“The Eurozone Summit of October 27 saw the first three steps: a “haircut” imposing losses of 50 percent on creditors who own Greek government debt: a recapitalization of Europe’s banks, to the tune of €106 billion: and an extension of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). Further down the road, some sort of federalization of European debt is surely inevitable. The likely step involves the creation of a eurobond, so that governments can borrow on a continent-wide basis, with continent-wide guarantees of security.”

– John Lancaster, “How We Were All Misled,” The New York Review of Books, Dec. 2011

Outline of the Dilemma

European problems seem to hit the headlines each day. These problems, largely of debt and deficits, will affect every country including Canada. The main questions are within the Eurozone, those countries that have a common currency, the euro. The seventeen countries are Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.

The variety of these countries has pointed out all the problems with a common currency and a common central bank but with no common fiscal arrangement. With a common central bank these countries have no independent monetary policy nor do they have the ability to devalue their own currency as long as they remain within the Eurozone of euro currency. Their government debts and private debts are in euros, which mean that if one country were to move out of the Eurozone and set up its own currency and devalue, the debts would remain in euro currency and the problems of repayment would be exacerbated.

This analysis points out that Europe’s problems are not just the size of government debts and deficits but also a problem of a common central bank. With the diverse set of country economies the European Central Bank (ECB) has much broader responsibilities than any of the former national central banks. We are questioning whether the ECB has been sufficiently active in taking on these diverse responsibilities. But finally, just before Christmas, the ECB began to move. They announced the availability of three-year-term loans to the banks of the Eurozone region.

While the headlines suggest Europe’s debt crisis is deepening, it is hoped that Eurozone technocrats are working on the details of a euro bond scheme to give the euro governments some much needed time to hammer out other details.

Similarly, despite ongoing political wrangling in Washington on the U.S. debt front, the world’s largest economy continues to grow.

Still, the Eurozone remains at the center of the financial storm, and the responses from the European Central Bank (ECB) and Germany (the largest and the most fiscally stable economy in the bloc) though sometimes hopeful often disappoint markets and exasperate just about everybody else.

The numerous fiscal austerity programs now in place will surely tip the Eurozone into recession. Unfortunately, slower growth in the region will spill over to its trading partners, and Britain will be lucky to avoid a hard landing as well.

The longer Europe dithers in solving its debt crisis, the steeper we can expect the looming recession in the euro area will be. As well, if the worst case scenario occurs in Europe – namely, declining output together with increasing unemployment — then the austerity programs designed to reduce government deficits will not only be unpopular, they will also fail.

The Eurozone economy expanded at less than a 1% annual rate in the third quarter and it will likely contract in the final three months of the year. Even Germany, the strongest economy in Europe, is starting to falter as industrial orders weaken and manufacturing activity slows. Germany’s economy expanded at a 2% annual rate in the third quarter.

The ECB Has Been Far Too Timid

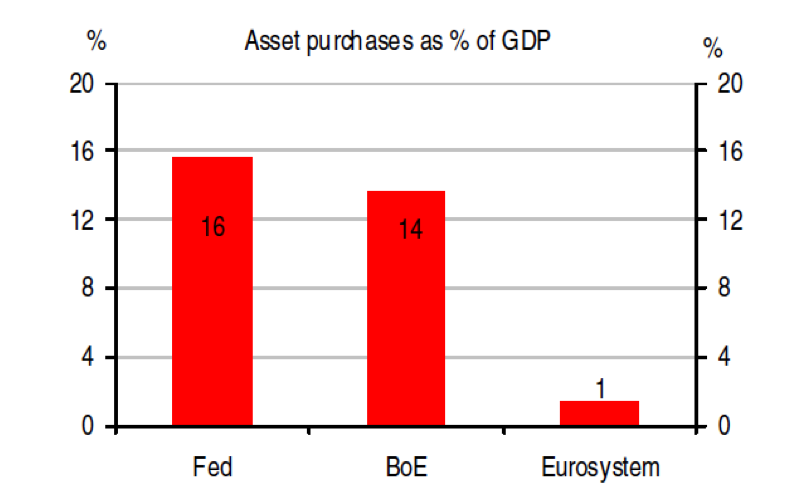

As the following two charts illustrate, the ECB has been far less generous to its financial stakeholders than its American and British counterparts.

For example, the ECB balance sheet has expanded far less than the comparable central bank balance sheets in the United Kingdom and the U.S. In fact, the expansion rate of the ECB’s balance sheet levelled off at the end of 2008, though there has been some new expansion in November and December in the wake of the latest crisis phase.

The ECB’s relatively modest support of the financial markets can also be seen in its relatively small bond purchasing program — collectively, the program represents about 1% of the Eurozone’s GDP and 7% of the total ECB balance sheet.

As a comparison, the U.S. Federal Reserve has committed an amount equivalent to 16% of U.S. GDP through its two quantitative easing programs, QE1 and QE2. In the UK, the Bank of England’s (BoE’s) securities purchases programme represents about 14% of GDP.

One reason the ECB may have been much more resistant to expanding its balance sheet is the lack of a European zero-risk security. In both the United States and Britain the central banks can purchase government securities that represent zero risk to the national central banks. In Europe there is a multitude of government securities that the ECB might purchase but the individual government securities do not represent a European government zero-risk security.

This analysis further points out the need for a euro-bond – a bond that would have the full guarantee of all the European or at least the Eurozone countries. The existence of a euro-bond would allow the ECB to greatly expand its purchase of securities without taking on the questionable individual countries risks. But does the ECB really want to expand its balance sheet? It seems that in December 2011 it decided to finally do so.

Recently the ECB Has Begun Backdoor Quantitative Easing

The European Central Bank (ECB) has chosen to provide relief to the liquidity problems of the European banks, but has chosen to directly distance itself from government sovereign debt problems.

As the following two charts illustrate, the liquidity injections in December were huge, and this has sharply expanded the ECB balance sheet. As Gavyn Davies points out in a December 21 Financial times article, this represents quantitative easing on a significant scale, and “the lines between this form of QE, and the direct monetisation of budget deficits, which is forbidden by the spirit of the eurozone treaties, are becoming increasingly blurred.”

The ECB has stepped up its response to the Eurozone crisis by providing €489bn in unprecedented three-year loans to more than 500 banks across the region.

Under Mario Draghi, its president since November 1, the ECB has resisted political pressure to step up intervention in government bond markets. By flooding the financial system with funds, the ECB hoped to achieve at least three objectives: limit the risk of a major bank collapse; prevent a credit crunch and thereby minimize the coming recession, and, in turn, relieve stress in government debt markets.

Source: Gavyn Davies, Financial Times

As these charts illustrate, up until the month of December 2011, the ECB was much more cautious in terms of balance sheet expansion (i.e. bank reserve expansion) than the central banks in the US and Britain. In other words, the ECB has been very reluctant to play the role of the lender of last resort to the 17 countries in the Eurozone.

Acting as a lender of last resort to 17 countries, which is the traditional role of a central bank, is more delicate and different than dealing with one country in this role. Nonetheless, either a central bank takes on that responsibility, or it is a truncated central bank. Perhaps this caution is a leftover from the influence of the German central bank and its concern with inflation.

In today’s circumstances of impending recession as well as very high unemployment throughout Europe such a concern is unwarranted. There is a clear need for a concerted central bank action to address these problems. The development of a euro-bond would facilitate the central bank’s ability to act in the same manner as have the Federal Reserve in the US and the Bank of England in the United Kingdom.

Closing Comment on Taxes and Revenues

While Europe haggles over some system of regulating the fiscal responsibility of individual member countries it might be time to consider other nations’ revenue systems. One innovative idea that has received little consideration is a Europe-wide Revenue Agency.

There is a great discrepancy in the compliance levels in the countries of Europe. One study points out that in the United Kingdom tax compliance on personal income tax was, in 2002, a high of 80.76 %, while in Italy compliance in the same year was 62.49%.1 One might assume that if compliance levels could be improved at least part of the country deficits would disappear. The model might be the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) that collects taxes for both the federal and provincial governments. In Europe each country would maintain its own tax laws but a central agency across Europe would be charged with the collection of the revenue.

While a European CRA would not be a full answer to the fiscal problems of the separate countries, it would put both governments and their citizens on notice that they share a common concern and a common economic destiny.

Arthur Donner is a Toronto-based economic consultant who has been an advisor to federal and provincial governments. Douglas D. Peters is the former Chief Economist of The Toronto-Dominion Bank and former Secretary of State (Finance) in the federal Liberal government.

1 Christie, Edward and Holzner, Mario, “What Explains Tax Evasion? An Empirical Assessment based on European Data,” The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Working Paper 40, June 2006.