November can feel like a bleak month. The crisp bright beauty of October fades away and a colder, quieter grey sets in as we prepare for longer, darker nights. On the heels of a particularly uninspired election season, with protests at hospitals across the country and Canada battling a Delta-fuelled fourth wave, this fall seems a little darker than most.

Knowing that uncertain days were ahead, we wanted to offer a counterbalance to the partisan jabs, the daily COVID-19 counts, the doomscrolling. In preparation for this issue, I asked the contributing authors for their Big Ideas. More specifically, I encouraged them to think of progress as a relay race. No one person or single moment can be responsible for fixing everything. So if this was their moment and the baton was passed to them, what would be their big idea to advance equity and sustainability in Canada? And how can we divorce our thinking about progress from the limited imagination that four year election cycles afford us? I’m thrilled to share this collection of ideas for Canada’s future, and I hope that it makes your November a little brighter.

The big idea that I’ve been sitting with this fall is one that we can commit to at the individual level but that also scales well to the community, organization and government level. That idea is reconceptualizing how we think about, talk about and practice accountability. I was reminded of the need for a re-evaluation on twitter where some Black and Indigenous organizers that I follow were expressing their skepticism about taxing the rich. Up until that point, I had considered taxing the rich to be a slam dunk policy proposal with widespread support. But these organizers explained that increasing tax reserves within the current system would only lead to increased spending on things that threatened their lives and the lives of their loved ones: policing, military and incarceration. When we talk about taxing the rich, we do so in a framework that also imagines a budgeting process that prioritizes progressive projects like pharmacare and housing. We imagine a budgeting process that puts people first. Put another way, we imagine a budgeting process that is accountable to communities.

In her writing, Mia Mingus explains that people typically think of accountability as something external, i.e., we hold other people accountable. But accountability, she posits, is an intrinsic process; it can’t be put upon you. By the same token, accountability is not a tool of enforcement or punishment. Instead, accountability is a generative process that strengthens and repairs a relationship. In order to fulfil this potential, though, accountability must be offered proactively. We must show up when we make mistakes or cause harm and we must be present for the people that are harmed or affected by our actions.

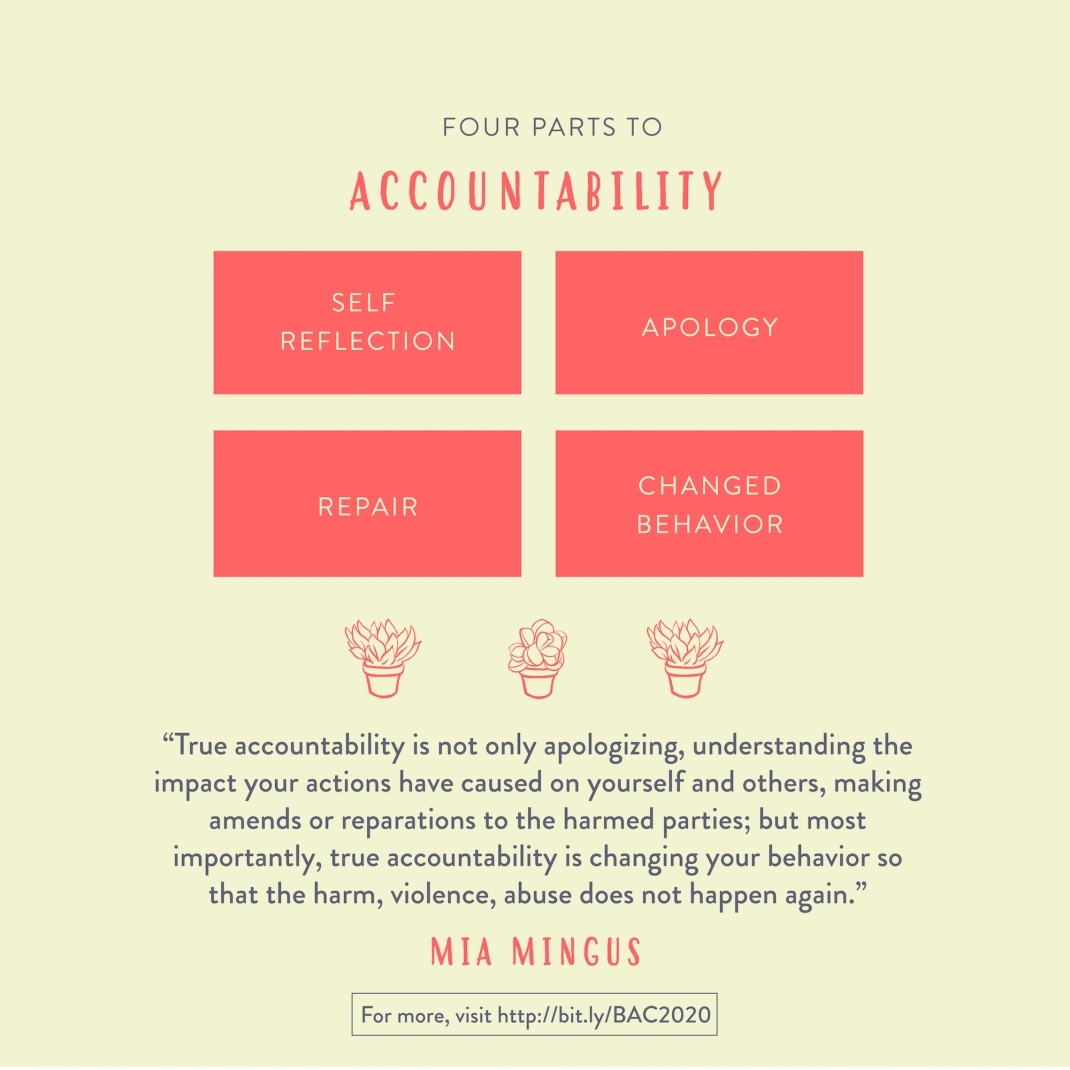

Mingus divides accountability into four key components: self-recognition; apologizing; repair; and behavioural change.

[Image designed by Danbee Kim that reads, “Four Parts to Accountability: self reflection, apology, repair, changed behavior.” Each part is in a separate red box, with a drawing of three small potted plants underneath. A quote by Mia Mingus at the bottom reads, “True accountability is not only apologizing, understanding the impacts your actions have caused on yourself and others, making amends or reparations to the harmed parties; but most importantly, true accountability is changing your behavior so that the harm, violence, abuse does not happen again.” There is a small box at the bottom that reads, “For more, visit http ://bit.ly/BAC2020”]

Why is accountability a big idea? The way that Mingus invites us to be accountable runs counter to the policing model of accountability we are typically taught: to understand accountability as something that is placed upon us when our misdeeds are revealed.

A generative and proactive accountability is a particularly transformative idea at this stage of the pandemic. As adrienne marie brown details in We Will Not Cancel Us, “Our emotions and need for control have been heightened during this pandemic—we are stuck in our houses or endangering ourselves to go out and work, terrified and angry at the loss of our plans and normalcy, terrified and angry at living under the oppressive rule of an administration that does not love us and that is racist and ignorant and violent. Grieving our unnecessary dead, many of whom are dying alone, unheld by us. We are full of justified rage. And we want to release that rage.” Finding space to practice and receive accountability when the world is upside down is truly a tall aspiration but a worthy one all the more.

As we square up against the myriad challenges of the climate crisis, we need everyone pulling together. But that’s not possible without people in power first becoming accountable to the communities most affected by these crises.

When scaling accountability up to the organization and government level, power dynamics and the exponential capacity to cause harm become key factors in creating and practicing accountability.

I had the privilege of speaking with a Semester in Dialogue class last fall at Simon Fraser University. We talked about the future of cities and the role of civic engagement in city planning. What the students had noticed was that survey and engagement event participants tended to be fairly homogenous, skewing white and middle-aged and coming from higher socioeconomic demographics. They asked the city staff person at the session why other communities didn’t feel compelled to participate in these activities.

I told the students about a report I had read earlier that year that had the goal of ensuring that low-income and racialized residents were “at the table” when decisions were made. The report didn’t say that these groups would be key decision makers, just that they would be in the room with decision makers when decisions were made. This kind of two-dimensional accountability checks a box but doesn’t ensure that residents who have entered into these relationships are being heard or that the people in power are being accountable to them. I offered the metaphor of a flickering candle. If your candle only has so much light left to give, you are less likely to share it with people in power who intend to tokenize your presence and not meaningfully engage you. It’s inevitable that people will stop showing up when there is no genuine accountability. As we face an uncertain future with what remains of this pandemic and its recovery, as we square up against the myriad challenges of the climate crisis, we need everyone pulling together. But that’s not possible without people in power first becoming accountable to the communities most affected by these crises, and the economic and systemic injustices that have contributed to their deepening impacts.

We can’t immediately fix the lack of accountability at a macro level in Canada. We can’t promise that a more equitable tax system would fund more equitable programs. But we can start the practice of embracing accountability on an individual level. Because the more familiar we become with the language and practice of accountability, the easier it will be to demand it from our institutions and our leaders. “We all have work to do. Our work is in the light… be accountable and go heal, simultaneously, continuously,” adrienne marie brown reminds us. “It’s never too late.”