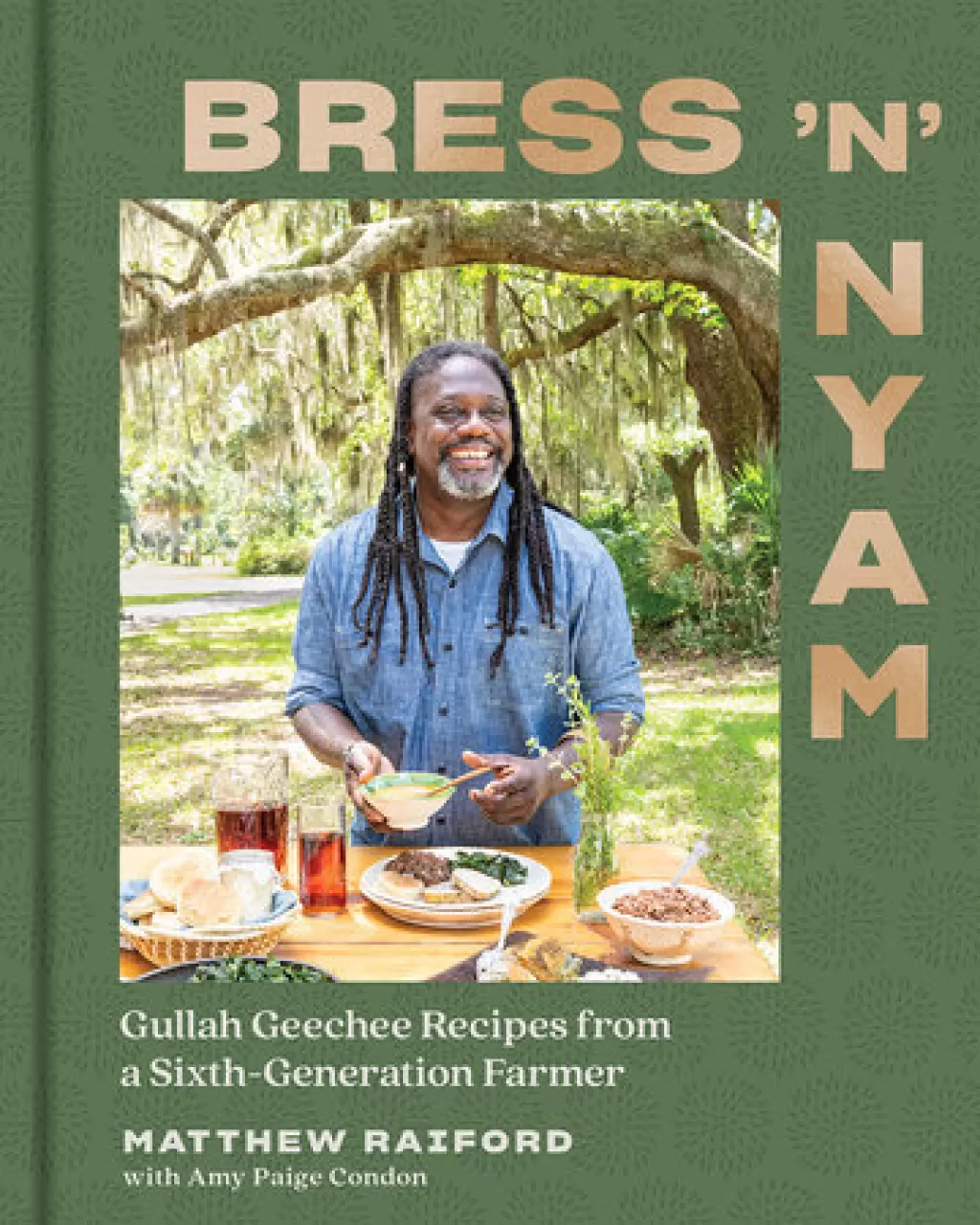

“A cookbook can serve simply as a compendium of recipes or it can offer a story of a people and a place. I am the prodigal son, the custodian of Jupiter Gilliard’s legacy. This book is my origin story.” —Matthew Raiford

It’s rare for one to “read” a cookbook. The texts are meant to be acted upon, to be a resource for meals. Instead, Matthew Raiford’s Bress ‘n’ Nyam: Gullah Geechee Recipes from a Sixth Generation Farmer offers stories and artifacts. Raiford connects ingredients he uses to flavors from his Cameroonian heritage or the stoves his grandmother used before his family was brought to Georgia via the slave trade.

Raiford farms land he owns in rural Georgia with his sister, Althea. Amongst New Zealand hogs (charcuterie), 125 chickens, hens, they have hibiscus and other botanicals and work to diversify the crops on their 40-acre-plus spread by producing 250 lbs of sweet potatoes, alongside onions and turmeric. “I make a basic living because we own this land and don’t pay for housing.”

Raiford is part of a recent tradition among Black farmers who are returning to their ancestral land in recent years to reconnect, perhaps literally, to their roots. He is a renowned chef and sells to restaurants and farmers markets, but acknowledges that many others in his community lack the financial capital to make the change to farming for a living. “Farming is about autonomy, about feeding my family with the first fruits of what we are growing. No farmer should go hungry,” he says.

Unfortunately, farmers on food stamps are common in America, and BIPOC farmers suffer the most from these dynamics. But many Black farmers are taking challenging steps to reclaim their ancestral land in the South, and Raiford is proudly networked with them. Luckily, the resources section of his book shares the contact information and details of many farms in his community, like Sapelo Sea Farms or Oliver Carolina Gold Rice.

“If any of us cousins has a cold or the crud, our moms would call Nana and she would tell them to send us over,” reads the intro to Raiford’s Hot Rum Toddy recipe. Each recipe draws from moments in the author’s life and memories from his ancestry in ways that bring together the current opportunity and challenge for Black farmers: there is so much knowledge, but also much pain.

In the U.S. context, people of colour who choose to farm confront historical inequities and racist policies that complicate farming as a livelihood. White landowners currently control between 95-98% of U.S. farmland.

Media narratives about Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) farmers often revolve around rediscovering their connection to the land, but the stories stop there, as if discovering a love for land is the end of their journey. In the U.S. context, people of colour who choose to farm confront historical inequities and racist policies that complicate farming as a livelihood. White landowners currently control between 95-98% of U.S. farmland and nearly 100% in the Northeast; they also receive over 97% of agriculture-related financial assistance.

While people often cite the increasing numbers of Black farmers every year, there has simultaneously been a decrease in the area of farmland owned by Black farmers due to foreclosures, their inability to secure resources, and racist FDA policies that discriminate against Black farmers applying for loans. Gail Myers, from Farms to Grow, refers to this as the “ongoing overcoming” of BIPOC farmers. This observation ties into a few of my favourite lines in the book: “I knew it would be hard coming back. Not just the farming, but also as a Black man in the South who cooks in a kitchen and works the land. There’s a lot of past to reckon with.”

We also know that land use has a profound impact on the climate crisis. Ironically, BIPOC farmers’ historical lack of access to chemicals and large machinery has contributed to many farmers’ current engagement with regenerative agricultural practices, which have proven long-term climate benefits. The environment is also crucially tied to the ability of BIPOC communities to farm. Chemicals and toxic waste have always been unfairly dumped into poor neighbourhoods, and the ability of the people there to take care of the earth is crucial to both climate justice and racial equity. “We’ve never had a chance to be part of the environment; if farming is the way to do it, then we have to do it,” says Raiford.

Recent developments like public land leasing in Washington State, cooperative solutions designed and led by the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, and land trusts such as the Northeast Farmers of Colours Land Trust support natural land-use practices such as agroforestry and crop rotation. Is there potential to model national land policy around these solutions? These debates are clearly front and centre in President Joe Biden’s administration, as he is ramping up debt relief for Black farmers.

Ironically, Raiford often spoke to me about Black folks leaning on ancestral knowledge about farming and being open to learning from “your own people: learning from nana, not a book.” And yet, Bress ‘N’ Nyam is both.

I highly suggest that anyone interested in American history—or who wants new, delicious meals—read Bress ‘n’ Nyam: Gullah Geechee Recipes from a Sixth-Generation Farmer, which documents and shares recipes from a long line of Black farmers, marking their journey after the Great Migration back to their land.