Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Canada is marking Gender Equality Week for the first time this week—another sign that closing the gender gap is on the federal agenda. And yet while we have been making measured progress, women are still waiting for meaningful change. Years of effort to remove entrenched economic, cultural and social barriers to women’s progress are not landing the results we all expected by now.

The Trudeau government has developed tools and accountability measures to promote gender equality and mainstream it across policy and programs. It has increased funding for community organizations, skills training and apprenticeships, parental leave and violence programming. Internationally, the government is actively promoting the rights of women and girls and making important investments in education and poverty reduction.

At the same time, there is mounting evidence of a backlash against women’s rights. Ongoing efforts to close the gaps in areas like employment or the availability of public services such as child care are called a distraction from, or a threat to, meaningful action on other allegedly more important public policy challenges.

In fact, the evidence shows that Canada has made only modest progress closing its gender gap this past decade, and effectively stalled on key economic indicators and legislative representation. It’s a sobering thought that the best we’ve done is gender parity in the federal cabinet.

So are we done yet? Have we closed the gap? Not by a long shot.

Reality check: How does Canada measure up?* The World Economic Forum reports annually on the progress of countries in closing the gap between men and women in four areas: education, health, the economy and politics. Their Global Gender Gap Index focuses on the gap between men and women, rather than overall levels of well-being. It does so in order to measure the difference between the access women and men have to available public goods, and not the overall wealth of their respective countries. Countries with the smallest gaps—where outcomes for women are closer to those for men—are ranked more highly than those with larger gaps.

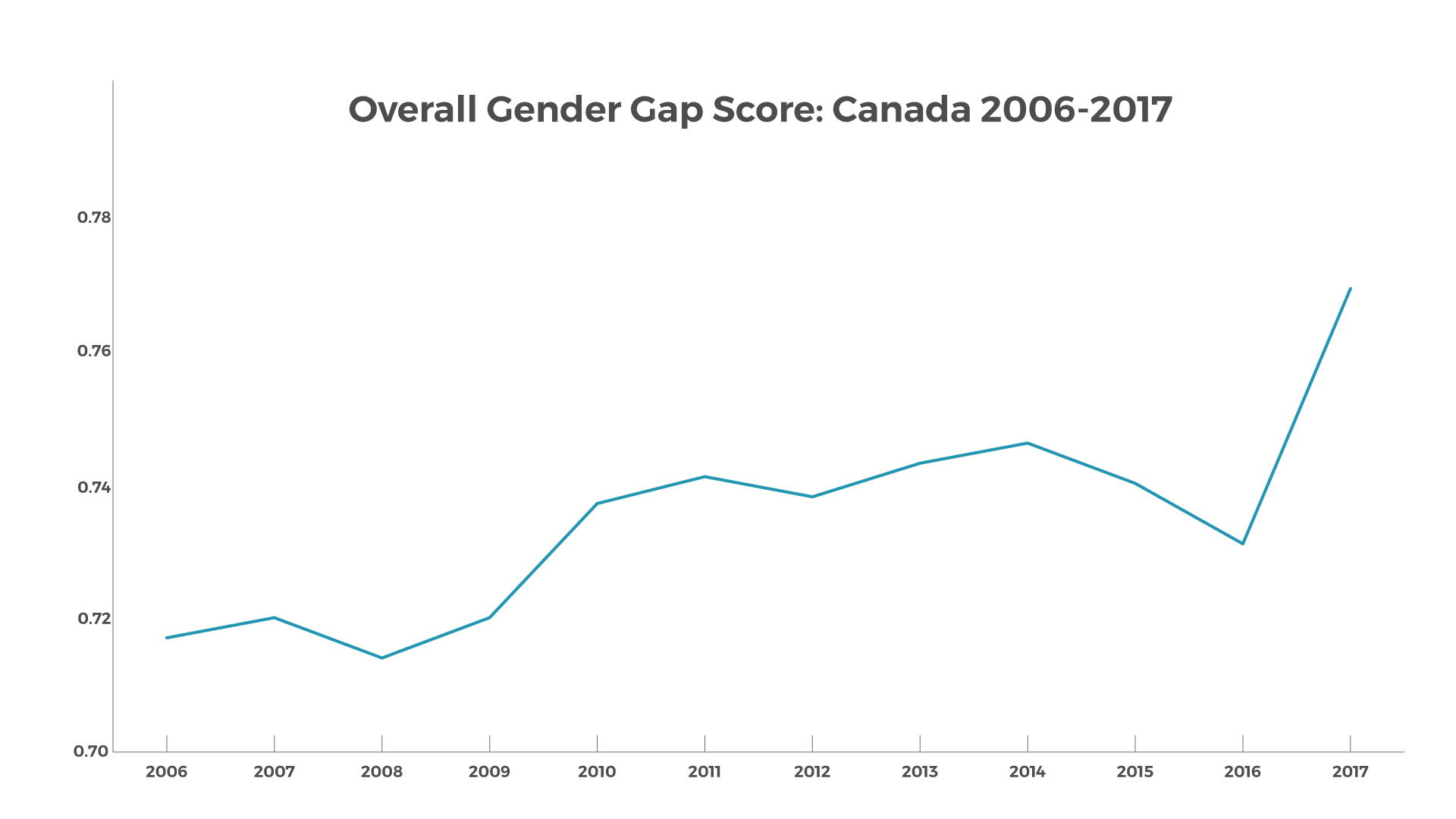

Looking back to 2006, Canada has placed among the top 25% of countries each year, consistently scoring around 0.73 out of 1.00 (with 1.00 representing no gap between men and women), with an average ranking of 22 out of the roughly 130+ countries captured in the Index.

It is Canada’s rate of change over the past decade that demands attention. Canada eked out only meagre increases in its gender gap score between 2006 and 2016, averaging 0.15 percentage points a year. By 2015, our ranking had fallen from 19th to 30th place and then, in 2016, to 35th place.

Source: All of the data presented in this report (unless otherwise noted) are taken from the World Economic Forum, The Global Gender Gap Report, editions 2006 through 2017.

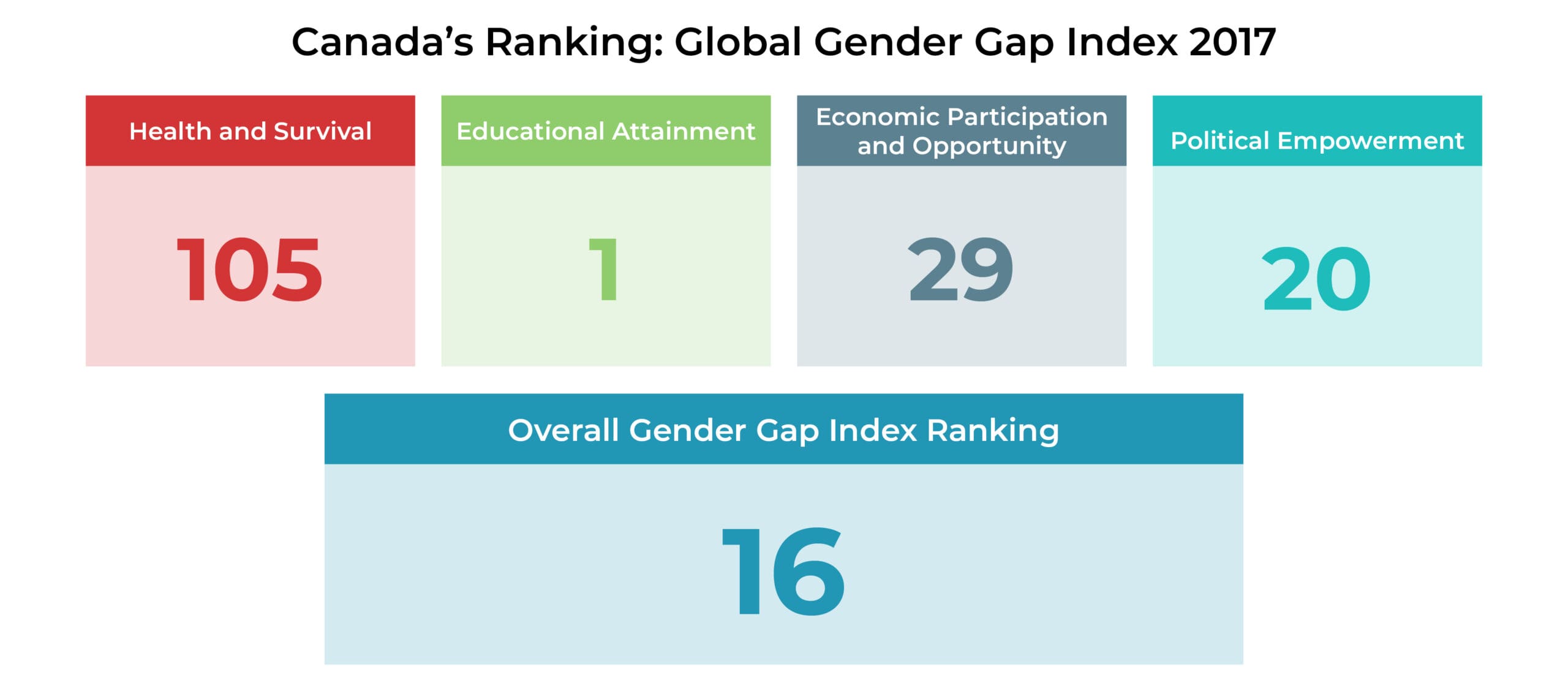

As shown in the graph here, 2017 marked a turnaround. Canada’s score jumped by 0.038 (from 0.731 to 0.769), and it moved up the Index to 16th out of 144 countries, the direct result of a boost in women’s representation in the federal cabinet after the 2015 election. The increase in the proportion of women in ministerial positions was the highlight of the decade.

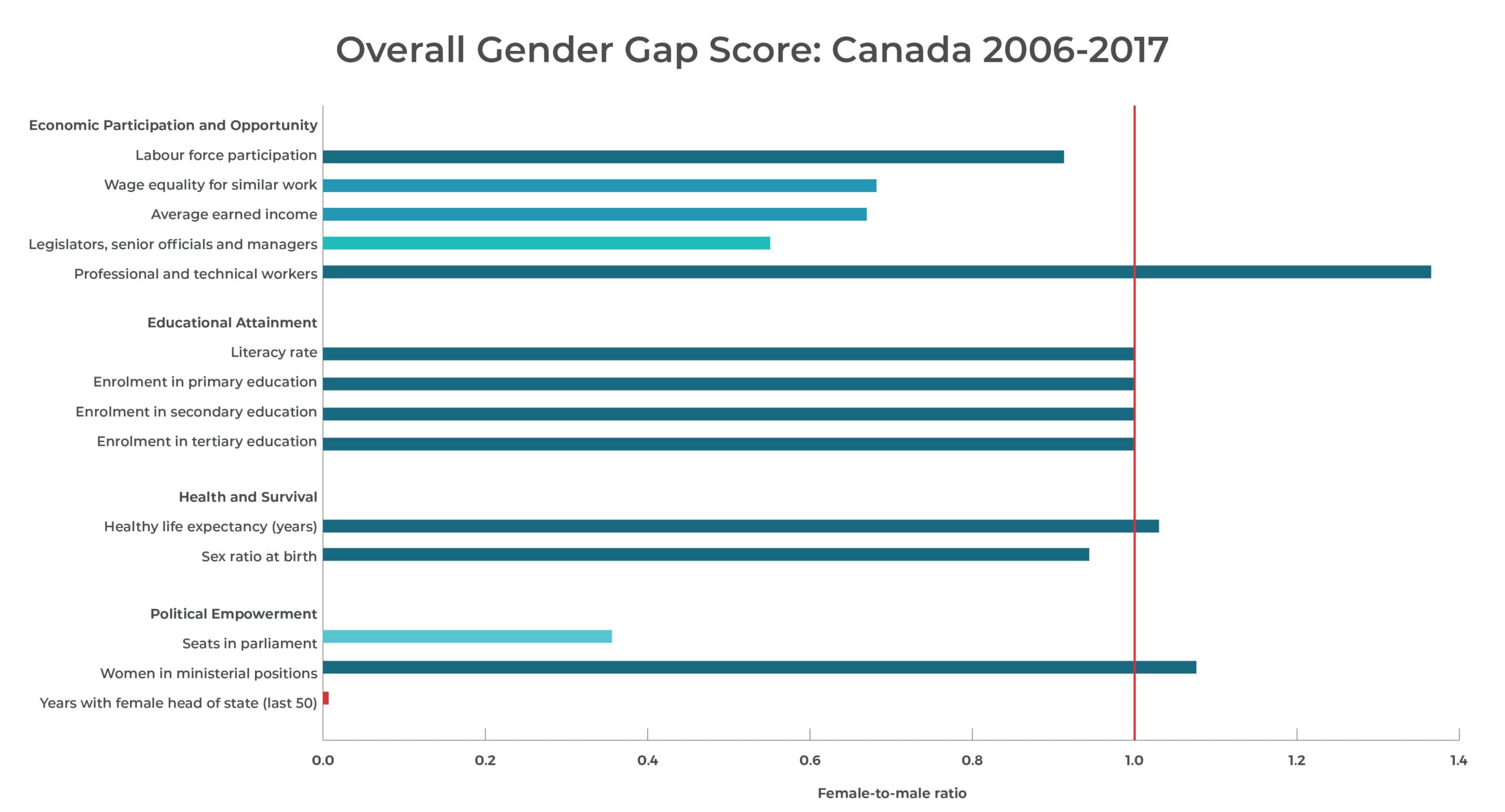

A closer examination reveals uneven levels of progress across the different areas. The good news: Canada has had a nearly perfect score in the areas of health and survival and educational attainment over the past 12 years. The health score is based on healthy life expectancy and sex ratios at birth. The education score is based on literacy and school enrolment at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels. In these two categories Canada has averaged 0.98 and 1.00, respectively, between 2006 and 2017.

Canada’s comparatively low ranking on health and survival (105/144) is related to healthy life expectancy. Canadian women have longer healthy life expectancies than men (73.3 vs. 71.3 years), but in some countries such as Japan, the gap in women’s favour is larger.

Wide gaps in wages and political representation Gender parity in health and education, however, has not translated into notable progress with respect to economic and political empowerment. Canada’s score for economic participation and opportunity is well below our positive standing in health and education. Between 2006 and 2017, Canada’s gender gap in this area inched forward an average of 0.1% per year. That is one-tenth of one percentage point. At this rate, it will take 196 years to close the economic gender gap in Canada.

Economic participation and opportunity is calculated based on labour force participation, earned income, wage equality, and the ratio of women to men in professional, technical and management positions. Canada’s economic ranking in 2017 was 29th place, down from its 10th place position in 2006.

The gap between men’s and women’s earnings is a significant factor in Canada’s mediocre showing in this area. Although employment incomes for men and women overall have grown since 2006, the gap between men’s and women’s share of income has been nearly stagnant—rising from 0.64 in 2006 to 0.67 in 2017—even as education levels among women have surpassed those of men.

Canada’s gender pay gap is one of the highest in the OECD, ranking 30th out of 36 countries, behind all European countries and the United States. Average earnings among Canadian women are certainly higher than in many OECD countries, but full-time female employees still only earn 81 cents for every dollar that full-time male employees earn.

Overall, women’s estimated earned income in Canada is roughly two-thirds that of men (0.67), well behind leaders such as Norway (0.79) and Sweden (0.78). The Federal Pay Equity Network estimates that over a 45-year career, the average woman will effectively work 14 years without pay as a result of the gender pay gap.

However, the biggest drag on Canada’s Gender Gap score in this area is its poor performance with respect to the share of women who make up our country’s legislators, senior officials and managers. The ratio of women to men in these roles has remained nearly unchanged since 2006 at 0.56, while our ranking has fallen from 18th to 44th place as other countries have improved their standing. In 2017, men outnumbered women in these professions by two to one.

What emerges from these indicators is this: the closer women get to the top, the greater the barriers to achieving equality. This trend is startlingly clear in the measures of political participation. Canada’s gender gap score in political empowerment was a very low 0.159 in 2006. With an average annual rate of progress of 0.6%, Canada had edged up to 0.222 by 2016, ranking 49th out of 144 countries.

In 2017, Canada’s score jumped from 0.222 to 0.361, an increase of almost 40%. As mentioned above, this increase was almost entirely due to the appointment of an equal number of male and female federal cabinet ministers in 2015. On this indicator, Canada now ranks first in the world.

The number of women serving in Parliament, however, has certainly not improved at the same rate; in 2017, just one-quarter (26%) of all MPs were women. Political participation is the one area measured by the global gender gap in which rapid change is possible (all it takes is an election). Yet there is a considerable distance to go to closing the gap.

No time for complacency These numbers should be a reality check. Women in Canada still make roughly two-thirds of what men make and continue to shoulder a disproportionate share of work in the home—to say nothing of the much higher barriers that groups such as racialized women and women with disabilities face.

But we can’t be complacent. Around the world, conservative forces are rolling back women’s rights and silencing women’s voices. This distain is all too familiar to women’s organizations and allies fighting for better child care, stronger labour standards for precarious workers, and reproductive rights.

Progress is never inevitable, nor will one week a year bring the profile needed to close Canada’s gender gaps. That will take more concerted efforts of the kind put forward in the Alternative Federal Budget. For example, the 2019 AFB makes the following recommendations for putting gender equality at the heart of economic policy:

- Investing in the sectors where women work today and ensuring that job stimulus and infrastructure spending is directed at Canada’s entire labour force. The IMF estimates that narrowing the gender gap by putting more women to work would boost real GDP by 4%.

- Providing tailored supports and training for women who face employment barriers or work part-time involuntarily, and recognizing the qualifications of women who have been out of the workforce caring for children and family members. These measures would increase both the number of women working full time and household incomes

- Investing in universal child care and introducing a paid paternity leave, building on the success of the Quebec model. Public child care would provide critical support for parents and help shift the balance of unpaid work.

- Investing in a fully resourced National Action Plan to address Violence against Women, based on the Blueprint for a National Action Plan, and bringing federal per capita spending on the issue in line with provincial spending.

For further information about the gender gap in Canada, stay tuned for the next edition of The Best and Worst Places to be a Woman in Canada in 2019. This report looks that the gender gap across large cities highlighting the great work being done at the community level to advance gender equality.

*This Brief provides an update of an article written by Kate MacInturff in 2013. See: Closing Canada’s Gender Gap: Year 2240 Here We Come! Behind the Numbers, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Katherine Scott is a senior economist with the CCPA’s National Office, working on gender equality and public policy research. You can find her on twitter at @ScottKatherineJ.