The need for a more just food system that nourishes both people and planet has never been more evident.

Most of us get our food from the fossil fuel-dependent industrial food system, controlled at every step by large corporations. It produces unfair and unjust differences in health between groups of people depending on who has (or does not have) power, influence, and resources. And it is failing us on multiple fronts.

For example, there are millions of people who don’t have enough food to eat. People working within the food system are often exploited and mistreated. And food system activities contribute significantly to the climate crisis as well as water and soil pollution.

A healthier, more sustainable, fairer food system is needed. But how do we get there?

Everyone who wants to help build a better food system for the future needs first to understand the current one—how it’s organized, who is involved, and how and why it produces the unfair outcomes it does.

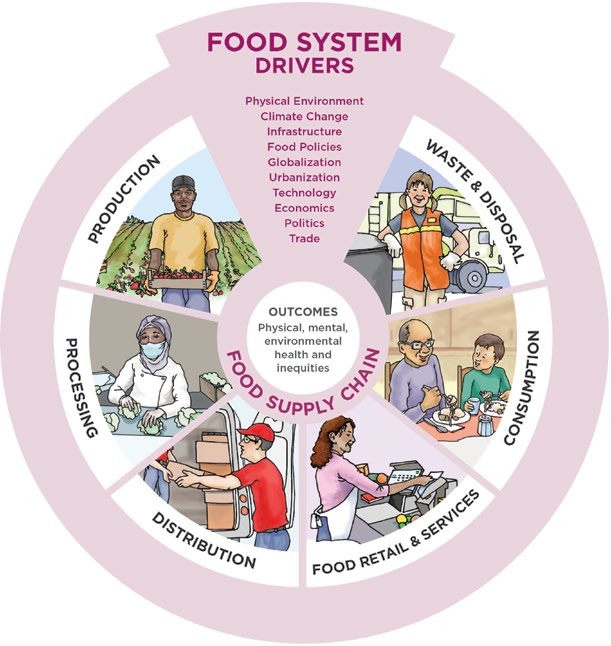

We can think of the food system as consisting of three major components: (1) food supply chains; (2) people and institutions; (3) and drivers and outcomes.(Parsons, K, Hawkes, C, Wells, R, 2019)

Food supply chains are the stages food goes through from where it is produced to where it is consumed and wasted. This includes production, processing, distribution, retail, consumption, and waste.

People and institutions are involved at all stages. These include suppliers, farmers and other growers, food processors, distributors, food services, supermarkets and waste management companies. Ultimately, because we all eat food, we’re all part of the food system.

Food supply chains are shaped by drivers, including food policies enacted at all levels of government, physical environments, the climate crisis, and wider processes like globalization.

These drivers interact with the activities and people involved in the food supply chain to result in physical, mental, and environmental health outcomes for both food system workers and consumers.

“The current industrial food system is neither healthy, sustainable, nor just.” (NCCDH, 2024, p. 12).

Consider migrant farm workers who come from countries like Mexico and Jamaica through the federal Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program to work in fields, orchards and more. They’re essential to feeding the population, yet they’re denied the health and safety protections they need.

For example, many migrant farm workers have expressed concerns about substandard housing (i.e., crowded, unsanitary conditions), a lack of safety equipment, and being discriminated against by their employers. They’ve also reported being denied medical care, just as their wages are very low and unreflective of the back-breaking work they do to keep the food system going.

Underlying the poor treatment of migrant farm workers is a profit motive—a desire to keep costs of food production low to maximize profits—and, critically, an insidious belief that migrant farm workers are undeserving of fair wages and decent work conditions.

How we treat migrant farm workers in this country is a prime example of how food systems produce inequitable health outcomes. Another is the immense influence the corporate food industry has in creating food environments lacking in nutrients but abundant in nutrient-poor ultra-processed foods.

Corporations—think big food and drink companies like Coca-Cola, Nestle and Kraft Heinz—engage in tactics to make sure food policies benefit their for-profit interests and allow for continual growth and dominance. This ‘playbook’ includes direct government lobbying, financial incentives for policy-makers, and pushing for voluntary self-regulation as a substitute for government intervention (Moodie, 2021).

Ultimately, these tactics don’t affect all population groups equally. Black and other racialized youth, for example, are inundated with advertisements for ultra-processed foods, like salty snacks, sugary drinks and cereals, at higher rates than other groups of young people.

None of this is good. But what will it take to shift these inequities?

With a better understanding of the current food system, we can then dream of alternatives as proponents of food justice have done: imagine what a healthier, more sustainable, and just food system could look like.

Let’s think about the transformative power of food justice

Food justice recognizes food as a human right, not a commodity. Food justice is holistic, centering the people who are most impacted by food system inequities and focused on dismantling the forces that put people at risk of poor health at all points in the food supply chain. It centres racial equity and stands in solidarity with justice in other areas, including workers’ rights, climate justice, housing, income, and protection of natural resources.

We need to envision and create a food system that is ‘just’. Where people are prioritized over profits, natural and physical environments are cared for, and everyone can live healthy and dignified lives according to their needs.

Who gets what?

In a just food system, everyone has equitable access to nourishing, affordable food and the resources needed to produce food. Food is culturally relevant, access is dignified and self-determined. Workers receive fair and livable wages, labour practices ensure benefits and protect against discrimination. This is distributive justice.

How are decisions made?

In a just food system, power is redistributed from corporations to communities, who then make decisions about the design and functioning of their food systems, identifying opportunities for transformative change based on their knowledge and experiences. Community members contribute meaningfully to decision making about where they get food and how food is produced. This is procedural justice.

Who counts?

In a just food system, diverse food knowledges of communities are central to food system planning. The traditional ways people produce and consume food are respected, as are their collective ideas and needs. Actions are taken to correct historical and current harms that contribute to food inequities. This is recognitional justice.

So how do we make distributive, procedural and recognitional justice a reality for everyone?

We might work with municipalities to ensure principles of justice and equity are embedded in the bylaws that support local food production and food purchasing contracts.

We can also work with others to link food-growing efforts to affordable housing development.

What’s more, we can develop meaningful relationships with grassroots organizations and support them in their efforts to influence policy through financial support and other resources.

We can also promote the rights of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples to make decisions about their own food systems.

Food justice is more than the outcome—it is also about the process.

We can build a food system that is different. One where equity and human rights are considered at all levels; where production processes don’t hurt the earth; where workers are treated fairly; where traditional knowledge and customs are respected; and where nourishing foods are available to all.

This article is based on the following products from the National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (NCCDH):

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. (2024). Determining Health: Food systems issue brief. Antigonish (NS): NCCDH, St. Francis Xavier University.

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. (2024). Determining Health: Food justice practice brief. Antigonish (NS): NCCDH, St. Francis Xavier University.