Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

With consultations starting up again this week, the special advisors for Ontario’s Changing Workplace Review would do well to look at two new developments in U.S. labour markets.

The first is a move by a number of major retailers to end on call scheduling. It requires workers to be available to work, but does not guarantee that they will be called in and provides no compensation for requiring them to be available.

Technological advances in scheduling software have made this practice more widespread.

On call scheduling has a number of negative impacts. It means you don’t know how much you will earn from week to week, it limits your ability to work at other jobs, and it creates a great deal of uncertainty for family life (for instance, do you arrange for child care in case you are called in? If you aren’t, how do you pay for that child care?).

These major retailers didn’t just wake up one morning and decide that they needed to be better employers.

There has been concerted organizing to improve working conditions for low-wage workers from organizations like the National Employment Law Project.

A number of state governments have proposed legislation to end on-call scheduling.

Finally, improving labour market conditions in the U.S. are also putting pressure on employers to improve working conditions.

Variable hours of work don’t stop at the border. We know that many low-wage workers in Ontario face a great deal of uncertainty about their working hours.

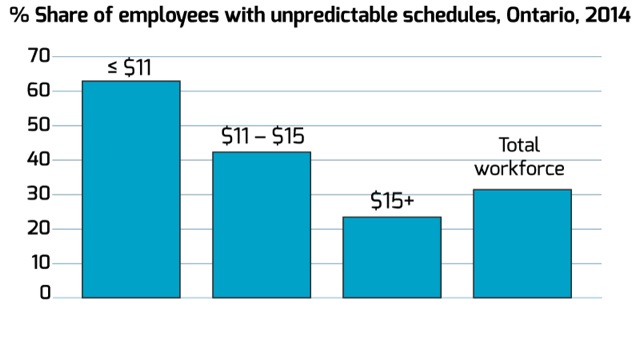

In 2014, 63 per cent of minimum wage workers in Ontario had jobs where their hours varied from week to week. In other words, unpredictable hours are the norm for most minimum wage workers (six in 10) in Ontario today.

The situation is slightly better for those earning between $11 and $15 an hour: 42 per cent of those workers had hours that varied from week to week. But it still means four in 10 workers earning between $11-$15 an hour can’t rely on predictable work hours. In sharp contrast, only 23.4 per cent of workers who made more than $15 an hour had variable hours.

Changes have been proposed to the Employment Standards Act would address this issue. They include: two weeks’ advance posting of work schedules, requiring employees to receive compensation if schedules are changed within that two-week period, and protection from reprisals if workers request a change in schedule.

There is also progress being made on the issue of unpaid overtime in the United States. President Obama is updating regulations on eligibility for overtime pay. Currently, if you classified as a manager and you make more than $23,660 (U.S.) a year — below the federal poverty line for a family of four — you aren’t entitled to overtime pay. The proposed change would more than double that threshold. It will have a particularly positive impact on managers in the retail and restaurant industries.

The rules about overtime differ between the U.S. and Ontario. However, there is a similarity in that managers and supervisors are not eligible for overtime pay.

That can be justified for middle managers whose median earnings are more than $40 an hour. But supervisors in food services with median earnings of $12.50 an hour and in retail with $15 an hour in median earnings should be eligible for overtime.

The proposal to repeal overtime exemptions and special rules would address this issue.

Ontario can mirror these progressive changes in U.S. labour market policies. These changes would make immediate, concrete improvements in the lives of low-wage workers and their families.

Sheila Block is senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Ontario office (CCPA-Ontario). Follow Sheila on Twitter: @SheilaBlockTO.