On March 17, Ontario Premier Doug Ford declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, mandating the immediate closure of everything—from recreation centres and public libraries to restaurants and bars—until March 31.

Prohibiting public gatherings of 50 people or more, the Ford government also shared a breakdown of a $304 million relief package. Among other things, the package will fund 575 more critical and acute care beds, 25 more COVID-19 response centres, and $50 million in new personal protective equipment for frontline workers.

As of March 18, 198,000 cases of COVID-19 exist in over 100 countries, with more than 598 cases in Canada and 198 in Ontario. Given the severity of this crisis, with eight deaths in Canada so far, the government’s actions are welcome.

Unfortunately, the premier’s announcement comes at a time when the vital work of frontline health care workers has been severely underfunded—and undervalued—for some time.

Nowhere is this more obvious than with respect to nurses.

Ontario’s systemic underinvestment in nurses has led to a shortage of nurses and resulted in employment patterns—part-time jobs, temporary jobs, multiple jobs—that not only hurt nurses, but hurt all of us.

We remain in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. We know that nurses are taking on dangerous and frightening work. Unfortunately, they are working in a health care system that has been drained and strained by austerity measures since long before COVID-19 came along.

You get what you fund

Ontario governments have a record of underinvesting in health care. Between 2011-12 and 2016-17, health care spending grew at an average annual rate of 2.2%, far below what was needed to maintain existing services. From 2018-19 to 2019-20, the increase was 4.4%, still far short of the average 6.8% growth in spending in the 10 years prior to 2011-12.

Last year, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) produced updated estimates of the funding that would be required to maintain Ontario’s existing health system. It projected the impact of the core cost drivers: population growth, population aging, and inflation in health care expenditures. To maintain services at current levels, the FAO found, would require health spending to increase by 4.6% per year.

The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) recently released a report describing how thinly resourced the hospital sector is in Ontario. The OHA reported that if Ontario’s per capita hospital spending reached the average of Canada’s other provinces, we would be spending an additional $4 billion per year, and health spending overall would be an additional $4.6 billion per year. A telling statistic cited in the report is that Ontario is tied with Mexico for the fewest acute care beds per capita of any country tracked by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

The Ford government’s current plans would continue to underfund the health care system. The 2019 fall economic statement projected health spending to increase by 2% in 2020-21 and 1.1% in 2021-22. The promised $304 million in additional funding, while welcome, is a drop in the bucket: it will not bring sustainability to the health care system.

Lessons from SARS

When Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) hit in 2003, 44 Ontarians died. Some of them were nurses.

In the 1990s, again in a context of funding cuts, nurses’ jobs became increasingly precarious. Just-in-time staffing resulted in more part-time and casual staff, fewer full-time nurses, and an increasing reliance on agency nurses and overtime.

During SARS, the results of these funding cuts meant higher costs, reduced surge capacity, nurses working overtime for multiple employers, and stress-related absenteeism. Ultimately, nurses and patients both suffered.

The recommendations from the SARS Commission to safeguard nurses’ and patients’ health during an outbreak included that:

- the health concerns of health workers must be taken seriously;

- the “Ministry of Health would be well advised to listen more carefully to the reasonable concerns of health worker unions” (p. 40); and

- stronger occupational health and safety protections are needed for health workers.

The Ontario Nurses’ Association conducted a survey for the SARS Commission. The results were stark: 58% of nurses said their health and safety had been compromised during the outbreak, and three-quarters were unaware of any Ministry of Labour worker protection activity at their workplace.

The depleted RN workforce

Italy, where more than 3,000 people have died due to coronavirus, has experienced a stark shortage of nurses and health care workers due to health workers becoming infected with COVID-19.

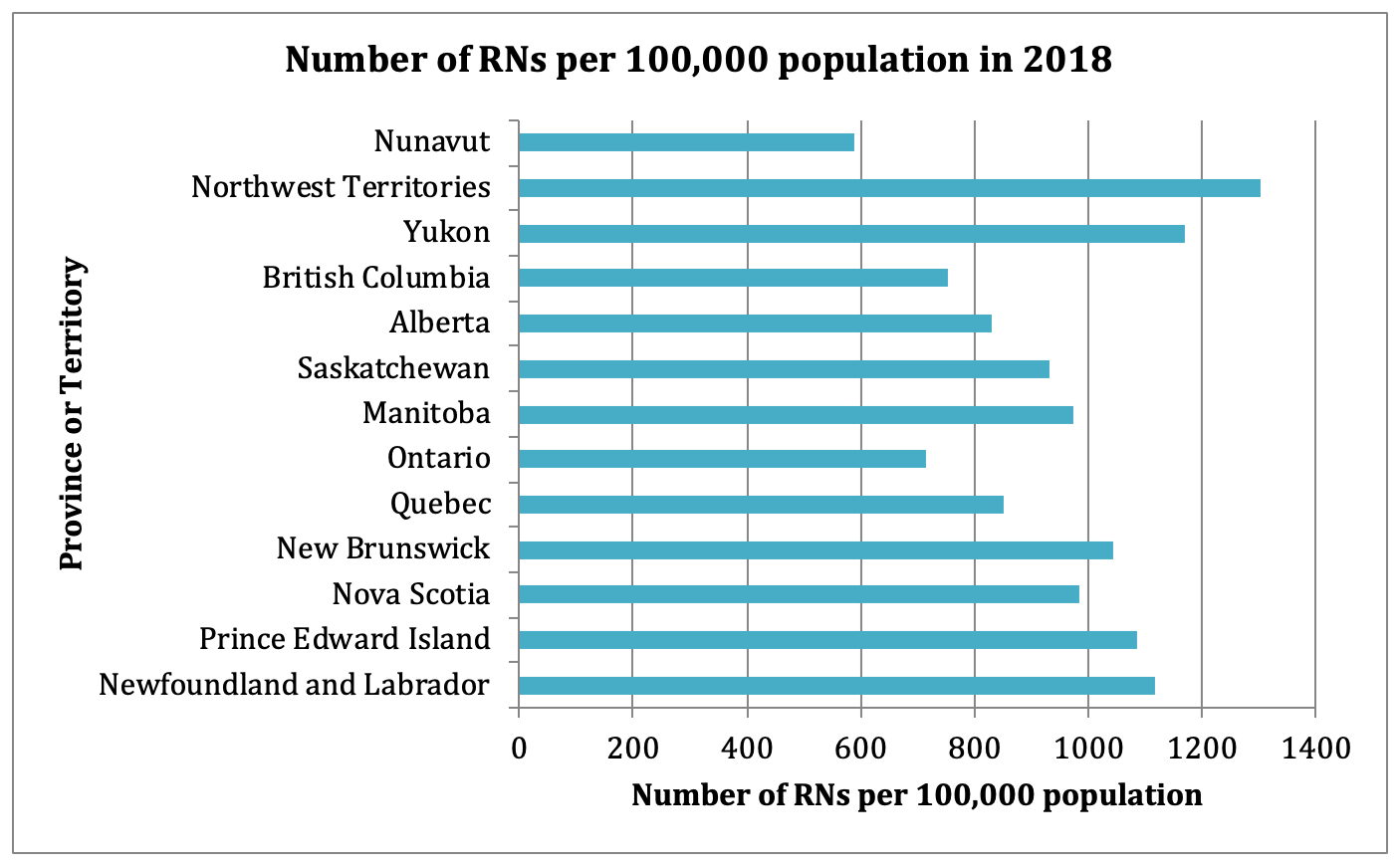

In Ontario we have entered this pandemic with a significant RN shortage. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) estimates that the number of RNs in Ontario dropped from 106,889 in 2011 to 102,396 in 2018. Ontario has the lowest RN to population ratio in the country. The following chart shows the number of RNs per 100,000 in 2018 by province or territory.

Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information

Rise in precarious work for RNs

Austerity policies have had a negative impact on the number of RNs in our health care system, as well as on their working conditions. Precarious employment is characterized by reduced job security, stability, lower income and fewer benefits. It has been on the rise in Ontario. While much precarious work is concentrated in low-wage, so-called lower-skilled occupations, there is a growing awareness of precarious employment in professional sectors.

Precarious work has a number of negative health impacts including those associated with stress, uncertainty and lower incomes. This should be a concern in and of itself. But we also know precarious work for RNs can have a negative impact on their patients. It seems like the lessons from SARS are being forgotten.

Perhaps most importantly, in light of the current pandemic, many part-time and temporary nurses have no health benefits—and no paid sick leave. Notwithstanding the recommendations of the SARS Commission, many may still feel pressured to come to work sick.

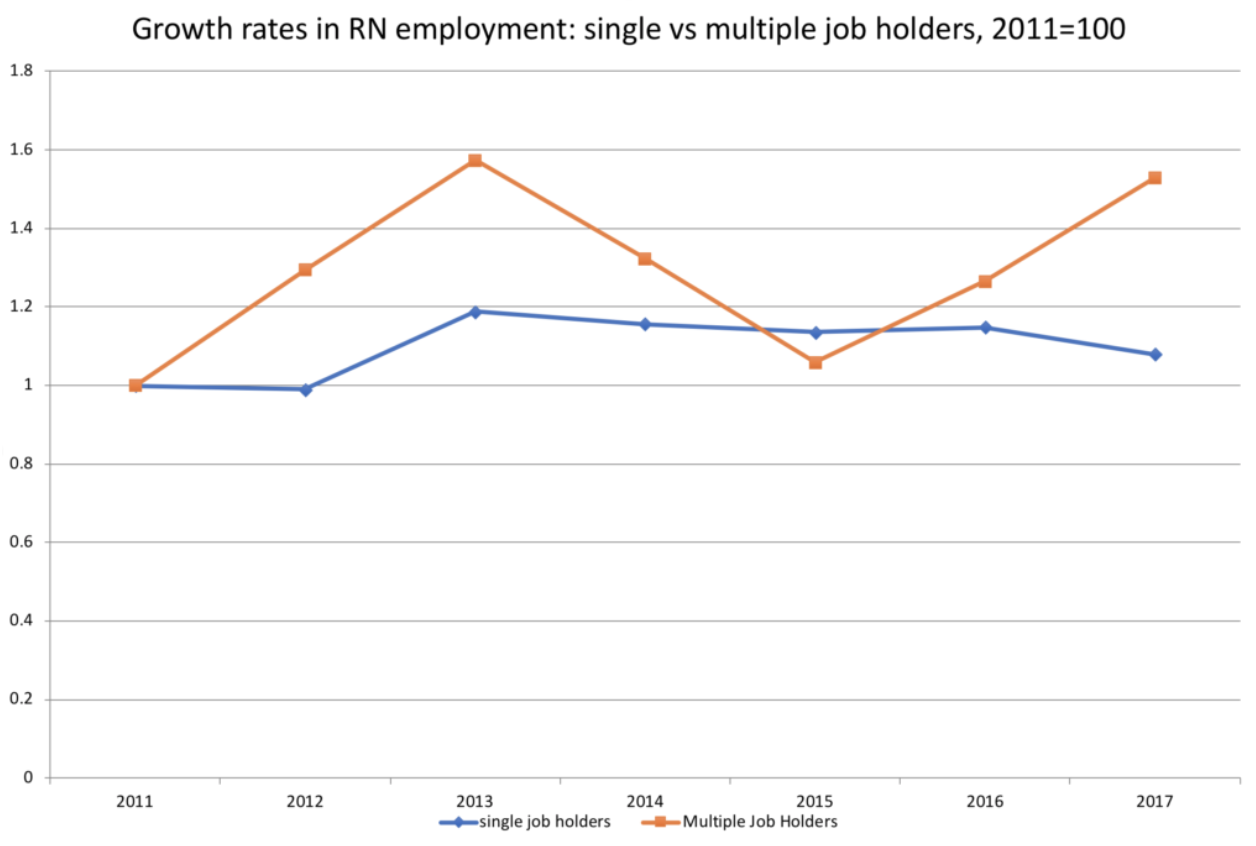

Special tabulations from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey show the trends of increased precarity in RN employment associated with a period of austerity from 2011 to 2017. The chart below shows the pattern for multiple vs. single job holders. While RNs with multiple jobs remain a small share of the total, they are growing more quickly than single-job holders.

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Special Tabulations

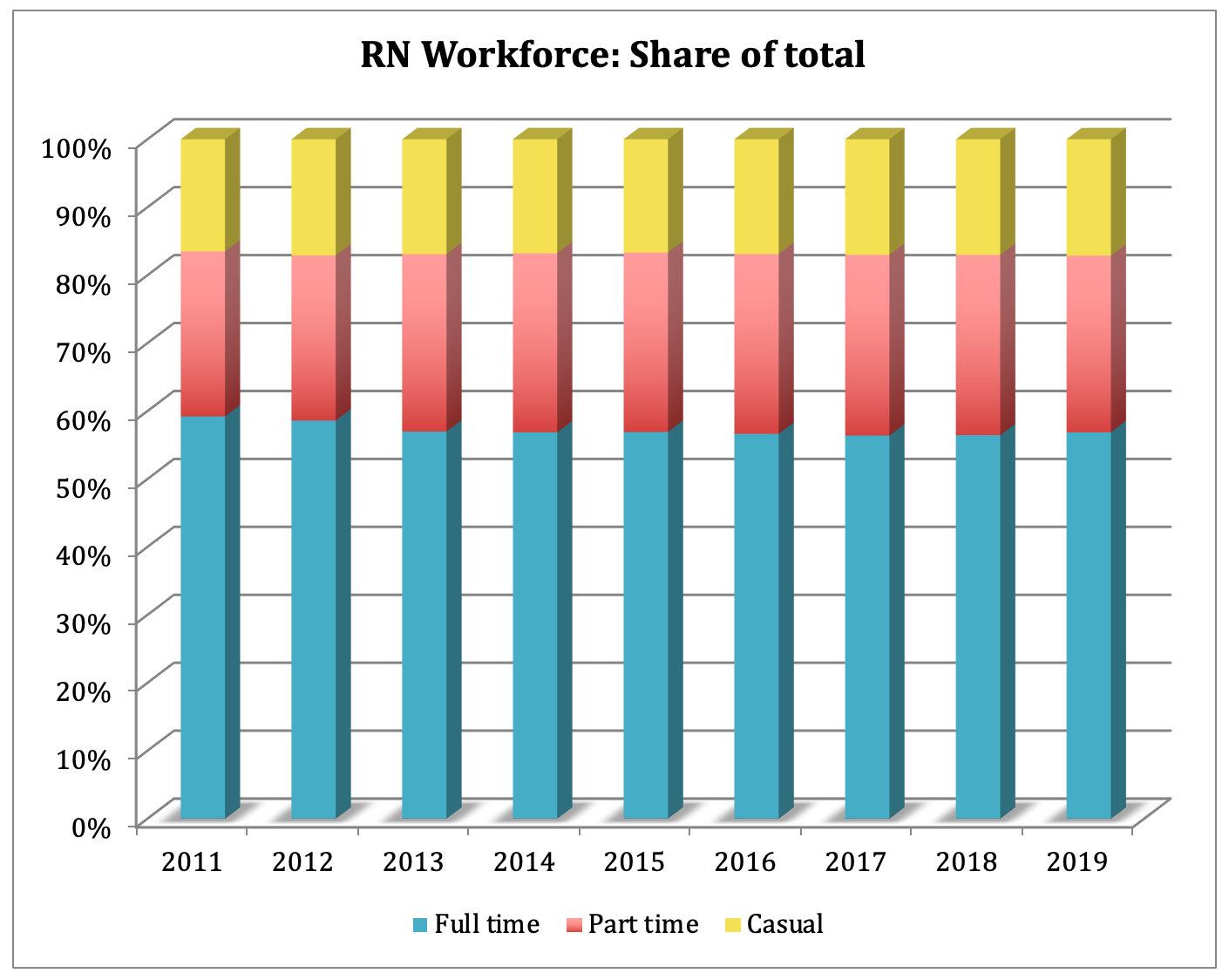

This next chart shows the distribution of RN positions between 2011 and 2019. It illustrates the shift from full-time to part-time positions over this period. Full-time positions dropped from 59.2% of the total to 56.9%, while part-time positions rose. The chart also shows a slight increase in the share of casual positions, from 16.5% to 17.1%.

Source: College of Nurses of Ontario

We have a wealth of data and insight from nurses who were at the frontlines of SARS. Hindsight is 20/20; foresight is a gift. Both are telling us that Ontario must meaningfully invest in nurses if we are committed to avoiding unnecessary deaths in the midst of a global pandemic.

Simran Dhunna is a CCPA placement student and MPH Epidemiology candidate at the University of Toronto. She is also an organizer with Climate Justice Toronto and Peel. Sheila Block is Senior Economist with the CCPA-Ontario.