Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

It’s only been a couple of weeks since Disney, that most iconic of American companies, moved to displace all its home grown techies with low-cost foreign temporary workers. But the company had to beat a hasty retreat in the face of an outpouring of criticism.

Amid the deluge of commentary this story triggered about where America is headed, blogger and finance professor Noah Smith turned his eyes north and gave Canada a mighty shout-out in a column for Bloomberg, Canada: Tomorrow’s Superpower.

Professor Smith rightly pointed out that, among the attributes that will make any nation great in future, immigration policy is key. But in his haste to explain what’s right about Canada’s policies, he skipped over the part of the story where we’ve begun to ape what’s wrong about the American way: a growing reliance by business on temporary “guest” workers.

Canada’s immigration reforms have pivoted from family reunification to economic immigration, with a focus on new permanent residents who have high educational skills and/or high net worth.

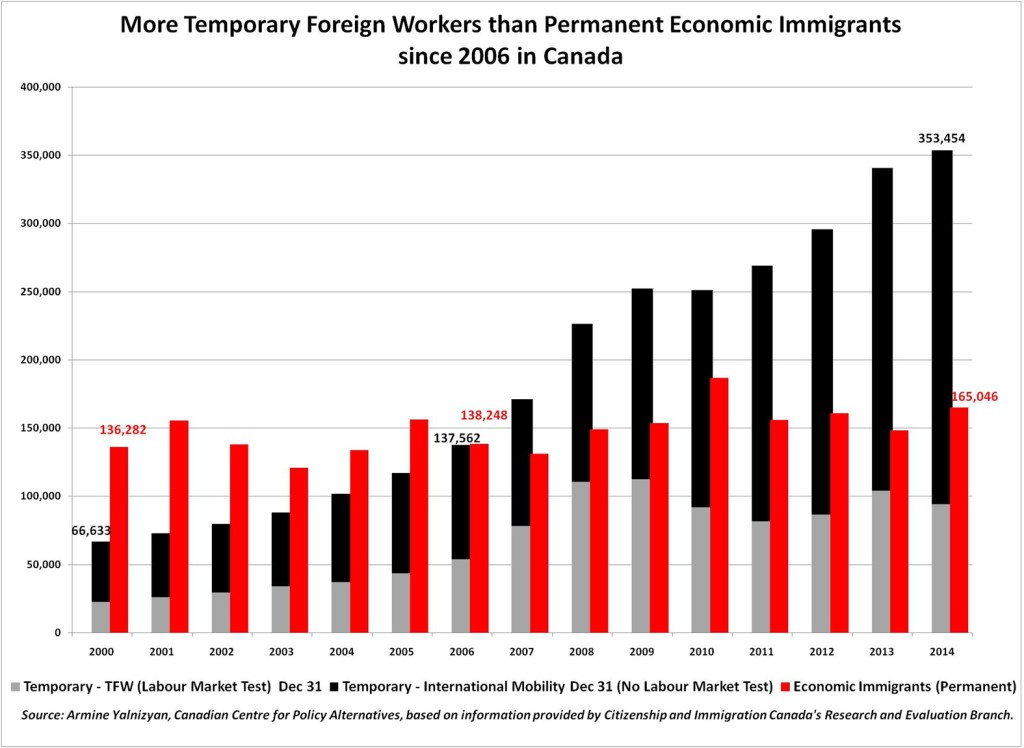

What most people don’t realize is that our intake of foreign workers has almost doubled since 2006—right through the recession, amidst rising unemployment rates, and with no recovery for young workers. But almost all of the net new growth is driven by the escalating use of temporary foreign workers, not permanent economic immigrants.

Canadian businesses have turned to these workers for a variety of reasons, including legitimate shortages in certain pockets of the labour market, inadequate workplace training, and a desire to cut costs.

The Disney story that so riled Americans is almost a perfect mirror image of a 2013 story that alarmed Canadians about practices at the Royal Bank of Canada. We’ve since learned the hiring of temporary foreign workers is a routine thing at Canadian banks and far beyond the finance sector.

The distinction between policies that encourage permanent or temporary newcomers is critical to Canada’s future and the future of a world dogged by population aging.

All the advanced industrialized nations are aging. Japan is first, but South Korea and China, and virtually every European country, are right behind. Canada is among the most rapidly aging societies because of our relatively large postwar baby boom.

Our labour shortages, now limited to booming pockets of the economy, will become endemic as baby boomers retire in droves, which will happen long before the robots take over. In the meantime, economic migrants are becoming the tail that wags the dog of economic development and the evolution of nations.

Recently, the UN Refugee Agency noted that 59 million people were displaced in 2014 by violent conditions where they live, the highest number of displacements on record, and the fastest single year of growth. These numbers do not include the displacement of peoples because of climate change, which is a growing phenomenon as well. Nor do they include rising numbers of international students and professionals who go abroad to seek greater opportunity.

Pushed or pulled, people are on the move as never before. So is capital.

For the last three decades, nations have tried to become magnets for money, in the hopes of drawing investments that create growth and jobs. For the next three decades, nations with aging populations will need to be magnets for both capital and labour, just to maintain standards of living.

The stakes are high. We are establishing the terms of the game for decades to come, for migrant workers and citizens alike.

There is perhaps no more fundamental test of policy success or failure than how labour force needs will be met in the coming years.

Will newcomers be invited in as “guest” workers or as citizens-in-the-making? This is a new issue for Canada, and an increasingly contentious one.

Numerous policy announcements meant to quell concerns have done little to change the trends. No one has answered the core question: Why are temporary foreign workers good enough to work, but not good enough to stay?

Professor Smith is right—Canada has the potential to become a superpower, a country the world regards with respect and envy for its economic, social and political strength.

But it won’t get there by relying on the permanently temporary.

This piece was first published in the Globe and Mail on July 6, 2015 (July 7 print edition).

Armine Yalnizyan is a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, and business columnist for CBC Radio’s Metro Morning. You can follow her on Twitter here.