Ontario announced plans in May to boost the minimum wage to $15 an hour by January 2019. In my recent report, Ontario Needs a Raise, I calculated who would benefit most from this overdue wage hike, but Indigenous workers were not included because the Labour Force Survey (LFS) public use microdata file (PUMF) I was using did not specify Indigenous identity. Now that this data is available, let’s look at those numbers too.

Stats record show there were 116,000 Indigenous workers in Ontario in the first six months of 2017, and the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) showed the province is home to more working-age Indigenous adults than any other in Canada (2016 census figures aren’t out yet). Due to gaps in the LFS, we don’t have figures for on-reserve workers, which represent roughly a quarter of all Indigenous workers in Ontario, almost all of whom are First Nations.

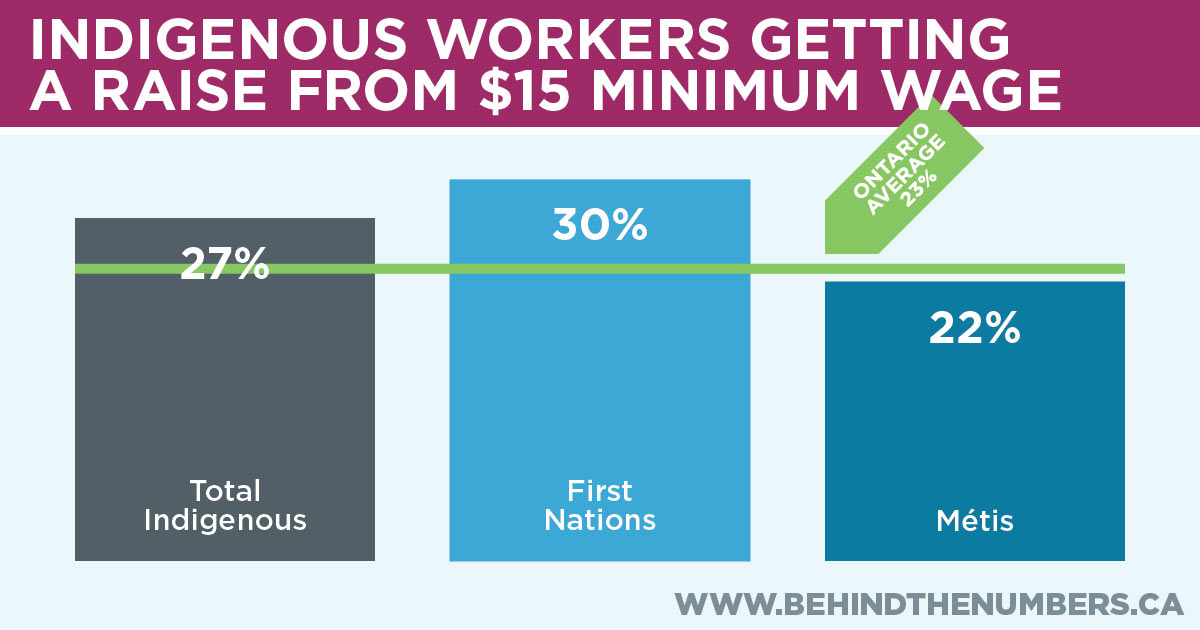

The LFS also excludes self-employed workers.In general, 27% of Indigenous workers in Ontario will see a raise when the minimum wage hits $15 an hour. This is heavily weighted to First Nations workers, 30% of whom will see a bump to their income; 22% of Métis workers will see their wages rise, which is close to the overall Ontario average (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) of 23%.

Source: Labour Force Survey, custom tabulation (January to June 2017) and author’s calculations.

One of the interesting features of the Indigenous workforce is that there are more women than men working, a trend that is relatively stronger for First Nations in Ontario. This is the opposite of what you find in the general population, where slightly more men than women are working.

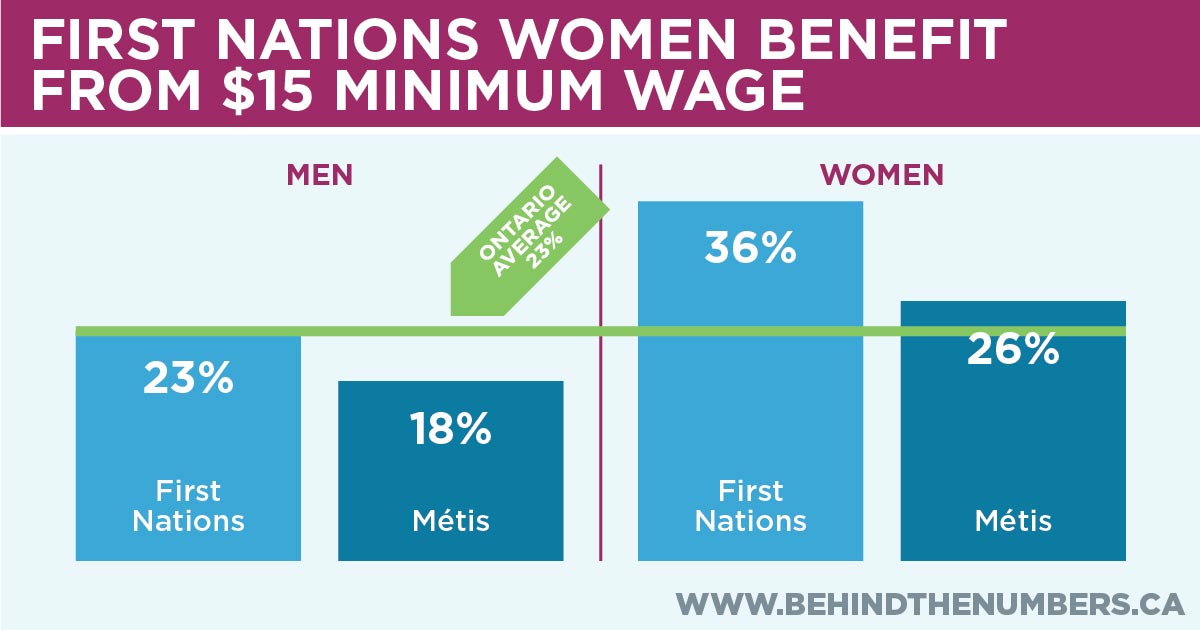

If we break down the figures above by gender, we can see that the minimum wage hike will produce a particularly large benefit for First Nations women in the workforce, 36% of whom will get a raise on January 1, 2019, which explains the bigger benefit to First Nations families (given the high participation rate of women in the workforce).

The effect is similar to the strong impact a $15 minimum wage will have on the incomes of immigrant women, 42% of whom will get a raise. Meanwhile, 26% of Métis women will benefit from the hike, which is similar to the 27% of Ontario women in general who would get a raise at $15 per hour.

Source: Labour Force Survey, custom tabulation (January to June 2017) and authors calculations.

A greater portion of First Nations men (23%) benefit from the minimum wage boost than men in general in Ontario (19%). As with Métis women, Métis men see about the same benefit as the overall male population in the province, which is likely due to Métis people often living in more urban environments with better access to the job market.

It’s unfortunate that I have to mention this, but all of these Indigenous workers presently pay income tax as well as making Canada Pension Plan and employment insurance contributions, just like everyone else in Ontario. When Indigenous Ontarians see a raise, they make even higher payments to these programs, to everyone’s benefit.

The most important takeaway here is that raising the minimum wage will improve the livelihoods of Indigenous workers and their families, and will benefit other historically economically disenfranchised groups as well. This labour market measure will help buffer First Nations families from otherwise appalling levels of poverty, particularly child poverty.

This blog is part of a series that examines who will benefit from a proposed move to $15 an hour minimum wage in Ontario. For a look at why the raise is good for Ontario workers, read CCPA Ontario director Trish Hennessy’s take here. Calculations on who would benefit from a raise in Toronto and Hamilton are also available.

David Macdonald is a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter @DavicMacCnd.