In the past year and a half, the Ontario government has demanded that Ontarians sacrifice many vital public services to address an alleged fiscal crisis. But in a report released earlier this week, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) shows that most of the savings from service cuts are not going toward reducing deficits or the debt.

Let’s look at the numbers closely.

Program spending per person—already the lowest in the country—is set to plunge 10 per cent in the next five years. That’s $1,070 less per person per year. Hence, Education Minister Stephen Lecce has been pushing hard to cut the number of teachers per pupil, make high school students take courses online, and cut real wages (after inflation) for education workers. Social assistance recipients have seen their already inadequate incomes decline in real terms. The government elected on an “end hallway medicine” ticket has cut nurses and hospital beds. The list of cuts goes on.

This tight squeeze on program spending is not quickly improving the province’s fiscal situation, the FAO says.

Ontario’s deficit went up by $0.6 billion this year, and by 2021-22, it will still be at $4.4 billion, which is much higher than what it could have been if the savings from painful service cuts were used to balance the books, as the government had promised to do. The same applies to the debt. While the CCPA has argued the provincial debt is at manageable levels for the size of Ontario, the government made the debt into a bogeyman, yet is failing to tackle it head on.

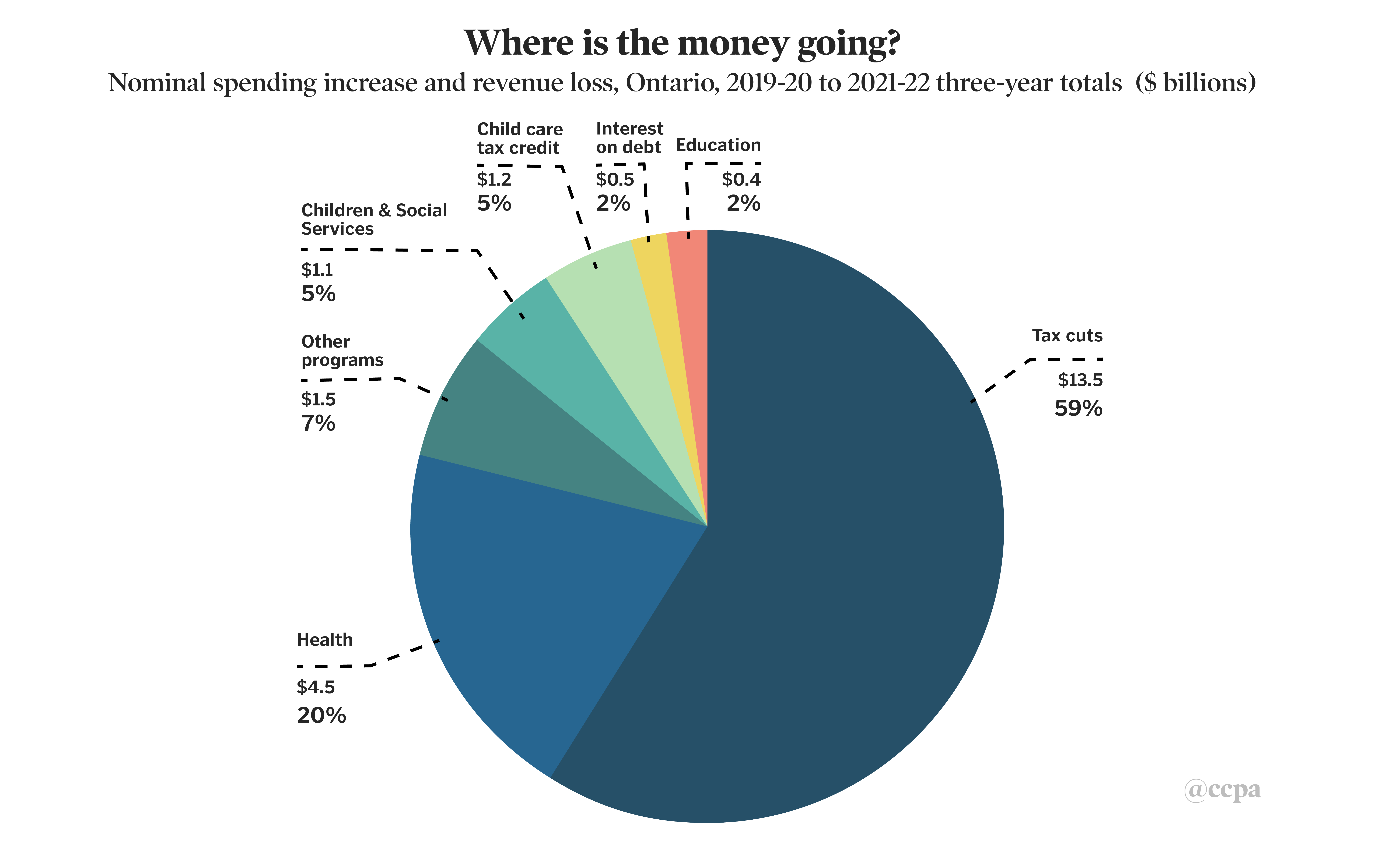

The government is slamming the brakes on spending, yet the fiscal situation is not quickly improving. That leads us to ask, “Where is the money going?”

The answer is tax cuts.

Tax cuts brought in since the PC government was elected 18 months ago are already costing $4.2 billion in 2019-20. Those same tax cuts will cost a further $3.4 billion a year, on average, from 2020-21 to 2023-24. And more tax cuts are coming, the FAO says.

“In the 2019 Fall Economic Statement, the government projected total revenue would reach $165.4 billion by 2021-22, about $2 billion lower than the FAO’s projection. This is largely the result of lower taxation revenue” (p. 12). Lower tax revenue includes the approved $3.4 to $4.2 billion annually as well as “unannounced tax cuts” still to come. The agency estimates the government will cut taxes by an additional $200 million in 2020-21, an amount that will rise each year to $3.8 billion by 2023-24.

The chart below contrasts how much the government plans to spend on tax cuts (revenue loss) with planned (nominal) spending increases, from here to 2021-22, using 2018-19 as the base year. Nearly 60 per cent of the money is going to tax cuts, compared to 2 per cent going to education.

Source: FAO Economic and Budget Outlook, Fall 2019; 2019 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review; 2019 Ontario Budget; calculations by the author.

As the FAO report explains, the nominal spending increases shown in the graph are insufficient to maintain services at present levels, never mind expanding or enhancing them.

Between 2019-20 and 2021-22, Ontario’s population is expected to grow by 5.3 per cent, with an increasing share of seniors, which creates additional pressure on health care. Accumulated inflation for the same period is estimated at 6.2 per cent. To keep up with these increased costs, without cutting services, the province needs to spend $11.4 billion more in the next three years than what it plans to do. It may sound like a lot of money, but it is actually less money than the government is wasting on tax cuts.

The CCPA has analyzed most of these tax cuts, including the replacement of the cap-and trade program by a federal carbon tax, the LIFT tax credit, and changes to personal income tax brackets. We also looked at the child care tax credit, an extremely ineffective way of supporting parents. Low- and middle-income families benefit very little, if at all, from these measures. The “more money in your pocket” jingle is simply a rhetorical trick that preys on people’s economic vulnerability.

On the other hand, all individuals and families, and private sector investors, benefit tremendously from quality education, accessible health care, supportive social services, and adequate infrastructure. That’s where the money needs to go.

Ricardo Tranjan is a political economist and senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Ontario office. Follow Ricardo on Twitter: @ricardo_tranjan.