Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

There was a point in 2016 when it seemed the Canada–European Union free trade deal – CETA – was not going to make it. Ironically, Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States has all but assured its approval in Europe.

Resistance to CETA, which had been building quietly in Europe for several years, exploded into massive street protests in Germany and Brussels in the middle of 2016. The lightning rod was the inclusion of rights for investors to challenge public policies that harm their profits.

But other parts of CETA were rightly criticized for how they would weaken the precautionary principle and undermine public services. These concerns, and studies showing the agreement would suppress wage and job growth on both sides of the Atlantic, should have sucked the air out of any promises of a new, sustainable trade regime.

And yet, in this upside-down post-Trump world, an agreement that will contribute to widening inequality is being spun, impossibly, as a victory for progress. An agreement negotiated by Stephen Harper’s government (one of the most right-wing Canada has ever seen) on behalf of, and with input mainly from, very large corporations, will be declared a major boon for the struggling middle class.

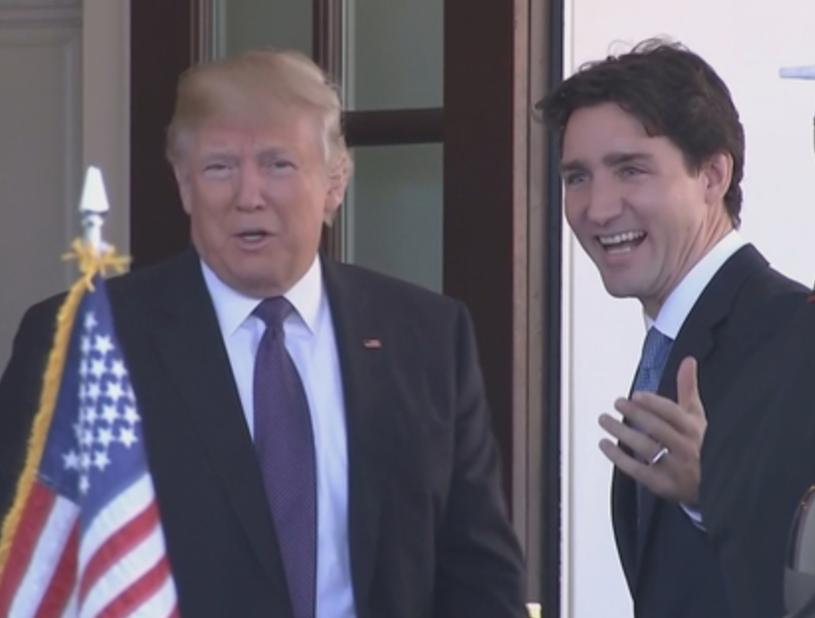

Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, plans to be in Strasbourg next week for the European parliament vote – to give CETA a final Midas touch that will transform it from political hot potato to “gold standard” trade deal. Unfortunately, in its current form CETA will only fuel Trumpism and its European variants on the far-right.

Despite some last-minute procedural reforms, CETA will eventually expose European regulations to more investor lawsuits from Canadian resource firms and the Canadian subsidiaries of U.S. multinational corporations, ushering in, through the back door, a hated part of TTIP, the supposedly moribund EU-U.S. free trade deal. CETA also advances a long-standing North American demand for “regulatory cooperation,” a euphemism for an early warning system that allows foreign corporations to nip unwanted regulations in the bud. The election of Trump, who is already unleashing a deregulatory tsunami in the U.S., only heightens the threat this new framework poses.

Far from acting as a counterweight to Trump, the Canadian corporate sector is already pressing the Trudeau government to match the U.S. president’s deregulatory moves in order to remain competitive in their most important market. CETA’s regulatory cooperation mechanisms will provide an avenue for North American lobbyists to quietly deploy downward pressure against EU regulations. This is particularly true in sensitive areas such as genetically modified organisms and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, where Canada and the U.S. have continually challenged the EU diplomatically and at the World Trade Organization.

CETA also fails to live up to its “gold standard” hype for what is missing from the agreement. Despite what the European commission says about its hastily cobbled together “understanding” on CETA, the text contains no valid general carve-out for public services, which are shielded from CETA’s powerful investment and services obligations only grudgingly and in a piecemeal manner.

On our side of the pond, CETA forces Canada to change its patent protection system in ways that are expected to add $850m a year to the costs of medications. Canadians already pay the second-highest drug costs per capita in the developed world. CETA’s stricter intellectual property rules will more than cancel out the potential benefits to Canadian consumers of tariff elimination on all EU imports into Canada.

As Thomas Piketty and others have highlighted, the Canada-EU deal also contains no binding targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, CETA hardly mentions climate change at all. Its protections for labour, the environment and sustainable development are essentially toothless. European social democrats should be ashamed to endorse them, let alone portray them as a victory for workers.

Environmentalists, consumer advocates, trade unions, political progressives and many small- and medium-sized enterprises, on the other hand, are right to ask the European parliament to block this Canadian deal. With CETA the idea of “social Europe” – the co-operative, progressive counterpoint to a union organized primarily for the benefit of transnational capital – recedes further into the imagination.

The rebranding of CETA as a progressive, “gold standard” agreement is hardly an antidote to the frightening resurgence of right-wing nationalism that preys on the inequalities and insecurities created by the type of globalization that is codified and enforced in CETA’s two-dozen chapters. It is precisely that type of self-serving spin that fuels public cynicism and anger at liberal elites.

If one of the lessons of the Brexit vote and election of Trump is that too many citizens feel they are losing control over their lives and economic futures, then sleepwalking into a trade deal that will cede even more democratic authority to the corporate sector is playing with fire.

Scott Sinclair is Senior Trade Researcher with the CCPA. Stuart Trew is Senior Editor of the Monitor, the CCPA’s bimonthly magazine of progressive news and opinion. They are the co-editors of the book The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Canada: A Citizen’s Guide (Lorimer, 2016). This article first appeared in the Guardian U.K.