U.S. Espionage Act charges against WikiLeaks founder may compromise fundamental rights and freedoms at home and abroad

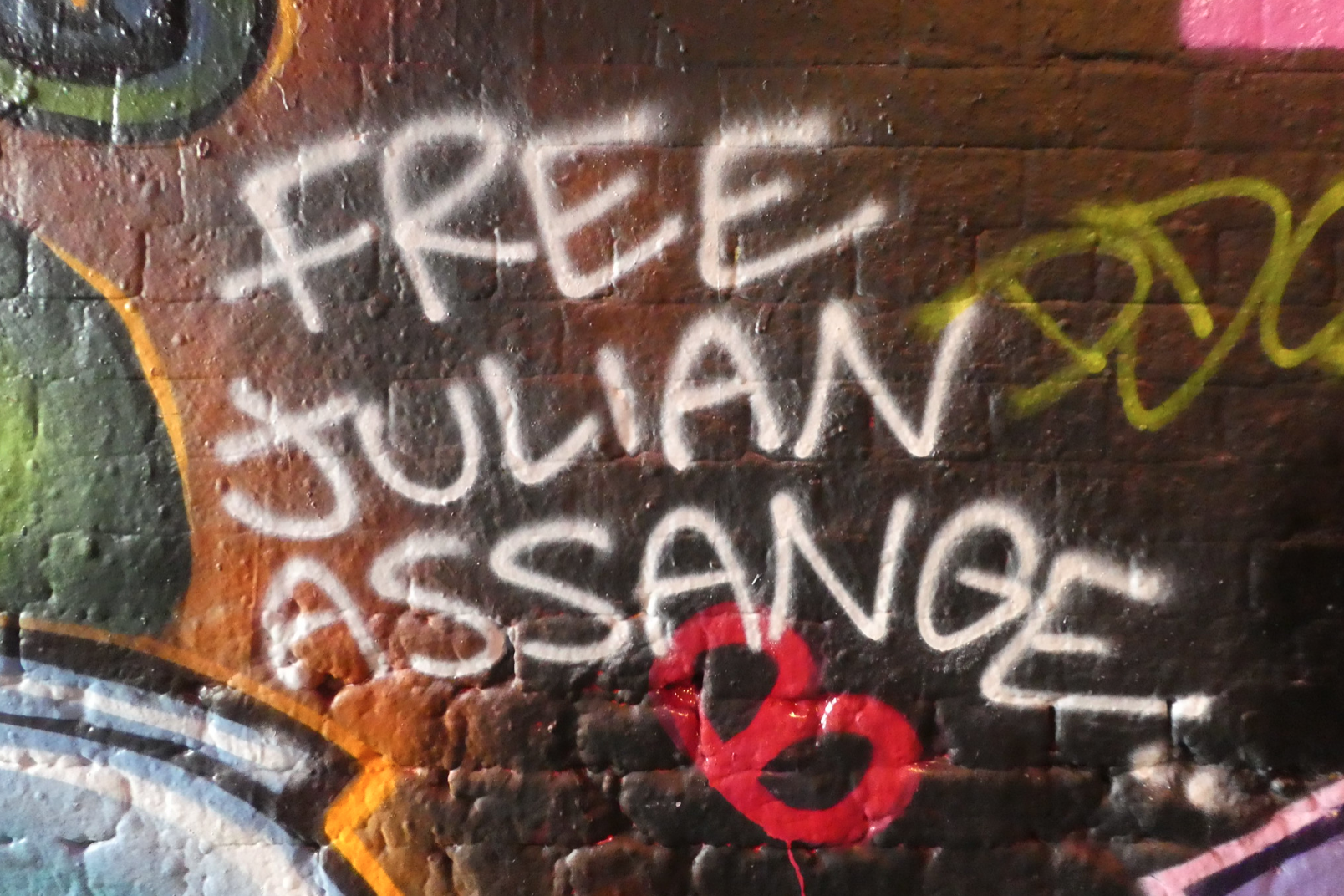

Photo by duncan c, Flickr Creative Commons

In a letter to the New York Times in 1970, British historian Arnold Toynbee said the United States “has become the world’s nightmare.” It turned out they were just getting started. Through its many wars, covert operations and economic destabilizations, the U.S. government has immiserated and killed millions of people in the Global South. Washington’s aim in this carnage, under a thin cloak of liberal internationalism, has been to enrich itself and its Western client states including Canada, Britain and Australia.

Official documents that show the workings of this sordid enterprise are leaked once in a while by brave whistleblowers inside the U.S. empire. The most famous is surely Daniel Ellsberg, who in 1971, a year after Toynbee irritated the U.S. establishment with his judgment, released the Pentagon Papers containing the secret history of the Vietnam War, and became a hero for doing so.

Julian Assange continues this venerable tradition and is paying a high price for it. The WikiLeaks founder is currently being held at the high security Belmarsh prison in the U.K. while he awaits trial to determine if he will be extradited to the U.S. In a November letter to the British government, 60 doctors attested to Assange’s deteriorating physical and mental health and warned he could die in prison. The Trump administration has charged Assange with 17 counts of violating the Espionage Act, introduced in 1917 to criminalize socialist opposition to the First World War. If found guilty, Assange could face up to 175 years in jail.

In 2010, WikiLeaks published hundreds of thousands of classified U.S. military and State Department documents leaked by U.S. army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning, herself jailed in 2013 until former president Obama commuted her 35-year sentence in January 2017. (Manning was jailed again last year for refusing to testify about WikiLeaks before a grand jury, but she has since been released.) The “document dumps that shook the world,” as the BBC described the WikiLeaks cache, showed massive U.S. war crimes in Washington’s Iraq and Afghanistan invasions, including the killing of tens of thousands of civilians by U.S. forces, and the use of death squads, torture and kidnappings in both wars.

“The video was the key document: it shook people up by showing how badly the U.S. forces had behaved in Iraq,” says Julian Burnside, a human rights lawyer based in Melbourne, Australia and a supporter of Assange, who is an Australian citizen. He is referring to the infamous, grainy video revealed by WikiLeaks that showed the crew of a U.S. Apache helicopter in Iraq gunning down 12 civilians including two Reuters reporters. “Ha ha, I hit ‘em,” exults the helicopter pilot.

Six years later, WikiLeaks released “The Yemen Files,” which exposed U.S. complicity in Saudi Arabia’s devastating war on Yemen and Washington’s spying on U.N. officials. But its vast cache of U.S. diplomatic cables would also embarrass the Obama administration on its Libya policy and trade objectives (deregulation) for the failed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with the European Union, among other files. If the government didn’t move then to prosecute Assange it was “because it risked criminalizing subsequent national security journalism,” according to USA Today in a recent article.

The Trump Administration, with its much lower opinion of the free press, had no such qualms. Its prosecution of Assange is “very dangerous” for journalism and human rights, emphasizes Burnside. Even the U.S. mainstream press, which had been attacking Assange for years before the 17 charges were brought against him, seems to agree.

According to Charlie Savage of the New York Times, the Assange case “could open the door to criminalizing activities that are crucial to American investigative journalists who write about national security matters.” Much of what Assange does at WikiLeaks “is difficult to distinguish in a legally meaningful way from what traditional news organizations like The Times do: seek and publish information that officials want to be secret, including classified national security matters, and take steps to protect the confidentiality of sources,” he wrote in May.

The Washington Post’s media columnist Margaret Sullivan called Trump’s indictment against Assange “despicable” in a May 2019 article. She said it was alarming how the case might result in “the architects of secret, and possibly illegal or immoral, government programs [being] the same people who get to decide whether information about them is made public.”

Ben Norton, assistant editor of The Grayzone, a leftist independent media website in the U.S., has said “the U.S. government’s campaign against Julian Assange is one of the gravest threats to press freedoms in modern history.” Norton pointed out that, “in its relentless assault on civil liberties, the Trump administration has the dubious distinction of breaking two records at once: indicting a journalist under the Espionage Act for the first time, and indicting a non-U.S. citizen.”

This last point shows that the Trump indictment is an attack not only on the U.S. press but on journalists all over the world.

Norton blames the mainstream media, including the New York Times, for encouraging Trump’s indictment against Assange by denigrating the whistleblower for years. “This is the ultimate irony,” Norton explains. “The very same institutions and people that stand to lose the most from Assange being thrown in prison are those that helped put the noose around his neck

“As journalists in the U.S. and around the world now stare down the barrel of a gun, it must be said clearly: Everyone who demonized WikiLeaks and Julian Assange put the ammo in that weapon, paving the way for Trump’s historic attack on press freedoms.”

***

Conn Hallinan, an analyst with Foreign Policy in Focus, agrees with Norton and speaks gravely about a major crisis in the media. U.S. news outlets have “covered up the criminal nature of American foreign policy [and] downplayed the major threats to humanity, like climate change and nuclear war,” he says. “Those chickens are coming home to roost. Will it change? Not by itself. Most of the media is owned by people who want to keep the public in the dark.”

In December 2010, Assange was charged with rape in Sweden and released on bail, after which he fled to the U.K. The leftist Correa government in Ecuador granted Assange citizenship and a place to stay in the country’s London embassy so that he would avoid extradition to Sweden to face trial. But this citizenship was withdrawn in 2019 by Correa’s successor, Lenin Moreno, who forced Assange out of the embassy and into the arms of waiting U.K. police. Later in 2019, Swedish prosecutors dropped the rape charge (which Assange denied), stating that “the evidential situation has been weakened to such an extent that there is no longer any reason to continue the investigation.”

Guillaume Long, Correa’s foreign minister, tells me he “believed that Assange’s life, integrity and human rights were at risk for having exposed war crimes,” and that his role “was to uphold and defend Ecuador’s respect for the institution of asylum, at the same time as trying to find a way out of the diplomatic impasse while abiding to Ecuador’s commitments to protect Assange and to international law.”

While Assange was there, the Ecuadorian embassy in London hired UC Global, a Spanish security firm led by David Morales, to provide security for him. Shortly afterwards, according to charges brought against Morales in Spain, the company allegedly started spying on Assange and on Ecuadorian embassy staff on behalf of U.S. intelligence. Ex-employees of UC Global exposed the alleged arrangement to Assange’s lawyers after his arrest, and then to Spanish authorities, who jailed Morales last August. He was released on bail in October and charged with violating both Assange’s privacy and attorney-client privileges, along with bribery and money laundering.

According to an article in The Grayzone, the documents submitted in court, which come from UC Global computers, “detail an elaborate and apparently illegal U.S. surveillance operation in which the security firm spied on Assange, his legal team, his American friends, U.S. journalists, and an American member of Congress who had been allegedly dispatched to the Ecuadorian embassy by President Donald Trump. Even the Ecuadorian diplomats whom UC Global was hired to protect were targeted by the spy ring.”

Morales’s actions appear to have gone beyond spying. According to witness statements seen by TheGrayzone, Morales allegedly proposed breaking into Assange’s lawyer’s office (it was burglarized several weeks later). Witnesses have also testified to there being an alleged proposal to kidnap or poison Assange. Police found two handguns with serial numbers removed and stacks of cash at Morales’s home.

The alleged U.S. spying on the Ecuadorian embassy in London would amount to “a very serious violation of international law and the rules that regulate international diplomacy, as well as a very serious breach of Ecuadorian sovereignty,” says Long. “The fact that the Ecuadorian government has not protested this, or taken any action in response to it, speaks volumes about the new relationship that the Moreno government has established with the Trump administration: one of total surrogacy.”

Since 9/11, the U.S. national security state has been steadily eroding human and civil rights under the pretext of fighting terrorism, to the point where journalism itself is now under threat. Britain and Canada have followed suit, attempting to build all-powerful surveillance states whose policies are increasingly secret and so difficult to question.

“The case of Julian Assange is…the turning point,” warned WikiLeaks editor Kristinn Hrafnsson late last year. “It is the biggest and the most serious attack on journalism and the free press in decades, if not 100 years. If this extradition goes ahead, journalists around the world will have lost so much that it will be very hard, if not impossible, to get back the rights that we had before.”

Asad Ismi covers international affairs for the Monitor.