It’s that exciting time of year when economists wake from their summer slumber and start making submissions to the federal Finance Committee about what they’d like to see in Budget 2018.

So what would a feminist budget look like? Here are few things I’d like to see under the budget tree this year.

1) Invest in the sectors where women work

Men and women tend to work in different jobs in Canada. Moving women into predominantly male employment sectors may pay off for women in the longer term, but the rate of change is slow. Like, generational. Worse yet, research has shown that as the share of women in a field increases, the value placed on that work diminishes.

That means Budget 2018 needs to invest in the sectors where women are working today. More than one out of every five women in the labour force works in health and social services. Not construction (12% women). Women work in jobs that accommodate their unpaid work (particularly childcare), thus nursing, teaching and service industry jobs continue to be among those where women are most likely to be employed. We need job stimulus for the entire labour force, not just 53% of it.

2) Invest in a living wage

The occupations in which women are most likely to work include some of the lowest-paying jobs in Canada.

For example, women in skilled trades are most likely to work in food service and cosmetology, while men are most likely to be plumbers and electricians. Apprenticeships for all these trades require equivalent levels education, experience and skill, yet the average full-time wage for a cook is just under $29,000 and for a hairstylist it is $22,000. Contrast this to the average full-time wage for a plumber, which is $55,000, or for an electrician, which is $60,000 annually.

The government has promised to spend $3 billion in home care in the next three years. While this will certainly create jobs in a predominantly female job sector, the median take-home pay for a home care worker ($18,942) falls below the Low-Income Measure. Instituting a living wage for home care workers would make a good start to ensuring that working women aren’t living in poverty.

3) Supports for part-time workers

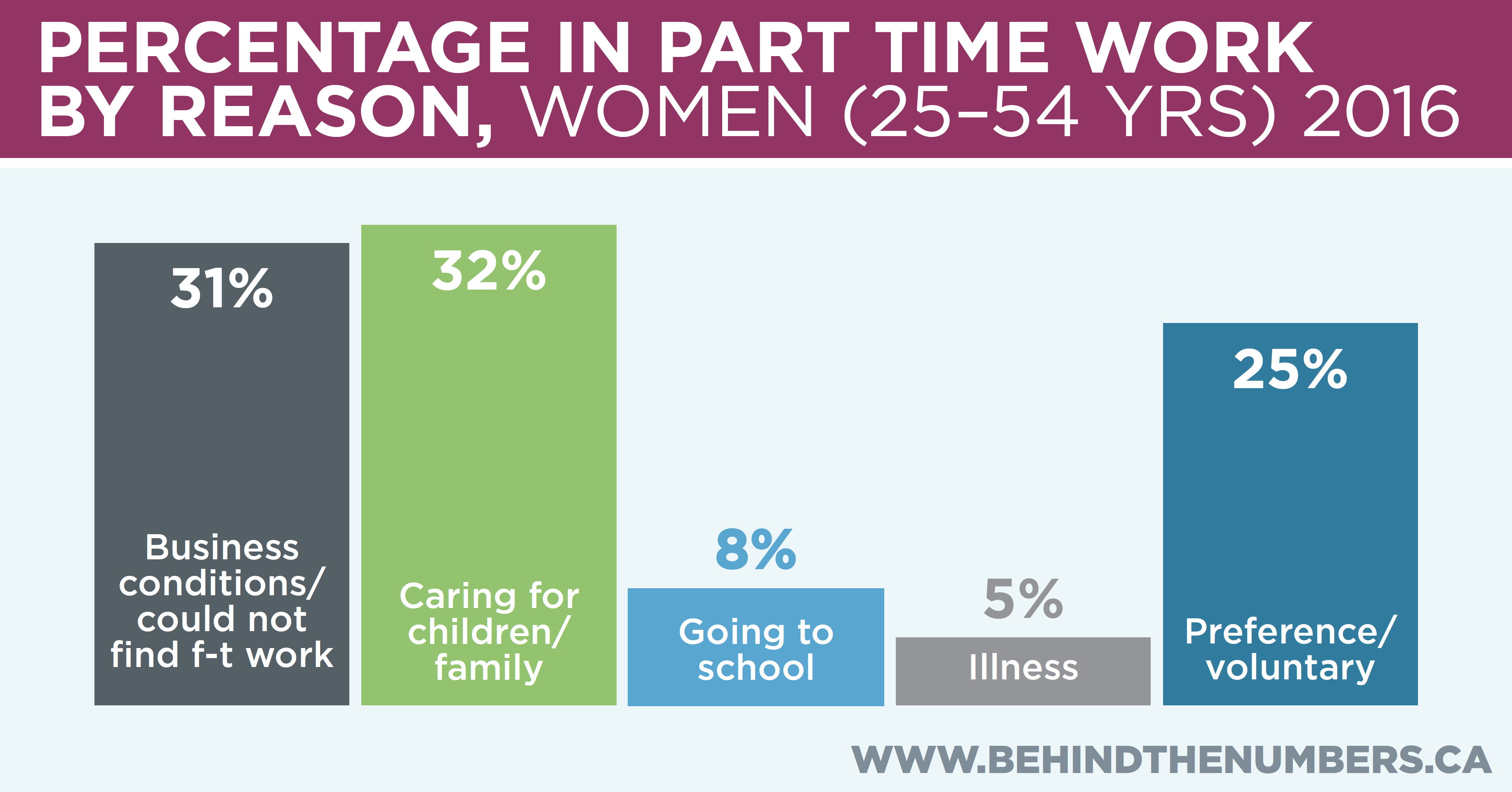

Women are twice as likely as men to work part-time. The majority of those women (63%) are involuntary part-time workers. Half of those involuntary part-time workers cite childcare as the reason they are not in full-time work and half cite business conditions.

Affordable and available childcare has had a demonstrable positive effect on women’s employment levels and on the wage gap in similar high-income countries. However, long waiting lists and high fees are leaving 275,300 women in involuntary part-time work. As a recent study points out, outside of Quebec, the cost of childcare means that net all tax and other benefits “the household’s economy clearly worsens if the mother enters the labor market.”

The share of women who cite business conditions as the reason for part time work suggests that we are lacking both sufficient investment in the sectors where women work and that it is employers, not female workers, who need further incentives to lean in.

4) Shift the balance of unpaid work

Women perform 10 more hours of unpaid work per week than do men. They perform more total hours of work (paid and unpaid) than do men. (But who’s counting?) The disproportionate share, particularly of childcare, limits the number of hours available to women to do paid work. It also makes it more difficult for women to enter occupations with non-traditional or inflexible hours. You know, like politics.

Affordable and accessible childcare is essential to shifting the balance of unpaid work for women. However, stand-alone paternity leave has also been demonstrated to play an important role in redistributing hours of unpaid work. The Quebec Parental Insurance Program, which provides five weeks of ‘father only’ leave has resulted in 78% of men now taking parental leave in Quebec, compared to 27% in the rest of Canada. Or maybe men in Quebec just love their children more? (I don’t think so).

5) Invest in women’s organizations

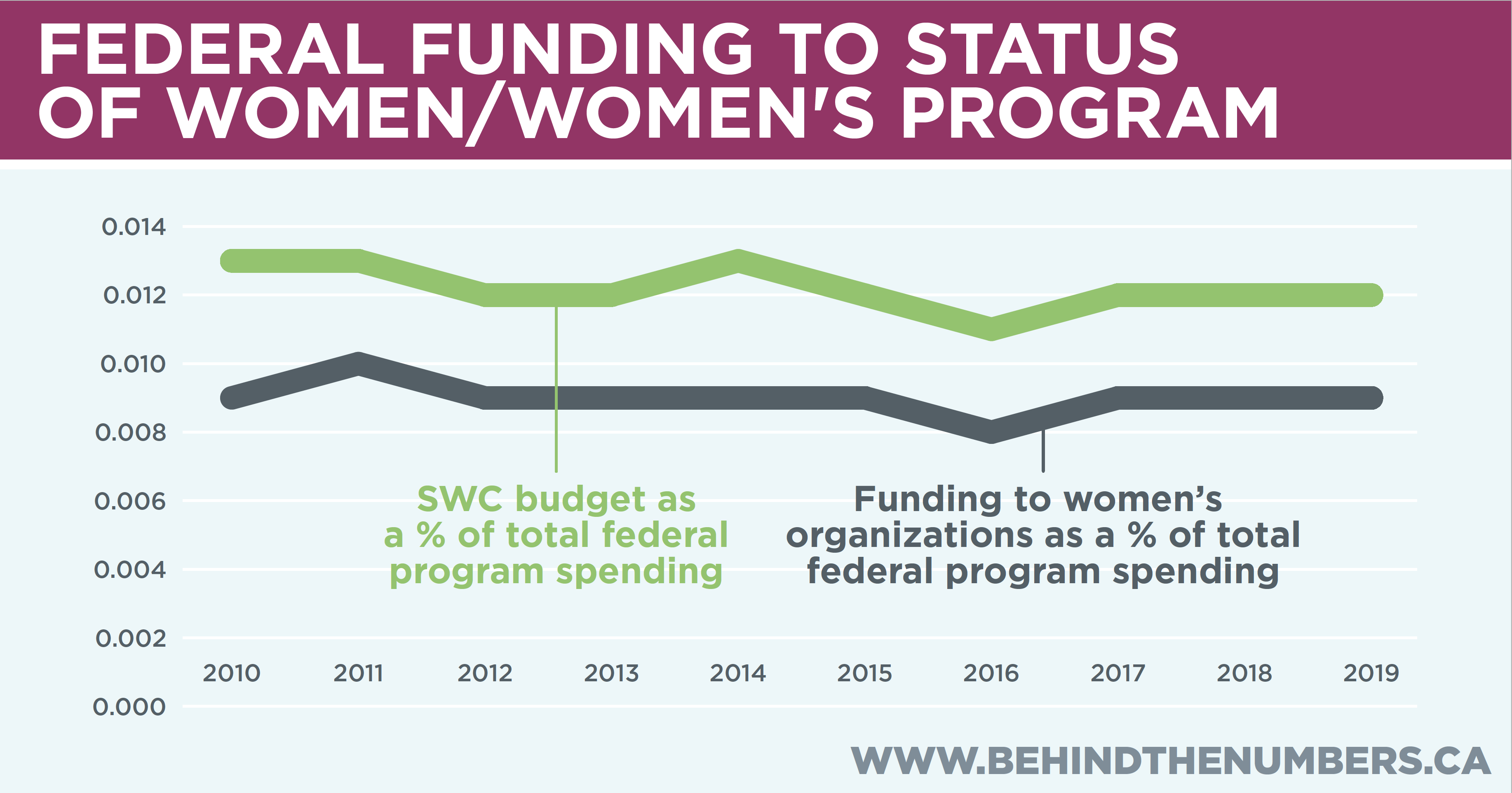

It isn’t just me; research has demonstrated that women’s organizations make an essential contribution to ensuring that public policy works for women. Yet federal funding to women’s organizations has actually decreased under the current government.

That direct federal funding of women’s organizations continues to represent a miniscule proportion of the budget – less than one one-hundredth of one percent of total federal program spending.

I like to point this out every time I find myself sitting at a table in a Government of Canada building with a group of women’s organizations offering (free) expertise and research. Consultation is great, if you have someone to consult with.

6) The economy needs women

Under-employing and underpaying women is costing women and the economy billions of dollars annually. The International Monetary Fund estimates that if the employment gap between men and women were closed, our GDP could go up by 4%. If the 670,000 women who were working part-time for non-voluntary reasons in 2016 were able to find full-time work, they would have brought home an additional $19.2 billion in wages. If the women who worked full-time last year earned the same hourly wage that their full-time male counterparts earned, they would have taken home an additional $42 billion.

The 2017 Federal Budget gender statement was an important first step in making the most of both halves of Canada’s labour force. However, core economic policies need to address the fact that men and women work in different occupations, at different rates of pay, for different numbers of hours. Moreover, targeted policies need to address the additional barriers that face Indigenous women, women with disabilities, immigrant and racialized women – all of whom see larger than average gaps in pay and employment.

The women are out there. They are educated and in the labour force. Don’t make them the keepers of their own disadvantage. They don’t create hostile work environments; they don’t discount their own pay; they don’t set childcare fees. Women need their governments and employers help in removing these barriers.

Time to start leaning in gentlemen.

Kate McInturff is a senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.