The term “affordable rental housing” is used left and right in Canadian politics. So far in this federal election, housing appears as a central theme, so we are likely to hear the term a lot. But what does affordable housing even mean? And is it truly affordable?

Affordable housing usually refers to rental units built with financial support from governments. In exchange for the support, housing developers have to commit to charge lower rent for a share of new units.

Sounds good, right? But as always, the devil is in the details.

The share of new units designated as affordable in housing developments is usually small, and rarely above 20%. This is why many housing announcements sound fairly unambitious, given the size of the problem, with a lot of political fanfare around a few hundred, sometimes even a few dozen new units. Research shows that Canada is losing affordable rental housing units faster than it is creating them.

The other catch is how long units remain “affordable.” To receive support from governments, developers agree to keep rents for the affordable units below market rates for a set period of time, usually 10 to 20 years, depending on the housing initiative. After that period, landlords can charge whatever they want for units built with government subsidies.

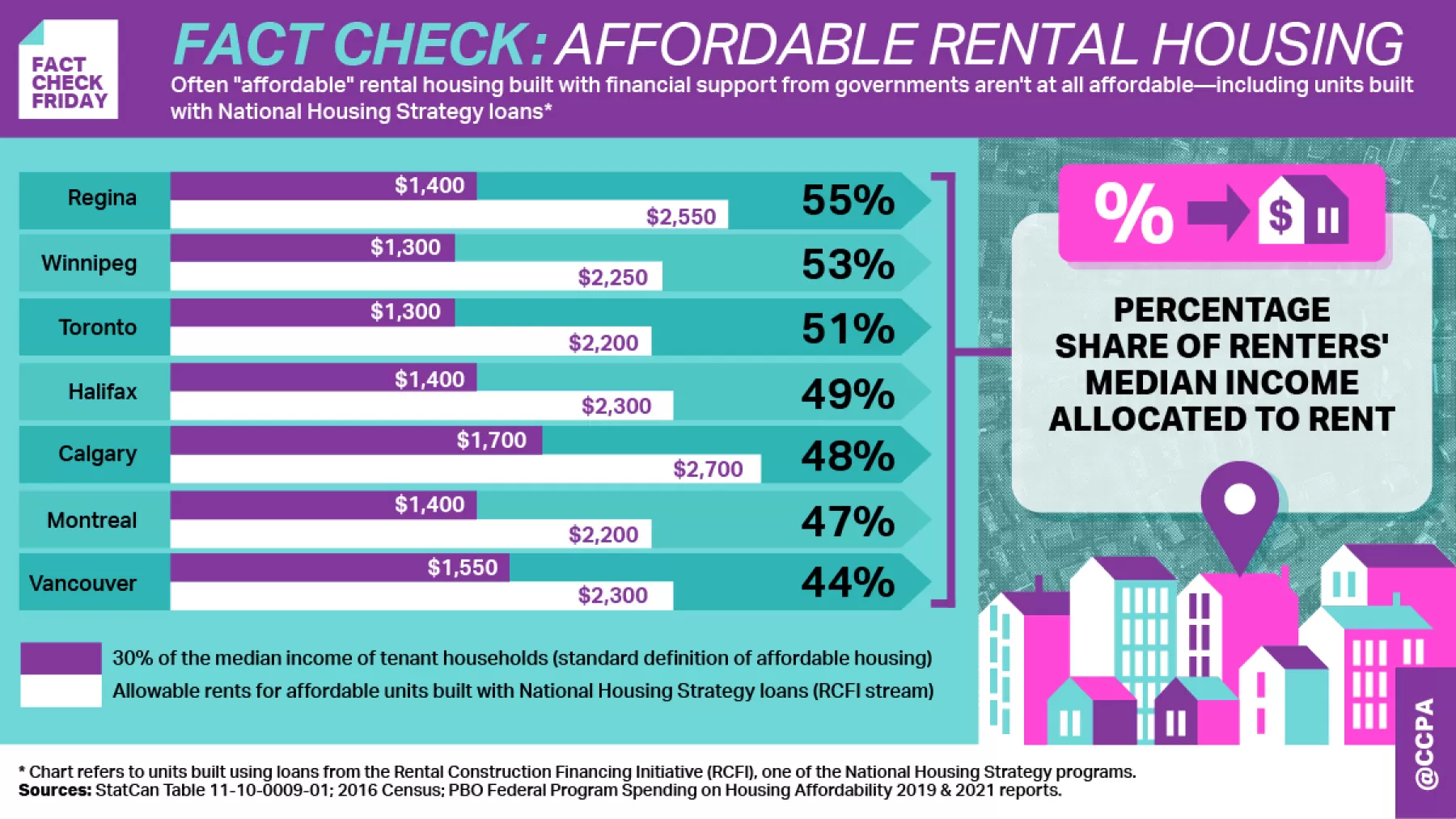

Finally, the affordability thresholds used in agreements with housing developers are, more often than not, awfully inadequate. This frequently results in rent levels that are above what low- and moderate-income tenant households can actually afford.

Here’s an example: Affordable rental units built with the support of loans from the federal National Housing Strategy’s (NHS) Rental Construction Financing Initiative (RCFI) can rent for more than 30% of the median income of tenants—the standard definition of affordable shelter costs. How so? The affordability criteria for these loans has been set at 30% of the median income of all households in a particular area, including all homeowner households whose income are, on average, much higher than that of tenants. As a result, the government is helping finance “affordable rents” that cost between 44% and 55% of tenant households’ incomes in the largest cities in the country. That’s not affordable.

Other housing initiatives use 20% below average-market rent as the affordability threshold.

In cities such as Toronto and Vancouver, that adds up to more than what many tenants can afford to pay. In 2019, for example, this threshold put rents in Toronto $150 above the standard affordability threshold (30% of household income). Some programs use median market rent, instead of average, which improves the criteria slightly. In either case, it’s not affordable.

The other problem with the 20% below average- or median-market rent threshold—and this one applies to most cities—is that rents often rise faster than inflation and wages, so that 20% “discount” can be eaten up in less than a decade. Affordable housing in 2011 may not be in 2021.

Affordability definitions tied to out-of-control rents are fundamentally flawed. Put it this way: if the car ahead of you is driving at 200 kilometres an hour, driving a bit slower than them is not enough to keep you within the speed limit.

For all these reasons, the term “affordable housing” should be challenged whenever presented in vague terms, during this election, and any time after it.

To truly lower rents and make housing affordable for all, we ought to take profit out of the equation by investing in public and non-profit housing.