Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

One hundred years ago—July 1, 1923—the Canadian government passed “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration.” Known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was an overtly racist law prohibiting the arrival of newcomers from China. It also required all people of Chinese heritage, including the Canadian-born, to register with the federal government in order to stay in the country. Chinese Canadian communities across the country mobilized to lobby against the act but in the end their efforts failed to stop its passage. Thus, July 1 came to be known as “Humiliation Day” for many Chinese Canadians.

On the 100-year anniversary of the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The Monitor is releasing a series analysing the context in which the Act passed, resistance to the law, and its historical legacy. These articles are a serialization of the booklet 1923: Challenging Racism Past & Present, which you can read in full at https://challengingracism.ca/

Read the full series

This article is one piece of a larger series, which looks at the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act, 100 years after it passed in 1923.

We will update this list with hyperlinks as the series is released.

Chapter 1: Challenging Racism, 1912-1914

Chapter 2: Anti-Racism and the War, 1914 – 1916

Chapter 3: The Revolts, 1917-1919

Chapter 4: Global Challenges to Racism, 1919-1922

Chapter 5: Backlash, 1920-1922You are here: Chapter 6: The Chinese Exclusion Act and More, 1923

Afterword: Echoes of 1923?

1923 was a year of major setbacks for anti-racist and anti-colonial struggle in Canada, as two years of racist backlash in BC converged with harsher federal policies towards Indigenous and Asian people. Canada’s parliament passed Bill 45, An Act respecting Chinese Immigration, excluding Chinese people from immigrating to Canada and introducing new modes of surveillance on Chinese Canadians. Japanese Canadians were also targeted and the government moved to suppress the sovereignty of The Six Nations of Grand River.

The Chinese Exclusion Act

Parliament had already set the scene for the Chinese Exclusion Act when in 1922 it passed a resolution calling for the restriction of Asian immigration. Chinese communities across Canada took actions to dissuade the government from such a path. Unfortunately, their allies were few.

Initially, the Liberal government explored the possibility of negotiating a quota system with the Chinese government, similar to Canada’s agreement with the Japanese government that restricted the number of newcomers per year. However, Immigration Department officials objected. Instead, they promoted complete Chinese exclusion, using legislation as the means to do so. Having focused their attack on Chinese Canadians, the government also took measures to further reduce immigration from Japan.

Parliament began discussing Bill 45 in the spring session of 1923. At the time, a few missionaries argued against the legislation, but for the most part Chinese Canadians waged a brave but lonely struggle for justice. Arrayed against them were almost all members of parliament, the national Retail Merchants Association, the Trades and Labour Congress, and many others.

Much of the discussion in parliament focused on assuring that merchants and students would also be excluded. Though a few minor details of the bill were changed as it passed through the parliamentary process, overall, the legislation remained drastic.

Local and diplomatic efforts to stop the Chinese Exclusion Act failed. An editorial published in the Chinese Times attributed the failure to defeat the bill to internal divisions among the Chinese in Canada and political weakness and disunity in China.

In the end, not only was Chinese immigration halted but the legislation also imposed new restrictions on all Chinese Canadians, including strict measures of surveillance.

The Contested Path to Exclusion in Parliament, 1923

March 2 Charles Stewart (Acting Minister of Immigration and Colonization) introduces Bill 45, An Act respecting Chinese Immigration.

April 29 Close to 2,000 people from Chinese communities across the country gather in Toronto to protest the proposed act.

April 30 Stewart moves the second reading of Bill 45. The House Commons discusses the bill in detail.

May 4 Bill 45 is read a third time and passed.

May 7 A delegation from the Chinese Association of Canada arrives in Ottawa to deliver a petition against the bill and lobby senators.

May 8 Bill 45 is introduced in the Senate for approval. A special Senate committee is later struck to discuss the bill.

May 17 Sun Yat-Sen, head of the southern government in China, writes to the Canadian government to demand suspension of Bill 45. His request is dismissed.

June 26 The Senate adopts amendments regarding undocumented workers and non-English speakers, and passes the bill.

June 30 Following the House of Commons’ approval of the Senate’s amendments, the Governor General gives Royal Assent to An Act respecting Chinese Immigration.

From the Parliamentary Discussions

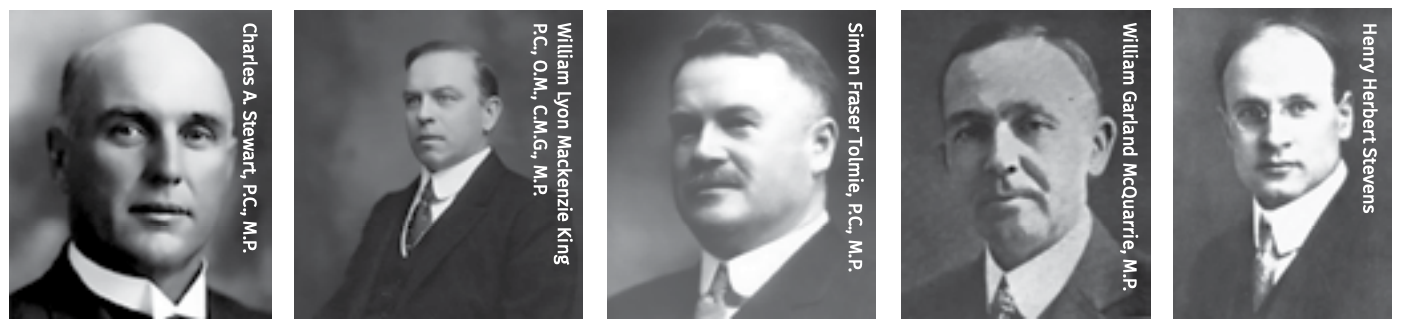

Mackenzie King (Prime Minister) “For years past it has been recognized that it is not in the interests of Canada to admit to this country large numbers of persons from the Orient.”

Simon Fraser Tolmie (Victoria MP, future premier of BC): “British Columbians as a whole are anxious to maintain international relations and also to maintain our high standards as a Christian community; but we do not want to do that at the expense of giving up our country to the Asiatics.”

W. G. McQuarrie (MP for New Westminster): “I have every respect for the industry of the Chinaman, and as far as it goes in their own country, the Chinese are a very estimable people. The great difficulty is that in this country they cannot be assimilated and therefore they always exist as a foreign element in our midst.”

A. W. Neill (MP for Alberni-Comox): “I will say that the only fault I have to find is that the minister did not insert the words “Asiatic origin” which would make it apply to the Japanese.”

Some of the many white MPs who worked to get the Chinese Exclusion Act passed.

The final version, given Royal Assent on June 30, 1923, was draconian and became known at the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Act went into effect on July 1, 1923, Dominion Day (now known as Canada Day). Chinese people living in Canada had until June 30, 1924, to register with the immigration office.

The Act required that “every person of Chinese origin or descent in Canada, irrespective of allegiance or citizenship, shall register with such officer or officers and at such place or places as are designated by the Governor General in Council for that purpose, and obtain a certificate in the form prescribed.” Failure to register by the deadline could result in fines, arrest, or deportation. In the years following, July 1 was observed as Humiliation Day by many Chinese Canadians.

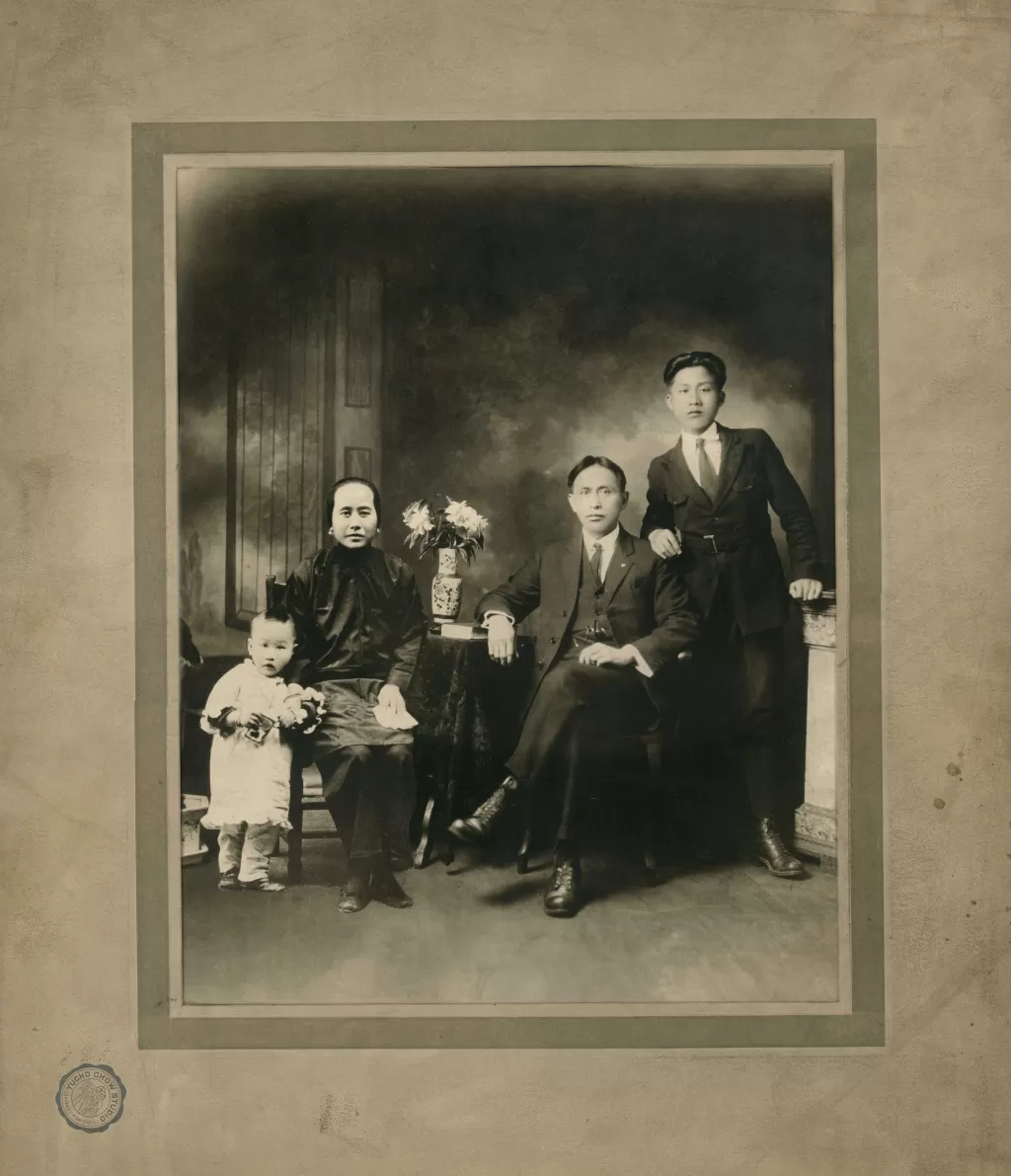

One of the immediate outcomes of the exclusionary measures was a complete stop in the growth of Chinese Canadian communities in Canada. In the 24 years during which the Exclusion Act was in effect, some Chinese men returned to China, while the lack of Chinese women and new immigrants drastically slowed down the growth of Chinese communities. It became more common for Chinese men to intermarry with women outside of the Chinese community.

Not only did families struggle to grow, but they also coped with devastating separation. Most of the Chinese living in Canada had arrived alone to seek work opportunities overseas. The exorbitant cost of the head tax prevented most people from bringing their wives and children to Canada. While some men were able to save money to return to China to visit their families, others remained in Canada and were separated from their family in China for decades, leading to the creation of diasporic ‘bachelor societies.’

The Chinese Exclusion Act remained in place until after 1947 but the hardships that it created persisted far longer. Even after the war, Chinese immigration policy limited immigration to a quota of a few hundred per year and employed a restrictive family reunification program.

Exclusion Plus

The Chinese Exclusion Act was not the only regressive measure in 1923. Other measures were taken against Asian Canadians while federal and provincial governments cracked down on First Nations, including:

Japanese Immigration Further Reduced

Under pressure to expand the Chinese Exclusion Act to include a ban on all Asian immigration, prime minister Mackenzie King opted to negotiate separately with the Japanese government. King explained that the Japanese government could be pressed to make the reductions itself in order to avoid “invidious legislation.”

The Japanese government reluctantly agreed to reduce annual emigration to Canada from the previous quota of 400 per year to 150 on August 23, 1923. In 1928, spouses were no longer permitted to join their husbands in Canada.

BC Government Ratifies McKenna-McBride Act

On July 26, 1923, the BC government ratified the McKenna-McBride report, as did the federal government the following year. In response, the Allied Tribes of BC went directly to the Canadian parliament, submitting a petition demanding a special parliamentary committee to consider their title claim. The parliamentary enquiry took place, but in 1926 it repudiated the Allied Tribes’ claims.

In order to quash any further legal appeals by First Nations, the federal government subsequently introduced Section 41 of the Indian Act, which made it illegal for Indigenous Nations to pursue legal actions regarding land claims. Indigenous resistance continued in various forms, but the Allied Tribes would disappear, as had the League of Indians.

Japanese Canadian Fishers Restricted

In 1922, the federal government created the BC Fisheries Commission, that included MPs W.G. McQuarrie (New Westminster) and A.W. Neil (Alberni-Comox). Based on the BC Fisheries Commission report, the Department of Fisheries issued 800 fewer gillnet licenses to Japanese Canadian fishers in 1923 than in 1922. Nor were they assigned any licenses for salmon purse seine or drag- seine fishing boats. Licenses were further reduced in the following years.

DIA Attacks Six Nations Confederacy

In the spring of 1923, the government stationed a permanent RCMP detachment on Six Nations territory (Ohsweken) and selected a white lawyer to conduct an “inquiry” into Six Nations affairs, provoking the Confederacy Council to seek recognition of their sovereignty abroad.

Meanwhile, the DIA inquiry recommended replacing the Confederacy’s hereditary leadership with an elected band council. The following year, the DIA forcibly dismissed the Confederacy’s traditional council and imposed a band council. A small group of 56 Six Nations’ members voted in elections for the band council and 800 members signed a resolution condemning the government’s actions.

The effects of 1923 were felt by racialized groups across the board. Stricter enforcement of immigration regulations from 1919 targeted eastern Europeans and officials were “detaining and deporting Jews for the slightest of reasons.” This period saw a rise in antisemitism, particularly in Ontario and Quebec, where anti-Jewish property covenants proliferated, media stereotypes regarding Jews increased, and universities introduced quotas for Jews.

The communities involved were, for the most part, each fighting their battles in separate corners and often faced internal divisions as well. In this light, it was not possible to achieve victories against the racist backlash and assaults of 1920-1923.

That does not mean that Indigenous, Black, and other racialized peoples in Canada did not continue to resist white supremacy. They organized carefully, avoiding for the most part direct confrontations with the government or the RCMP. The ensuing years were difficult as community populations in several cases reached new lows. At the same time, new generations were born and would soon take active roles in challenging racism and white supremacy.

Deskaheh: “I Am Going to Geneva”

In 1923, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (also known as the Six Nations or the Iroquois Confederacy) dispatched their spokesperson, Deskaheh, hereditary chief of the Cayuga nation, to Geneva to lobby the League of Nations to recognize the Six Nations as an independent nation under Article 17 of the League’s covenant.

Deskaheh first crossed into the United States and then traveled to Europe carrying travel papers issued by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Accompanied by George Decker, a lawyer, Deskaheh went first to London where he told the British people, “I am on my way to the League of Nations, and stopped off to tell why, to you who care to know. I go because your Imperial Government refused my plea for protection of my people as of right against subjugation by Canada. The Canadian Indian Office took that refusal to mean that it could do as it wished with us. The officials wished to treat us as children and use the rod. This trouble has been going from bad to worse, because we are not children. It became serious three years ago, when the object, to break us up in the end as tribesmen, became too plain for any doubt.”

The Six Nations spokesman remained in Geneva over a year, supported by a Swiss group, the Bureau International pour la Défense des Indigènes. Numerous state representatives supported Deskaheh’s appeal, but British objections prevented a formal hearing by the League of Nations.

A wanted man in Canada, Deskaheh returned to live with his friend Chief Clinton Rickard on the Tuscarora reservation in western New York, where he died in 1925. The Six Nations continue to use their Haudenosaunee passports for international travel to this day.