Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

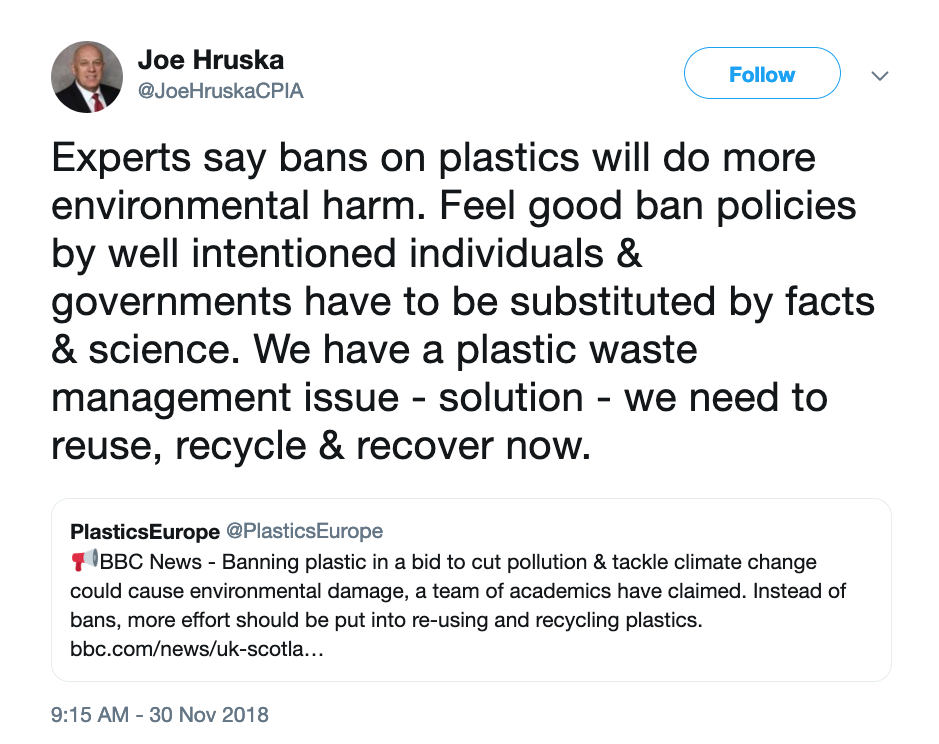

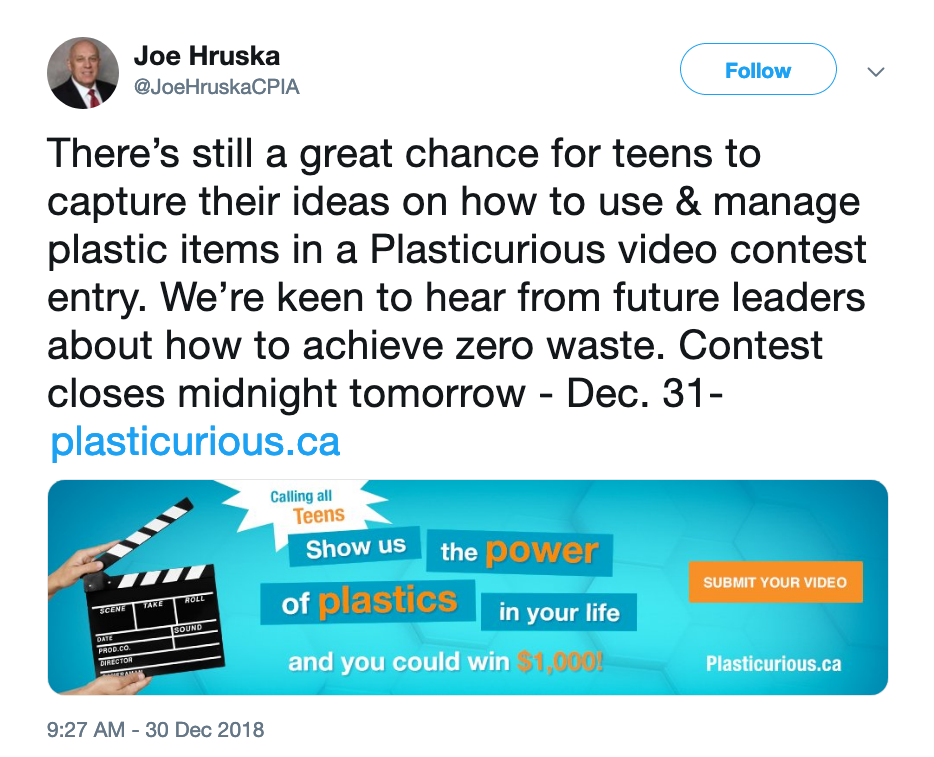

This past November, the Canadian Plastics Industry Association’s VP of sustainability tweeted an invitation to the CPIA’s annual Plasticurious video contest in which teens (ages 14-18) compete for the opportunity to win up to $1,000, “educate themselves and their peers about how plastics power their life,” and have fun learning about an “amazing 21st century material.”[1]

Why just teens? I’m guessing the association knows that older participants would simply be unable to resist submitting renditions of Ben and Mr. McGuire’s famous poolside chat from the 1967 film The Graduate. I picture the scene going something like this:

Mr. Hruska: I just want to say one word to you, just one word. Ben: Yes, sir. Mr. Hruska: Are you listening? Ben: Yes I am. Mr. Hruska: Plasticurious. Ben: Exactly how do you mean? Mr. Hruska: There is a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it? Ben: Yes, I will. Mr. Hruska: Okay. Enough said. Here’s your $1,000. Now go tell your friends.

I’m not kidding: this Dustin Hoffman scene really was the first thing that popped into the heads of most the boomers and gen-Xers I mentioned the CPIA video competition to. Another friend reacted with disbelief: “OMG what?!…. Wow. That is meant in sarcasm right? The tweet?” I had a similar response to the tweet. It’s not like the massive ecological toll from plastics isn’t now daily news.

Plasticurious is ridiculous-sounding. It’s also obviously a play on the term bicurious, which the folks at the plastics lobby have apparently repurposed in a not-so-subtle attempt to appeal to “the youths.” The thing is, young people are already highly plastic-aware or plastic-concerned, [2], plastic-motivated even. The first, promising system launched to tackle the Great Pacific Garbage Patch was dreamed up by Dutch inventor Boyan Slat when he was still a teenager.

So I suspect that while adults are more likely to express skepticism when confronted with the Plasticurious contest announcement, with teens there’s more likely a range of responses that fall somewhere between Boyan’s ingenuity and Ben’s bewildered irritation. Clearly industry feels there’s an opportunity to shape youth opinion of plastics. Otherwise, why bother going to the effort of coming up with a teen-friendly term and a contest to match?

With Plasticurious, industry interacts directly with young people, unmediated by teachers or textbook authors. That said, industry associations also target teachers with supplementary material and reach education ministries directly. Corporate Canada’s involvement in various aspects of education is a topic that’s gained interest and attention, and has been explored in various issues of Our Schools/Our Selves.

Back in the Spring 2002 edition of OS/OS, education professor John Fielding described how he was instructed by Ontario’s previous Conservative administration to include the Canadian Manufacturing Association’s “contributions” to the Canadian economy in his rewrite of the Grade 10 Canadian and World Studies curriculum. More recently, Laura Pinto and Chris Arthur have looked at the financial industry and financial literacy, while the Corporate Mapping Project traces the influence of oil and gas companies in various sectors including education.

Hidden packaging

Industry associations like the CPIA comprise a thin layer of Canadian corporate activity serving the country’s many business sectors with a mix of government lobbying and public relations, much as unions and professional associations provide their members with an opportunity to collaborate on and promote sector interest—but with larger budgets.[3] Having a united and well-funded voice, often in the face of loud criticism—and especially in the absence of it—can certainly support members’ agendas.

The 2005 reprint of Edward Bernays’ seminal 1928 monograph, Propaganda, included an introduction by Mark Crispin Miller explaining how corporate PR emerged from government propaganda efforts of the early 20th century applied in public health contexts such as vaccination drives, and in the Anglo-American effort to demonize foreign competitors like Prussia.[4] Our-side propaganda is not referred to as such because of the negative connotations associated with the term; instead, synonyms like “public education” and “corporate communications” are used.

Large corporations like General Motors, Procter & Gamble and General Electric began to use public relations in the period following World War I, when public opinion became understood as “a force that must be managed,”[5] and public relations practitioners lost some of their stigma as charlatans and hucksters. William Lyon Mackenzie King worked as a spin doctor for John D. Rockefeller before his election as Prime Minister of Canada.

John Stauber, founder of the PR watchdog Centre for Media and Democracy, explains that propaganda, whether beneficial or pernicious, is more effective when received as common sense rather than the result of co-ordinated effort.[6] The “video thought-starters” accompanying the Plasticurious video contest offer ideas about how plastics are being recycled into useful new products. These tips to help contestants get going on their entries align with a core industry talking point—that what’s required to fix the plastics problem is for consumers to recycle more (and ban never). The CPIA seems to have developed its own version of the 3Rs:

“Corporations,” says Stauber, “want us to believe that they are concerned, moral ‘corporate citizens’—whatever that means.”[7] The CPIA hosts neighbourhood cleanups, but this version of stewardship is somewhat questionable: many plastics have no chance of being recovered because the technology does not exist, or because the municipalities on whom the responsibility falls cannot afford to pick up after industry.[8]

Unwrapping the messaging

With the House of Commons passing NDP parliamentarian Gordon John’s private member’s bill to develop a “national strategy to combat plastic pollution in and around aquatic environments” (288 to 0) in December 2018, Canada has an opportunity to address the financing of plastics recovery and its manufacturers’ communication practices.[9] It’s all hands on deck now, much as it was during the earlier acid rain crisis.

In response to growing public and political awareness, the CPIA quickly adapted its website and social media messaging to read “plastics do not belong in our waterways.” The association can be expected to become involved on behalf of board members like NOVA Chemicals, Keurig, Imperial Oil and Dow Chemicals. The extent to which this is further evidence of corporate greenwashing remains to be seen. Industry’s claims of a “circular economy,” prominent in corporate messaging, appear to be aspirational at best, given Canada’s meagre recovery rate of less than 11%.

We’re all familiar with the ubiquity of plastics and the benefits of reduction and preservation that polymers provide. But the consequences of not requiring plastics manufacturers to provide and fund recovery are literally choking the planet, PR and greenwashed messages notwithstanding.

Citizens are pursuing various consumer-based options for, and engaging in debates about, reducing consumption. Reusable bags, and paper or metal drinking straws are all the rage today among teens, boomers and gen-Xers alike. Certainly individuals can play a significant role, but the stakes are too high to stop there. If Canada didn’t require industry to clean up its act, it would be curious indeed.

Jeremy Tompkins is a business librarian who has worked in both investor relations and public relations. He can be contacted at tompkins.jeremy@gmail.com.

References