Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

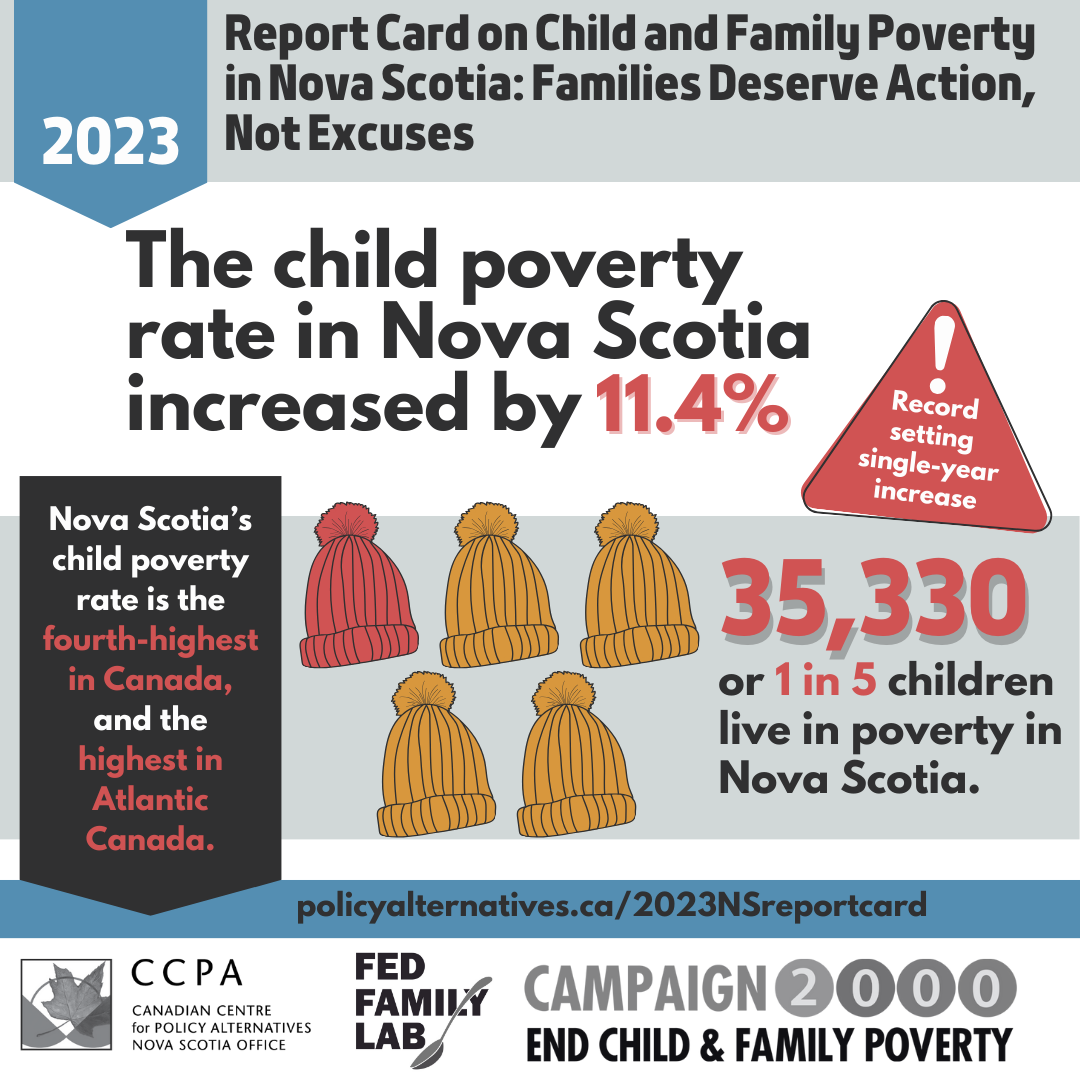

The 2023 Child and Family Poverty Report Card for Nova Scotia finds that poverty increased in Nova Scotia in 2021 from 18.4 per cent to 20.5 per cent. This 11.4 per cent increase is the highest single-year increase since 1989, when the promise was made to eradicate child poverty by the year 2000.

A poverty rate of 20.5 per cent represents 35,330 children living in low-income families, or more than one in five children in Nova Scotia. The rate is one in four for children under the age of two. This report card analyses how the rates differ by geography, social group, family type, and age and lays out a roadmap for ending child and family poverty. Federal and provincial government transfers work to help reduce poverty and in 2021 combined reduced child poverty by 50.5 per cent overall and lifted 36,140 children 0-17 out of poverty.

Given what we know is effective, it is all that more frustrating to hear the response from the current government to the report card’s finding.

In response to media questions about our findings, the Premier of Nova Scotia suggested that the report card does not capture the impact that their “targeted approach” is having on those families. We at the Nova Scotia office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives have been producing the child and family poverty report card for over two decades and can attest to the regularity and nature of excuses. This response can be added to the list of excuses we have heard over the years that typically have been some combination of questioning the evidence.

Their ‘evidence excuses’ have included two main themes: that the report does not use the indicator of low-income or income data source that the government prefers and that the data presented is old.

We will not belabour the measurement tool excuse here, as we present a fulsome account in the report of why we (and our partners across the country) use the Low-Income Measure – After Tax and annual Tax Filer data in reporting the child poverty statistics (along with other measures and data sources) which all show that child poverty increased in NS in 2021.

The data is old excuse generally goes as follows – ‘the report is based on data from two years ago, thus it is unreflective of the current situation, and it doesn’t take into account all we have done since then to address child poverty.’ We have two things to say about this.

First, we always do account for things the government has done that would have reduced poverty since the year the data reflects where we present our recommendations. Given the depth of poverty faced by low-income families, interventions would be ineffective for bringing families’ income above the poverty lines unless they are significant, like the temporary pandemic benefits did in 2020 (from the federal government). The depth of poverty for low-income families using the government’s preferred poverty line, the Market Basket Measure, is almost $13,000 per year for a single parent with one child and almost $18,000 for a couple with two children. Second, based on what we know about families’ current struggles given increased costs – low-income families are very likely experiencing greater hardships now and the poverty rates have likely increased, especially when provincial government transfers are not even indexed to inflation. Keeping everything the same—even if indexed to inflation—would result in no change.

Our reports are always based on the most recent income statistics. There are no more recent income data to show that things are better (or worse) now. All data/statistics have data lags, yet every report card we write confirms our speculations and counters the provincial government’s speculations from two years ago. Sadly, each card dispels the ‘data is old and unreflective of the current situation’ excuse from two years prior.

What we know for certain is that poverty was not eliminated in those two years and thus arguing about how up-to-date the rates only matters if there is a concern that interventions might have eliminated it already.

This year the excuse is that the provincial government’s “targeted” approach is not being captured by the current statistics and that the situation is better than is represented in the report card.

A targeted approach to social programs is a mark of a neoliberal approach to policy design that assumes that poverty is the result of individual pathology and not systemic or structural. This approach is narrowly means-tested with very specific eligibility requirements and bureaucratic quagmires, often requiring divulging of personal information and mountains of paperwork.

Unlike a targeted approach, a universal approach designs programs and services to be accessible to all (a principle incorporated into the social policy framework), and more efficient in delivery and impactful in their outcomes. A targeted approach has dominated for decades and proven ineffectual, yet this government is doubling down on it.

Last year at budget time, Nova Scotia’s minister of finance was asked why there was no increase to income assistance. His response was also that the government was choosing to focus on targeted initiatives instead. What does the government mean by targeted? Are they unaware that income assistance is the hallmark of a targeted approach to social welfare provision?

Income assistance is a means-tested program that considers a household’s financial assets and income. For a single individual without disabilities, deemed employable, that means the maximum amount of income assistance provided is $686 per month and there is no exemption for any earned income for applicants. Why is income assistance not seen as a targeted program? Is it because the government can’t dictate exactly how the money is spent?

Perhaps, by using the word targeted they mean special programs designed to reduce the hardship poverty brings? What many refer to as ‘downstream’ interventions, not preventive ‘upstream’ interventions.

The government announced their targeted and temporary cost-of-living support in December 2022. Most of this money ($8.7 million) flowed to organizations to help soften the blow of poverty and food insecurity. This included $3 million to food banks and other organizations involved in food charity as well as $2.6 million to Family Resource Centres to provide ‘concrete support.’

While no doubt appreciated by these organizations that are bearing the brunt of aiding struggling people and who are no doubt exhausted, they recognize that such approaches to address poverty and food insecurity do nothing to prevent them. The Fed Family Lab recently surveyed family resource staff and heard, reflective of many, that “we see a role for community in supporting one another’s access to affordable healthy food but also feel that government has not taken enough of a role in helping the most vulnerable. Income assistance rates are wholly inadequate. Food insecurity has never been so high, and government keeps sending one off funds to support each crisis but is doing very little to make systemic change.”

The last provincial budget had only three “targeted” expenditures that would directly help these families: heating assistance, rent supplements and a small increase to the NS Child Benefit. Of course, many other expenditures would help many Nova Scotians, but not explicitly or necessarily these families, like reduced child care fees in licensed centres (if you are lucky enough to get access).

As for these three programs. Regarding heating assistance programs, it has narrowed the heating assistance subsidy (HEAT) to once every 24 months and lowered the Heat Assistance Rebate Program (HARP) to $600 instead of the $1000 offered last year. Last year’s budget included a small increase to the NS Child Benefit of $250 a year for the first child. The NS Child Benefit is a very small income transfer that amounts to $127 per month for the first child. It also has a steep clawback/phase-out at a relatively low household income ($32,000). Such a small increase would not be enough to reduce poverty given the depth of poverty faced by individuals on low-income.

Last year’s budget also had an increase to the number of rent supplements available by 1,000, for a total of 8,000 rent supplements. These rent supplements undoubtedly help some households, but not very many given how many are currently living in poverty or those struggling with housing insecurity. The government even narrowed who gets access to these supplements from those paying 30% of their income on rent (a measure of affordability) to those who are paying 50% of their income on rent. They admit that the supply is very limited and they are unable to meet the demand. The government has also capped the subsidy amount at the difference between average market rent and tenant’s portion of 30 per cent of their income.

The average market rent amount does not capture true housing costs especially given the loopholes in the rent cap that sees turnover units with much higher rental increases. It is also concerning that these supplements are likely temporary with the end of the federal bi-lateral in 2028. It is equally concerning that the rent cap has increased to five per cent and is set to be removed at the end of December 2025.

All of this targeted spending did not amount to very much in a $14 billion budget, especially considering the government described a half-a-billion investment in building bridges and highways as the most significant expense in last year’s budget that would go towards “building healthy communities.” A half-a billion investment in the social safety net, expanding universal public services and income supports, would go a long way to help Nova Scotians to be healthy. Addressing the social determinants of health is key to healthy people and communities.

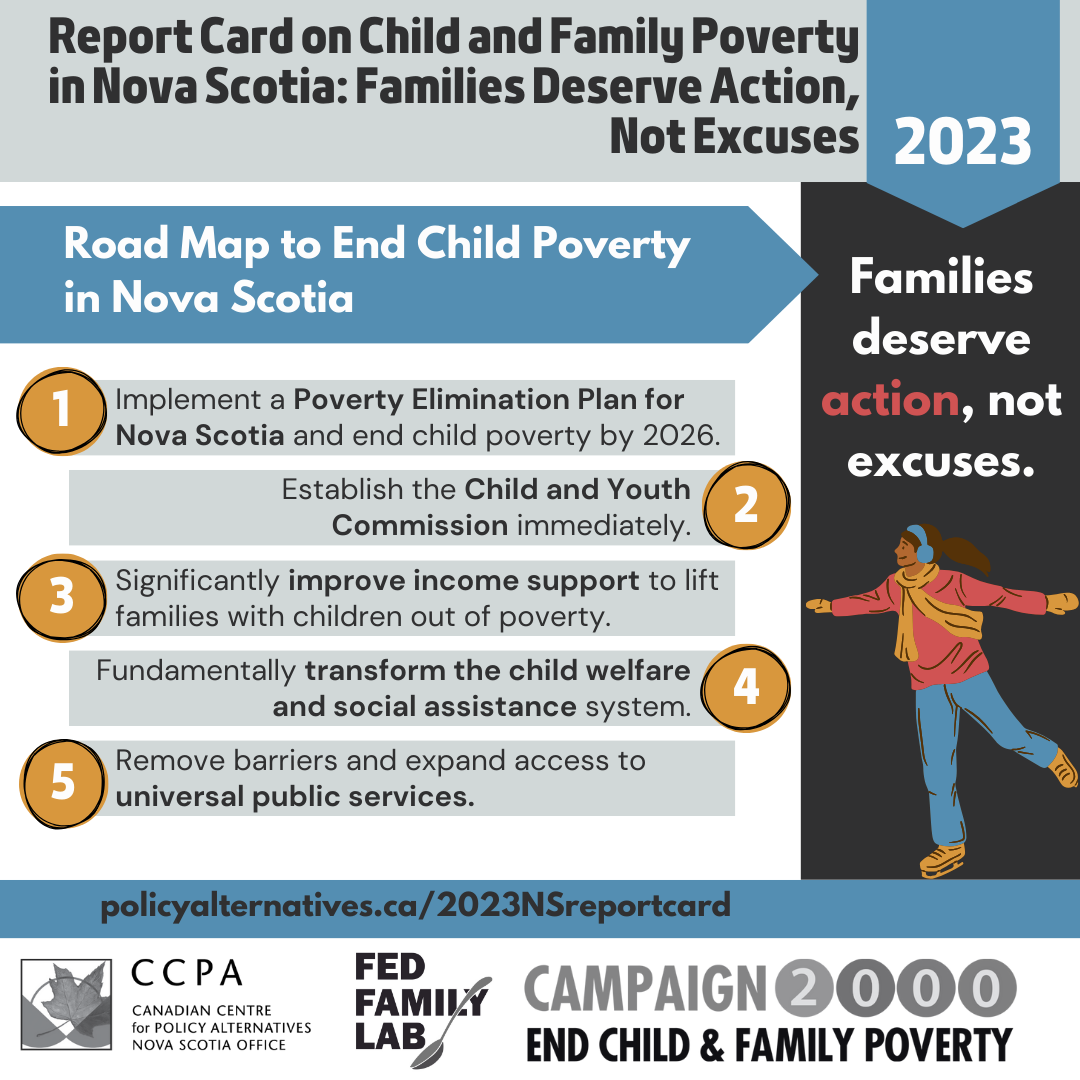

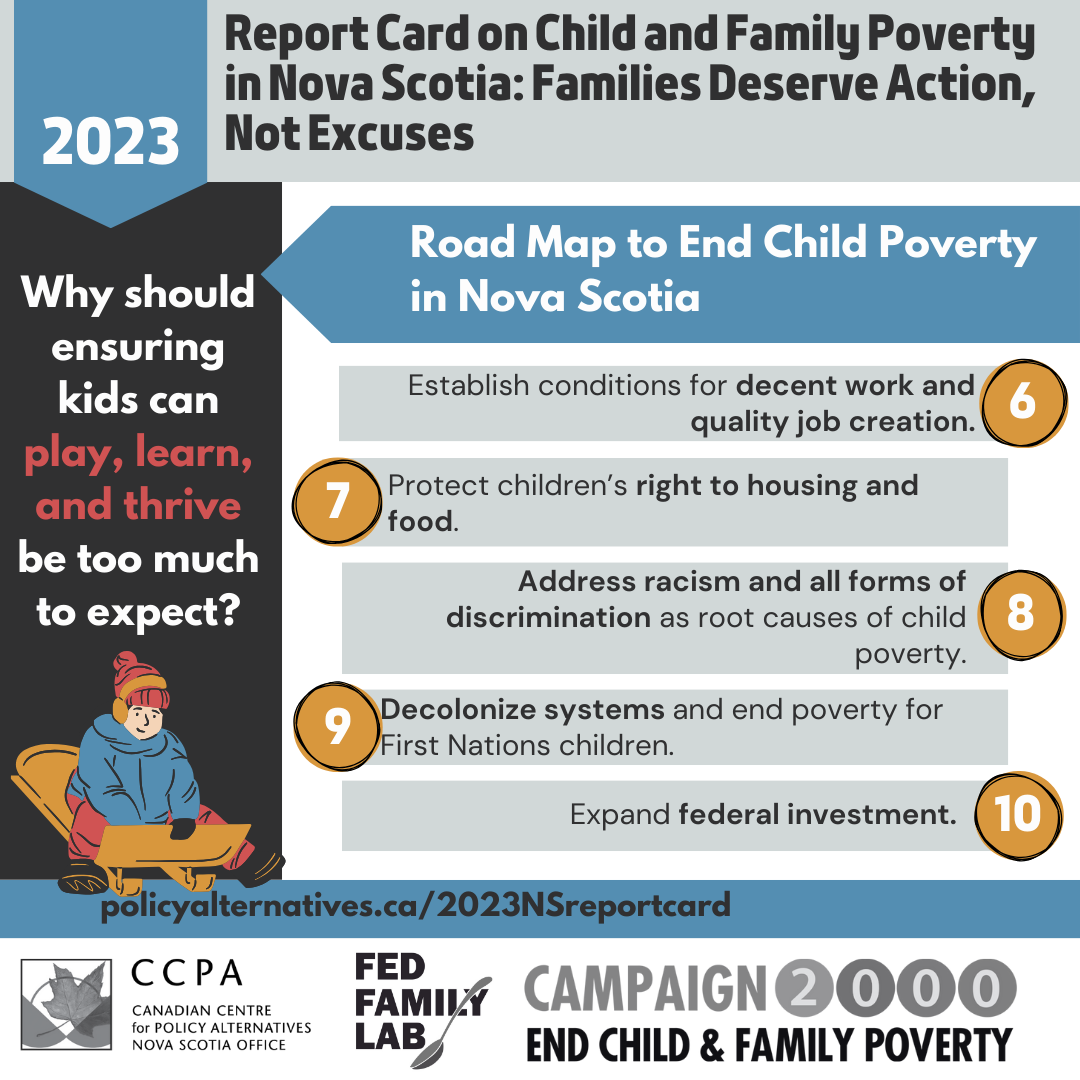

No more excuses. Our report card outlines a roadmap and specific recommendations that should be implemented. Time for the Nova Scotia government to pick a timeline and a target for poverty elimination. Nova Scotia has the fiscal capacity to build that poverty-free future where kids can be kids, housed, fed, and thriving. Families are counting on you.