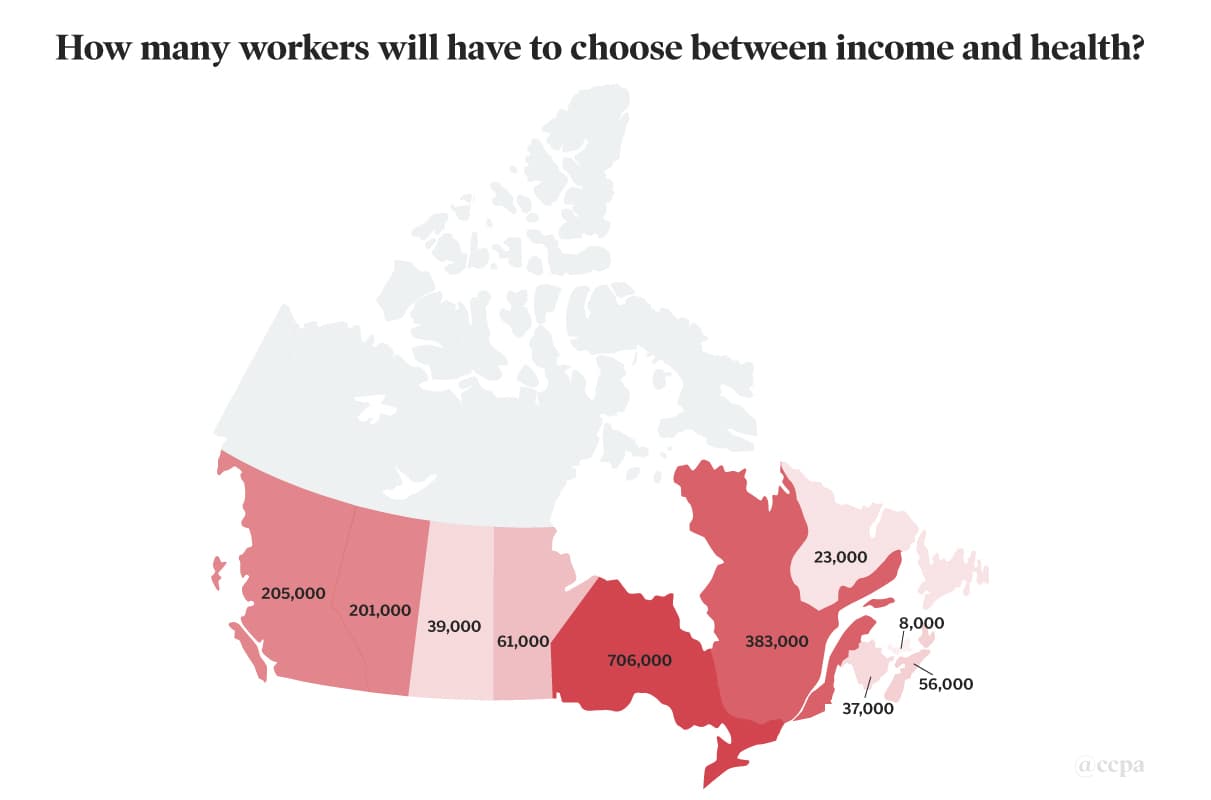

Nova Scotia protected, proportionally, the most high risk workers due to its shutdown; Saskatchewan protected the fewest.

- 383,000 high-risk workers in Quebec and 706,000 in Ontario have been protected while at home.

- The provinces need to have labour authorities rapidly act on complaints about inadequate COVID-19 protections in the workplace. The federal government should allow recipients to remain on CERB even if they refuse to return to a workplace that is inadequately protected against COVID-19.

With the COVID-19 curve flattening in many parts of Canada, provinces are rushing to re-open.

Quebec has already re-opened elementary schools outside of Montreal. B.C., Manitoba, and Alberta have or soon will re-open salons and barbershops. Following the long weekend, many Ontario businesses will be able to open back up.

With services re-opening, workers will be called back. For many of the recalled workers, their layoff or lost hours will have protected them from COVID-19 exposure at work. If they are at home, they have greater control over limiting their potential exposure to the virus, particularly if they work in occupations that put them in contact with many customers or other workers in their workplace. While far from perfect, the CERB does provide much better coverage than the old EI system ever did, allowing workers to stay home and have some income to support them.

The goal of the non-essential workplace shutdowns wasn’t to protect workers per se, it was to avoid overwhelming emergency rooms. However, workers in high-risk occupations effectively benefited. That benefit may soon be ending as workplaces open back up and workers must decide whether workplaces are safe and whether they can afford to refuse work that puts them at risk.

Which occupations can’t socially distance?

This analysis examines the physical proximity that workers have to others in their occupation. It uses the O*Net index of physical proximity translated into Canadian data, which provides a score (out of 100) for how close workers get to other customers or other workers. The complete list of occupations and their physical proximity is available here. The list of selected occupations below are just some of those in the high risk of infection category examined in more detail in this analysis.

Some of the occupations with very high scores in the selected list have remained open during the shutdown with few protections, particularly at first. In the case of oil and gas well drilling workers or industrial butchers, this close proximity at work led to dangerous outbreaks among workers at oilsands workcamps and both workers and inspectors at the Cargill meat packing plant in southern Alberta.

Other close proximity occupations are health related and were better prepared for COVID-19. These professions have worked throughout the pandemic to keep sick Canadians well. They include respiratory therapists, nurses of different designations, and physicians. Despite having good procedures and relatively good access to personal protective equipment, workers in these professions still fell victim to the novel coronavirus.

Selected Occupations by physical proximity score (2016) [table id=14 /] Source: O*Net, Brookings institute, 2016 Census and author’s calculations

Many of these high-risk occupations were completely shut down or were operating with much smaller staff during the first phase of COVID-19. As a result, they were protected from high physical exposure to COVID-19, since they were at home and could better isolate themselves.

However, many of these occupations have similarly high proximity scores as oil sands workers or meatpacking butchers. For instance, child care workers (76), construction labourers (76), servers (78), cashiers (75), and bus drivers (76.3) have almost identical scores to industrial butchers (77). For the most part, those other occupations have been almost entirely shut down, with workers protected while at home.

Oil and gas drillers are even more exposed, reflected in the COVID-19 outbreaks at oil sands labour camps. While their proximity score is high (87), the proximity score is even higher for hairstylists (92), barbers (92), elementary school assistants (88), dental hygienists (100), and flight attendants (96), but these workers have been protected by shut downs in their workplaces. It is unclear whether sufficient modifications could be made to their workplaces for them to be safe. We’re soon going to find out though as these businesses re-open in several provinces.

The score of physical proximity is used as a proxy for how concerned workers should be of being exposed to COVID-19 while at work if key safety measures aren’t put into place. Without measures like shields, personal protective equipment, and shift management, those working in high physical proximity workplaces are likely to be in hotspots for COVID-19 spread upon re-opening.

Who’s at highest risk upon recall?

This analysis sorts workers into four equally sized groups based on their occupation’s physical proximity score in February 2020. It includes the selected professions in the first table and all other workers with similar proximity scores. The highest physical proximity group is named high risk and will require key changes in the workplace to make it safe for them to return.

The countrywide shutdown saw plenty of workers being laid off or losing most of their hours, however, those workers weren’t all in high-risk occupations. Many workers in only medium-risk occupations also lost work or hours. It is really only workers in the lowest-risk occupations who were spared many of the job losses.

In total, there are 1.7 million workers in high-risk occupations who’ve lost their job or the majority of their hours since February. It is these workers, if called back, who may face the highest risk of infection if employers aren’t adequately protecting them. Although in some cases, like child care workers, it will be very difficult to adequately protect workers from COVID-19, even with the best policies.

Even though job and hour losses are roughly equal between genders, their risk upon return is anything but equal.

Between February and April, 27% of men and 30% of women lost jobs or the majority of hours. However, women are twice as likely to be returning to a job with a high risk of physical proximity.

Of the 1.7 million high-risk workers protected while at home during the shutdown, 1.2 million of them are women. This compares to 526,000 male workers who are in a high-risk occupation but are also presently at home.

This is largely due to the types of industries that were closed and their gender breakdowns. For instance, the first round of layoffs were in the food, retail, hotel and accommodations, arts and culture, and secondary health care industries. All of these industries are dominated by women and are also characterized by plenty of physical contact with others.

The second round of layoffs in trades, transport, heavy equipment and maintenance hit men harder, although these are generally occupations with less physical contact.

Workers in some provinces were better protected than others, given their industrial breakdown.

In Nova Scotia, 43% of high-risk workers have been protected due to layoffs and hour losses.

On the other hand, only 27% of high-risk workers in Saskatchewan were protected by staying home during the shutdown.

As provinces re-open, it is worth understanding how many workers will be put in harm’s way without significant changes to workplaces.

In raw numbers, Ontario saw 706,000 workers in high-risk occupations protected by its shutdown—the most of any province, although Ontario had the most workers, in general, in February.

The other large provinces—Quebec (383,000), British Columbia (205,000), and Alberta (201,000)—all had significant numbers of workers who were protected by the shutdown.

At this point, Ontario looks to be further away from re-opening, providing more time before recalled workers have to decide if they want to return to a high-risk workplace.

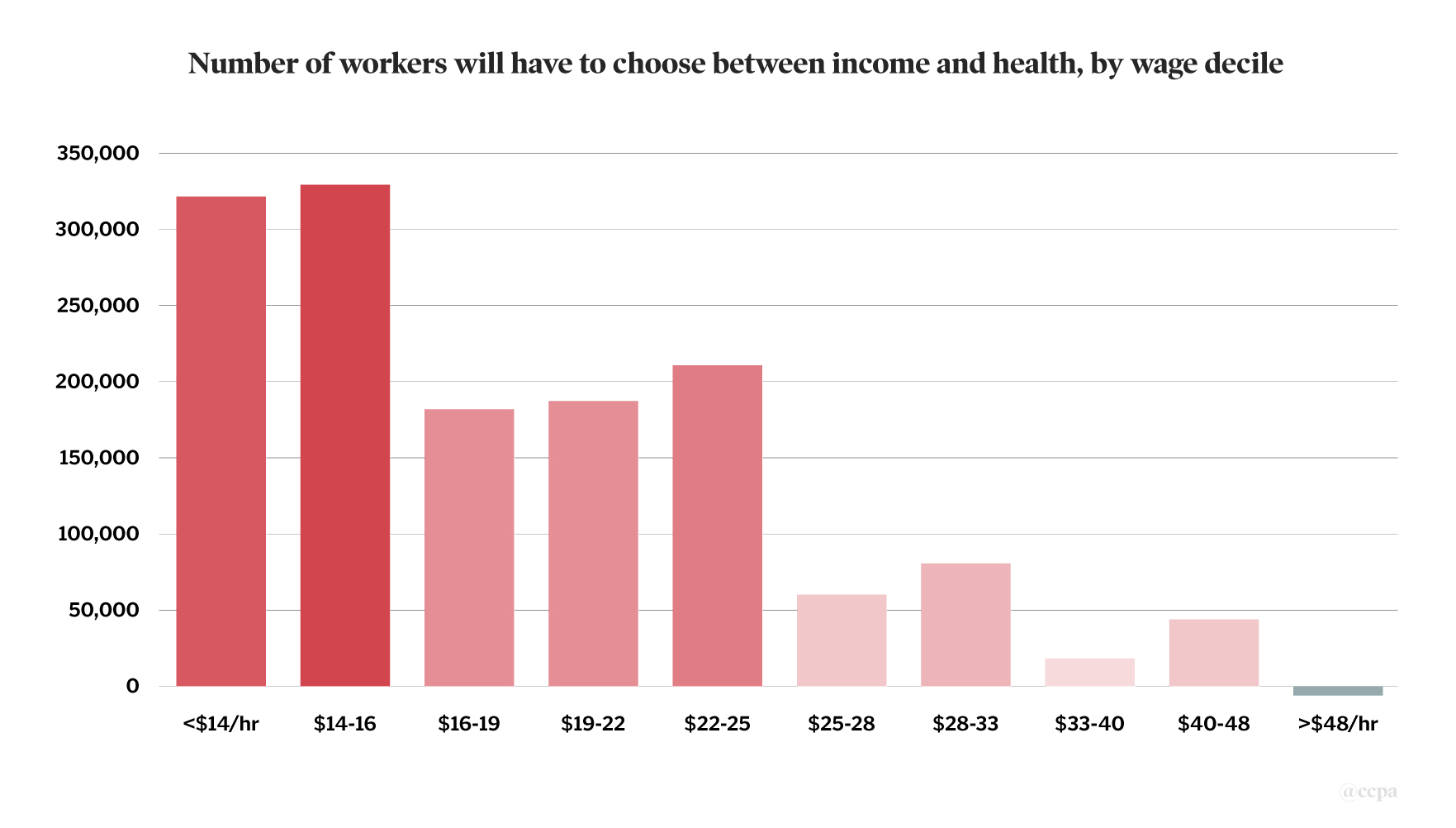

The burden of choosing between health and income will fall most heavily on low-wage workers. It is overwhelmingly low-wage workers who lost their jobs or the majority of their hours over the past two months.

Half of those making $16 an hour or less lost their job or the majority of their hours since February. Many of these workers also had high-risk occupations.

There are 650,000 workers making $16 an hour or less who are currently protected from the COVID-19 shutdown, but their occupations are high risk.

The richest 10% of workers making over $48 an hour have seen almost no one in a high-risk occupation protected due to layoff or loss of hours, but this is because almost no one has lost their jobs at this high a pay rate.

What this analysis makes clear is that millions of workers face a high risk of contracting COVID-19 once their workplaces re-open. Many of those workers are women and low-wage workers who will find it difficult to turn down work, even if it is risky.

CERB rules may make things worse

The safety of workers, particularly in high physical exposure occupations, will be critically dependent on how well prepared their employers are to protect them.

Barriers, adequate personal protective equipment, and other policies like shift scheduling can significantly reduce workers’ risk. However, these measures are hardly universal on employers’ part. For instance, employers at meatpacking plants in Canada and the U.S. have seen very serious outbreaks, suggesting that existing protective measures that have been taken were insufficient.

In some occupations, like teaching or child care, it may be close to impossible to substantially reduce a worker’s risk, despite an employer’s best intentions.

If workers are recalled to work but don’t go, they may well receive a record of employment saying that they quit. If a worker quits, they aren’t eligible for the CERB, except in the case of having to stay home to care for children.

If a worker doesn’t return because they don’t believe the workplace is safe due to inadequate COVID-19 protections, they’d have to file a complaint with the provincial health and safety authority and if the ruling was in their favour they could likely still receive CERB. However, this is largely a hypothetical, rather than a practical, avenue for workers.

In Ontario, for instance, there seems to be essentially no investigation of complaints related to COVID-19. Without rapid new provincial initiatives to investigate claims, workers could easily be forced to quit instead of working in a COVID-19 hotspot—losing their only income support, CERB, in the process.

Employers could easily abuse the situation by threatening workers that their CERB will be cut off if they don’t come back to work. Any discussion of incentivizing workers would need to take into account this sort of “stick” approach that employers could easily use to force their low-wage workers back to work instead of making a workplace safe.

While provincial inaction on unsafe workplaces in a pandemic is outside of federal jurisdiction, there is still a role for the federal government. It could add an additional quit exemption to CERB, allowing workers to quit due to COVID-19 related unsafe workplace conditions.

This would allow workers to quit jobs that they consider unsafe and still receive CERB.

It would also even the playing field, incentivizing recalcitrant employers to do the right thing and provide adequate protections in order to retain their workers.

Without this needed worker protection, talk of incentivizing workers becomes a nice way of talking about forcing low-wage workers back into unsafe workplaces because they’ll otherwise run out of money for things like food and rent.

That’s a dilemma that we should be working hard to avoid, and quickly.

Author’s note: Additional research has been conducted using the O*Net physical proximity and exposure to infection occupation data.

The New York Times utilized this approach in their March 15th analysis on the U.S.

The Jobs at Risk Index in the UK is also based on this approach.

In the Canadian context, the Brookfield Institute has visualized the risks to Canadian workers.

MaRS further analyzed Ontario essential workers and the risks they faced in their occupations.

More recently, the University of British Columbia has created a tool to assess risk for Canadian workers.