Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, provinces and territories have implemented eviction bans that protect tenants from the imminent threat of homelessness but do not prevent them from falling in arrears and being evicted once bans are lifted.

Eviction bans contributed to the effectiveness of shelter-in-place emergency orders put in place to ensure everyone’s health and safety, but we still need additional measures to protect renters, during the remainder of the pandemic, and afterwards.

In Canada, adequate housing is recognized as a fundamental human right. This means that our governments must work to ensure that everyone has access to safe, affordable, and secure housing. Without a concerted public policy response to prevent rent arrears, governments will be enabling large-scale evictions. The human cost will be immeasurable. The downstream financial cost will be considerable.

A combination of targeted rent relief supports, a gradual easing of eviction bans, and a reintroduction of rent controls are likely the most effective measures to ensure people remain housed.

Ontario is home to 35% of the tenant households in the country, and to 39% of the workers who lost their jobs or the majority of their hours due to COVID-19. Faced with some of the highest rents in the country, 45% of Ontario tenants spend more than 30% of their income on shelter costs.

Meanwhile, a recent analysis shows Ontario has provided less financial support to households and communities than Quebec, Manitoba, British Columbia, and Alberta (measured as a share of the provincial GDP).

Ontario shares the fifth position in this rank, tied with Newfoundland and Labrador. The province has committed $241 million in support to commercial tenants, but no similar initiative has been extended to tenant households.

A multi-pronged strategy is needed to support renters in Ontario. It’s not too late for Ontario to create an eviction prevention plan.

Tenants’ income insecurity before COVID-19

A large share of tenants was already financially insecure before this global pandemic.

In 2016, there were 1.2 million tenant households in Ontario whose main source of income was employment or self-employment. Of these, 43% (520,000) had less than one month’s worth of income in savings.

In other words, in good economic times, nearly half of tenant households lived paycheque to paycheque. Low wages and high rents are a big part of the story.

Renters earn less than homeowners. In 2018, the median total income of employed Ontarians who own residential property was $61,000, compared to $29,000 for employed Ontarians who rent.

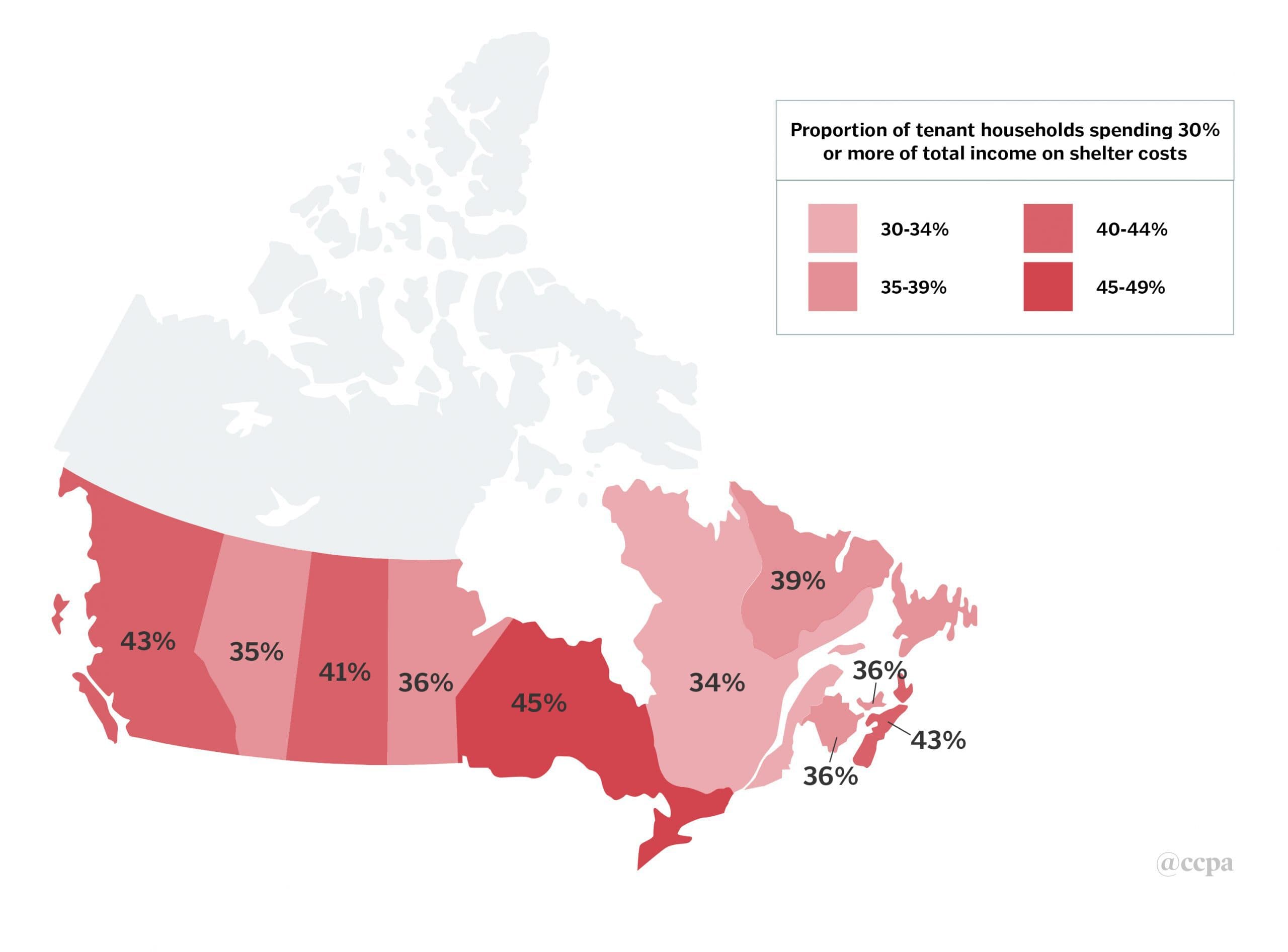

Not surprisingly, tenants spend a large portion of their incomes on shelter costs, and that’s particularly true in Ontario, where 45% of tenant households spend 30% or more of their total monthly income on shelter costs, compared to 40% of renters countrywide.

Figure 1: Share of tenants spending 30% or more of total income on shelter costs, by province, 2016

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016225.

Across Canada, six out of ten of the Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) with the highest share of tenants paying more than the 30% threshold are in Ontario, as shown in Figure 2. For the average rental costs in these CMAs, see Table 1 in the Appendix.

Figure 2: CMAs with the highest shares of tenants spending 30% or more of income on shelter costs in 2016

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016225

Income insecurity during COVID-19

Across Canada the economic lockdown has hit low-wage workers the hardest: half of those who earned $16 or less lost their job or the majority of their hours between February and April, compared to 1% of workers who earned $48 or more.

While the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) is providing crucial income support to millions of workers, it is not a universal program. An estimated 16% of unemployed workers aren’t eligible, and neither are workers whose hours were reduced but monthly earnings remained above $1,000.

For those who get CERB, the $2,000 benefit is equivalent to $12 per hour for full-time work (40 hours per week). In the context of Ontario, this compares to a minimum wage of $14. For 50% of workers who earned from $14 to $16 an hour and lost their job or the majority of their hours, the CERB benefit means a 15% drop in income. For the 36% of workers who earned $16 to $22 an hour, it means a 36% drop in income.

The CERB is a good emergency income support program, but we can’t assume it will allow all tenants to make rent.

The provincial government can ensure that people remain housed during and after the COVID-19 pandemic by developing and implementing an eviction prevention plan which combines:

- targeted rent relief supports;

- a gradual easing of eviction bans; and

- a reintroduction of rent controls.

1. Rent relief

Given the pressures tenants are facing, it’s critical that the Ontario government rolls out a rent relief program. Using data on the impact of COVID-19 on renters and on the cost of rent across the province, we have developed two models that could be implemented quickly and would be easy to administer.

Model 1: Replicating British Columbia’s Temporary Rental Supplement program

British Columbia was early out of the gate in addressing the needs of renters and providing help before arrears had the chance to mount. It announced the B.C. Temporary Rental Supplement program on March 25 and had the program up and running 15 days later. By the end of April, it had received 67,000 applications.

Households have to pass three eligibility criteria to qualify:

- They experienced a 25% drop in employment income as a result of COVID-19, or are in receipt of CERB or EI;

- They are spending more than 30% of their income on rent; and

- Their gross household income in 2019 was less than $74,150 for those without dependents or $113,040 for those with dependents.

Eligible households receive $300 per month if they do not have dependents or $500 per month if they do.

If Ontario simply replicated the same program, it would cover an estimated 185,000 households and cost $70 million a month (see Appendix for details).

Model 2: Emergency Rent Relief Program for recently unemployed and low-earning tenants

Alternatively, Ontario could design an emergency program that also covers working tenants who are struggling to pay the rent. This would ensure that low-waged workers who have provided us with essential services throughout the lockdown are able to benefit from the program in the same way as their counterparts receiving CERB.

In expanding the benefit to workers who have not experienced a reduction in employment income, there needs to be a way to target the benefit towards those most in need. This could be achieved through an income test, similar to British Columbia, but based on current monthly income amounts. The threshold could be a gross monthly income of less than $4,000 for households without dependents and less than $6,000 for those with dependents.

This approach would cover an estimated 340,000 households in Ontario — 190,000 of whom would be in receipt of CERB, a further 84,000 households would be employed but living with incomes below the Low-Income Measure and the remaining 66,000 would have incomes just above it.

The benefit would recognize regional variations in housing costs. The average rent for a one-bedroom unit in Ontario ranges from $550 in South Dundas to $1,360 in Toronto. To recognize that renters need different levels of help depending on the housing market they live in, the program could base the benefit amount on 50% of Median Market Rent (MMR) in their area.

Households without dependents would receive 50% of the MMR for a one-bedroom unit (which, across Ontario, would amount to an average payment of $550). Those with dependents would receive 50% of the MMR for a three-bedroom unit (with an average payment of $730).

With more people eligible and a higher average benefit amount than the B.C. Temporary Rental Supplement, this model would cost more to deliver, at an estimated $210 million per month.

A crucial aspect of either program is that payments would need to be retroactive. Ontario’s lockdown began in March, two rent payments ago.

2. Eviction ban

The Ontario government enacted a timely eviction ban that provided tenants across the province with some peace of mind. The next step is to formulate a thoughtful and reasonable approach for the gradual easing of the ban.

The reopening time frame is highly uncertain, with public health experts warning about the possibility of a second or even a third wave of COVID-19 infections that would trigger the re-enactment of lockdown measures.

As the next wave of COVID-19 could come during our Canada’s coldest months, it will be even more important to ensure that Ontario renters are not evicted, nor receive a threat of such action.

The Ontario government should keep the eviction ban in place for the time being, while initiating an open policy discussion on the conditions that will need to be in place for its gradual easing.

3. Rent control

It also makes little sense to allow rents to increase through a health and economic crisis.

Ontario has no rent control on vacant units and properties occupied after 2018. Annual increases in all other units are capped at the rate of inflation or 2.5%, whichever is lowest. Landlords can apply for authorization to impose above guideline increases if fixed costs increase significantly or capital improvements are made.

In normal times, the lack of strict rent controls increases the financial insecurity of tenants who see housing costs increase at a higher pace than their income. In the present context, disproportionately high rent increases could put tenants at risk of evictions.

While some landlords will not raise rents in the next while, some landlords will.

A large and growing share of landlords are real estate investment trusts that have no direct contact with tenants; they directly profit from tenant turnover since the lack of vacancy controls allows them to increase rents well above the guideline for occupied units. On the other hand, only a small number of landlords are individuals and families who rent out a part of their own homes and have a relationship with their tenants.

A government-mandated temporary freeze on rent increases would be the best way to ensure fair treatment for all tenants and landlords.

Reopening without evictions

There is a lot of pressure to gradually phase out of the shelter-in-place orders, so that people and communities can resume their daily activities.

As we think about easing restrictions, Ontario needs an eviction prevention plan. Without it, there is a significant risk that renters across Ontario could lose their housing.

The rent relief programs proposed above would provide increased financial security to between 185,000 and 340,000 households, helping individuals and families to focus on staying healthy and gearing up to go back to work.

Public funding invested in a rent relief program would find its way back not only to landlords but to the economy writ large. If tenants stay solvent, they will spend future employment income on goods and services. If they become indebted, a share of their wages will go to paying interest and principal repayments instead of going to local shops, decreasing economic activity in the province. Rent relief makes economic sense, too.

A rent relief program is a necessary measure; but to ensure housing security and prevent homelessness, it needs to be accompanied by other actions, namely maintaining the evictions ban and reintroducing rent controls.

The evictions ban has only delayed the worst impacts of the pandemic on renters. The province has bought itself some time to implement a solution—tenants can’t afford to wait much longer.

Appendix

Table 1. Average Rental Costs (2019) in CMAs with highest shares of tenants spending >30% of income on shelter [table id=15 /]

Source: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016225 & CMHC Rental Market Survey 2019.

We used the Labour Force Survey Public Use Microdata File (April 2020) to calculate the share of Ontario workers in each industry-occupation who are eligible for CERB. We imputed these probabilities into the 2016 Census Hierarchical File, randomly assigning workers to the CERB control condition. We used this dataset to estimate the number of households who would be eligible for the proposed rent relief programs. Using CMHC data on median market rents, we calculated the projected cost for each program.

Table 2: Comparison between the B.C. approach and proposed Emergency Rent Relief Program [table id=16 /]