Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

This week, Behind the Numbers is publishing a series examining Canada’s economic recovery and scrutinizing the government’s economic message. Monday, we looked at GDP and Economic Growth, yesterday we looked at unemployment in Canada; today and Thursday we will be looking at indicators of employment quality in the economy.

“We will take decisive action to ensure our economy will create good jobs and sustain a higher quality of life for our children and grandchildren.”– 2012 Budget speech

As we saw yesterday, the recovery of Canada’s job market since the recession has been mid-ranged compared to rest of the developed world; a natural follow-up question to this is “what is the quality of these jobs?”

A commonly accepted definition of a “good job” is one that is full-time and that is a permanent, long-term position. Using this definition, we can examine the quality of jobs during the recovery.

Underemployment – Not Working to our Potential

Perhaps the clearest indicator of poor-quality employment in the labour market is the proportion of people who work part-time but would prefer to be working full-time. This measure is called the involuntary part-time rate and is a better indicator of employment quality than a simple full-time versus part-time employment ratio because it controls for people who are working part-time by choice. Voluntary part-time workers have chosen their status (because of family obligations, school, or a variety of other reasons) but that is not the case with involuntarily part-time employment – those workers simply cannot find the full time jobs they want.

In short, involuntary part-time workers are underemployed and not working as much as they would like.

For this analysis, involuntary part-time employment is calculated as a proportion of total employment. For example, if a hypothetical economy had 10 million employed individuals and 1 million of them were employed as involuntary part-time workers, then the involuntary part-time employment rate would be 10%.

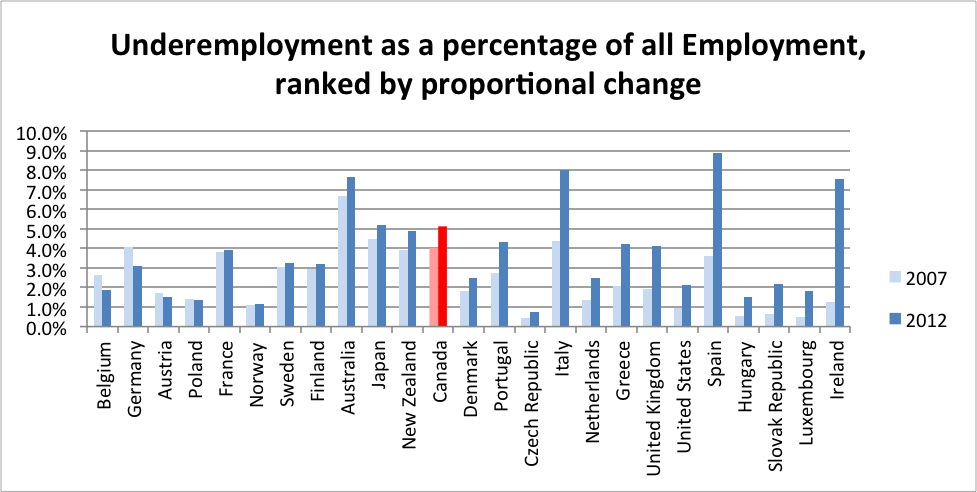

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics, Share of involuntary part-timers in total employment. Note: Complete data only available for 25 countries. Data is only available annually.

Canada had an involuntary part-time employment rate of 5.1% in 2012. In terms of current values, this is one of the highest of the OECD countries with data on involuntary part-time employment. Ranked from best to worst, Canada’s current rate of involuntary part-time employment would put it at 20th of 25 OECD countries with comparable data.

Canada’s relatively high proportion of involuntary part-time employment partially predates the recession, and it has gotten worse over the recession and recovery.

Notably, Canada’s rate of involuntary part-time employment increased 1.1 points from pre-recession (2007) to 2012. Proportionally, this rate increase, from 4.0 to 5.1, is a change of 27% over the pre-recession levels. This rate of increase is at the mid-point of the OECD experiences during recovery, specifically, 12th out 25 in terms of proportional change and this OECD ranking earns Canada’s recovery a grade of C.

Based on December 2012 labour force statistics, an increase of 1.1 percentage points means that there are approximately 195,000 more people in involuntary part-time positions now than at the prerecession rate.

Good jobs, eh?

Be sure to join us tomorrow as we discuss another aspect of employment quality over the recession: precariousness.

To learn more about the methodology behind this blog series, click here.

Kayle Hatt is the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ 2013 Andrew Jackson Progressive Economics Intern.