Canada recently dodged a bullet when the House Democrats negotiated the removal of extended periods of monopoly protection for biologic drugs, such as treatments for Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis, from the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. The Parliamentary Budgetary Officer estimated that these changes, if they’d gone ahead, would have cost Canadians at least $169 million a year.

While Canadians can feel good about this, we were not so lucky in the earlier Canada-EU trade deal. Within the coming decade, intellectual property concessions to Big Pharma made in that deal could start hitting Canadians in the pocketbook. Fortunately, swiftly implementing a universal, national pharmacare plan can more than make up for these projected cost increases.

As a result of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union, brand name drug companies can now obtain up to two additional years of patent protection for their products in Canada. Even before CETA came into effect, new drugs had slightly over 12 years of market exclusivity, i.e., brand name companies had up to a 12-year lead before generic versions would start hitting the shelves. Now, however, that 12 years can turn into 14 under terms protected in the Canada-EU deal.

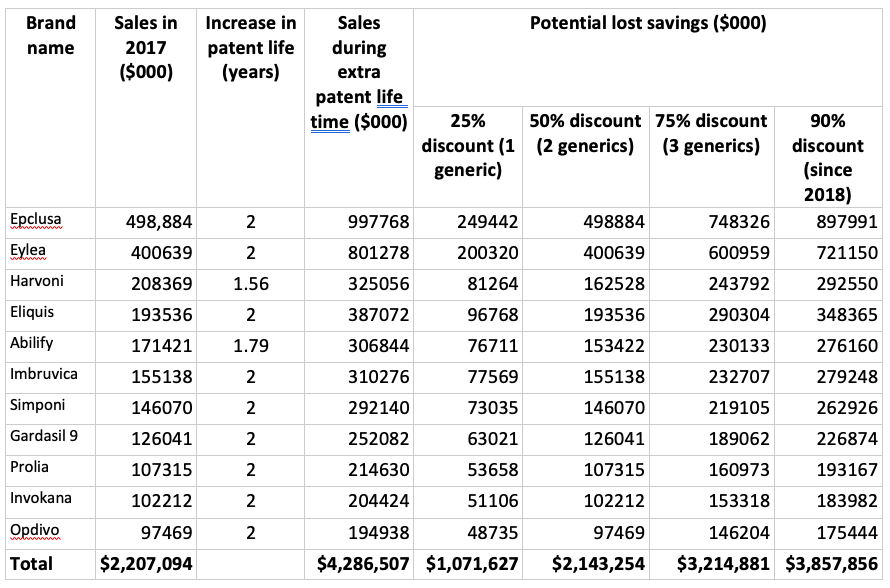

How will those extra two years of brand name patent protection affect the consumer price of prescription medicines in Canada? Out of the 50 best-selling brand name drugs in 2017, 11 qualified for patent extension. From that group, nine got the full two years and the other two got between 1.5 and 1.75 years of additional protection. Collectively these drugs cost Canada $2.2 billion in 2017; assuming sales levels don’t change during the extra patent life of each drug, we can estimate that CETA’s patent term changes will add a maximum of $4.29 billion in costs (see column 4 of the following chart).

Between 2013 and 2018, the first generic on the Canadian market was priced at 75% of the brand name drug. When there were two generics that dropped to 50% and for three generics the price was 25% of the brand name price. Since 2018, generic prices for many drugs have dropped to just 10% of the cost of the brand name product.

Using these different scenarios, and assuming that in the absence of the extra patent life that all of the spending was on generic versions of these drugs, we can calculate the savings we are foregoing on the 11 drugs in the table. As we can see in the final row, if there were a single generic competitor for each of the 11 drugs, the lost savings to Canada from the CETA patent extension would be $1.07 billion. Post-2018, with the even steeper discount in generic prices, lost savings ratchet up to $3.86 billion.

The increase in spending due to longer patent life adds to the already overwhelming case for pharmacare. The prospects of undoing the terms of CETA are virtually nonexistent, so in order to keep spending on medicines under control we need to be able to get a better deal for all of the drugs that we need.

National pharmacare is the mechanism for doing this because there will be a single national buyer for all of the essential medicines. A single buyer can drive a much better deal with companies than the multitude of public and private payers we currently have. If we want to avoid a blowout in drug spending, then pharmacare is a necessity.

Joel Lexchin, MSc, MD, is Professor Emeritus at the School of Health Policy and Management, York University, an emergency physician with the University Health Network, and a CCPA research associate.