Brad Wall has a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad idea for Saskatchewan; privatizing SaskTel. While the suggestion of privatizing Sasktel has been floated by the government for the past year, the idea took on new life yesterday with the Premier once again musing about the possibility of a referendum on privatization should the right offer materialize:

“If we were to get an offer as a result of the offer that’s happened in MTS for a majority of the company and we believed that it was good for the province for any number of reasons, it checked a lot of boxes in terms of keeping jobs in Saskatchewan, the head office here, better coverage, well then I can’t say yes to that deal because we didn’t campaign on that,” Wall said. “But I don’t think I should say no either without checking with the shareholders.”

The Premier obviously believes that there is a scenario in which a privatized Sasktel would be good for the people of Saskatchewan – as long as certain conditions are met. Could this be the case?

To evaluate the desirability of privatization, I think we need to look at a few different variables, such as affordability, access to service, quality of service and return on investment to determine whether we as a province would fare better under a privately-owned or publically-owned telecom.

Affordability

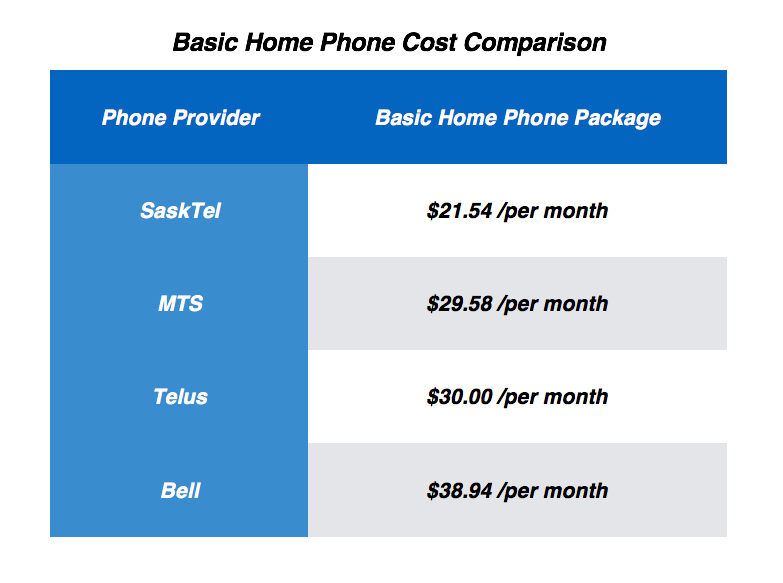

Let’s look at your bare bones landline package first. As you can see, for a basic home phone package, Sasktel is by far the most affordable. But obviously, landlines are increasingly becoming an anachronism, most people are going to be more interested in mobile phones and data packages. So here’s a Canadian Radio-Television Commission (CRTC) cross-country comparison of 1GB data plans. As you can see SaskTel slightly higher, but still pretty competitive – particularly in relation to the rest of the country.

So here’s a Canadian Radio-Television Commission (CRTC) cross-country comparison of 1GB data plans. As you can see SaskTel slightly higher, but still pretty competitive – particularly in relation to the rest of the country. However, a one GB plan is pretty small, how about the larger, more popular data plans? As you can see below, for 10 GB to unlimited data plans, SaskTel is the best in the country.

However, a one GB plan is pretty small, how about the larger, more popular data plans? As you can see below, for 10 GB to unlimited data plans, SaskTel is the best in the country. One thing to notice is how important regional carriers like a SaskTel or a MTS are to cost competitiveness. As you can see, in regions where there are only the three national carriers, prices are much higher. Given the most likely privatization scenario would have SaskTel gobbled up by one of the big Three national carriers – like the proposed MTS sale to Bell – it’s this three carrier scenario that would be the reality for Saskatchewan if we privatized.

One thing to notice is how important regional carriers like a SaskTel or a MTS are to cost competitiveness. As you can see, in regions where there are only the three national carriers, prices are much higher. Given the most likely privatization scenario would have SaskTel gobbled up by one of the big Three national carriers – like the proposed MTS sale to Bell – it’s this three carrier scenario that would be the reality for Saskatchewan if we privatized.

But don’t take my word for it – here’s the judgement of the CRTC:

“In the territories of the Regional Carriers, the result of this competition is clear – prices are lower, customers receive more data and more vigorous competition than elsewhere in Canada. In the territories of the Regional Carriers, wireless plans are as much as $50 to $70 per month less than their equivalents in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia.” – Telecom Notice of Consultation CRTC 2014-76 – Review of Wholesale Mobile Wireless Services.

Also, in markets that are reduced from 4 to 3 wireless carriers, not only do prices tend to rise steeply but data caps become smaller and the cost of data on a per GB basis becomes far higher. In fact, for customers of the big three (Bell, Rogers and Telus) you can’t even get Unlimited data — all their wireless packages have data caps. Unlimited data is only available in Saskatchewan from SaskTel and in Manitoba from MTS (for the time being).

So there’s no question that in terms of affordability, SaskTel is extremely competitive – offering the lowest prices in the country for larger and unlimited data plans. However, in Saskatchewan we also need to be cognizant of access to service, because ultimately it doesn’t matter how cheap a service is if you cannot access it.

Access to service

Saskatchewan is one of the most sparsely populated provinces in the country with about 1.8 persons per square kilometre of land. This is obviously a concern for a telecom company that has to make expensive investments in infrastructure that will serve less dense, and therefore less profitable areas. So how does SaskTel stack up in regards to access?

SaskTel has built its LTE (4G) network to cover 56% of the population of Saskatchewan, while its 3G covers 98% of the population in the province. How about the private carriers? Well, once again, the CRTC notes that those that have made investments in infrastructure in the province have primarily stuck to the more dense and therefore more profitable areas.

Those that do build in Saskatchewan, extend their newer technologies only to Regina and Saskatoon:

“In contrast, in the respective regions of the Regional Carriers, the National Carriers have predominantly built in urban centres, not making the same extensive wireless investments in high-cost rural areas across each of their operating territories like that of the Regional Carriers. For instance, SaskTel has built its LTE (4G) network to cover 56% of the population of Saskatchewan, while UMTS/HSPA+ (3G) covers 98% of the population in a province with a population density of some 1.8 persons per square kilometre of land.

The National Carriers who choose to build in Saskatchewan extend newer technologies only in Regina and Saskatoon, with population densities of some 61.8 and 50 persons per square kilometre, respectively. – Telecom Notice of Consultation CRTC 2014-76 – Review of Wholesale Mobile Wireless Services.

This is an obvious concern for rural Saskatchewan who rightly fear they would be neglected in a fully privatized telecom environment.

Here’s David Marit, the president of SARM expressing this fear:

“We are very fortunate in this province to have a provider (in SaskTel) that looks at rural just like they do anything else. We do have the private telecoms in this province – the Teluses and the Bells of the world. But they are not in rural. They won’t go to rural because of the numbers and what it costs them to set up. They just won’t go there.”

We can see in the chart below of capital intensity that SaskTel appears to make greater investments in its capital infrastructure than the other major carriers:

Capital intensity is the percentage of a company’s total operating revenues that are reinvested into capital expenditures like infrastructure. What’s interesting is that from a private investor’s perspective, this high rate of re-investment is viewed as a liability – as it means less money is returning to shareholders as profits and dividends. But as a Crown Corporation that is committed to making crucial investments in the province – particularly in underserved rural areas, this should be viewed as a positive.

Now it may be that any privatization would be contingent on promises to invest and expand service in rural areas. But such a promise – if it could be enforced – would require either a drastic reduction in the sale price due to the lack of profitability in servicing these areas or massive government subsidies. Rural Saskatchewan’s access to high quality telecommunication services seems much more certain and secure under public ownership.

Service quality

So a good gauge of service quality is to take a look at the number of complaints lodged against a company. In Canada we have the Commissioner for Complaints for Telecommunications Services which catalogues all the complaints lodged against the various telecoms throughout the year. Given each provider is going to have differing numbers of customers who each may have differing numbers of services we look at the complaints per one million access connections – an access connection could be a wireless plan, home-phone, TV, etc. As you can see, SaskTel has the lowest number of complaints per million access connections of any of the major telecoms.

Moreover, Wind Mobile, which had a comparable amount of total access connections to SaskTel, registered almost 20 times the number of complaints compared to SaskTel. To quote the Mark Goldberg and Associates Risk assessment of SaskTel, SaskTel’s total of just 16 complaints is “remarkably low.”

Return on investment

The last variable I want to look at is “return on investment.” Now, what return on investment means for a Crown Corporation can be tricky – because it may not be pure profitability, it may be providing good jobs and ensuring a diverse and highly-skilled workforce, it may be ensuring the lowest-cost, highest quality service, it may be the amount of money invested in communication infrastructure in the province – or it may be trying to strike a balance between all of these goals. So depending on what we want our Crown to do, return on investment may not just be a matter of money.

But let’s say for the sake of argument it is just a matter of money, that we only care how much money can be returned to the public purse. What type of ownership is best positioned to accomplish that – public or private?

Below we see how much revenue MTS has returned in cash income tax versus what SaskTel has returned as dividends in millions of dollars. As you can see, MTS has done a spectacular job of avoiding income taxes – so much so that it has paid a grand total of $1.2 million in cash income tax in the past decade. During the same period, SaskTel returned over $800 million to the province of Saskatchewan. How is this possible?

How is this possible?

A few years ago, MTS purchased communications firm Allstream in a deal worth $1.7 billion. Aside from expanding MTS’s business, the company “gained the benefit” of all of Allstream’s tax loss carry-forwards, which are past losses that can be applied to reduce future taxes owing. Today, the company has a “tax asset” or “tax shield” worth $300 million that it can use against any tax balances owing.

MTS estimates it won’t pay any cash taxes until at least 2019, and has pushed back the date when it expects to start paying tax at least five times in the past decade. To think that any potential buyer of Sasktel wouldn’t employ the same tax avoidance strategies to the best of their abilities is tremendously naive.

Now one of the arguments made in favour of privatization is that SaskTel wont be able to return the same level of dividends in the future. That is one of the possible predictions of the Goldberg and Associates Risk Assessment.

Over the past decade, SaskTel has delivered an average yearly dividend of $80 million to the province, but you could cut that in half, or even cut it by two-thirds and you would still be collecting far more in revenue than what the privately-owned MTS has delivered to Manitoba over the past ten years. Once again, in terms of pure cash return on investment, Sasktel is far superior to the private sector.

Conclusion

On affordability, access to service, quality of service and return on investment, publicly-owned SaskTel is far and away the better performer. Now there is one last argument you could make for selling SaskTel, and that is the Premier’s argument that you could use the proceeds of a sale to eliminate the province’s operating debt, which the Premier estimates is over $4 billion.

Now this is incredibly shortsighted in my opinion, but even if we take the argument seriously, we will see it’s simply not worth the cost.First off, the value of SaskTel is nowhere near $4 billion, probably closer to $2.3 billion.

But if you impose conditions on the sale – such as forcing the private carrier to service and make investments in unprofitable rural areas or ensuring certain employment levels or requiring headquarters in Saskatchewan, you are limiting the potential profitability of the private carrier and therefore would have to negotiate a diminished sale price.

And as the Premier assures us, these types of conditions would be a part of any deal, so the actual sale price might be well below $2.3 billion.Coupled with that, any sale price would more than likely also have to pay off SaskTel’s current debt – which sits at $870 million – also significantly reducing the sale price. Add to that the price of covering pension obligations, as well as costly consultants and legal fees to coordinate the sale (which were over $10 million alone for the MTS privatization way back in 1996) and the province might conceivably make closer to one billion dollars from any potential sale.

As the above should amply demonstrate, there is simply no good argument for selling SaskTel. The cost to the province of losing the most affordable rates, rural access to service, investment in critical infrastructure and annual dividends in the millions in exchange for sale proceeds that might only eliminate a quarter of the province’s operating debt would have to be characterized as the most reckless, short-term decision in Saskatchewan’s history.

And as we all know, we have a pretty rich history of reckless, short-term decisions.

Simon Enoch is the Director of the Saskatchewan Office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. He holds a PhD in Communication and Culture from Toronto Metropolitan University.