Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Before it was an entrenched globalized system, it was an idea.

Neoliberalism is a term that we use to describe the system dreamt up by right-wing economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. Those thinkers, operating in an era of class-compromise social democracy and competition with communism, were proponents of an economy structured entirely around profit—one where the invisible hand of market incentives guided every social interaction.

In this dream, the government needed to “get out of the way” of private industry—mostly by getting rid of pesky regulations, government programs, public institutions, and taxes. There was, in the eyes of neoliberals, no task that private capital couldn’t accomplish more efficiently than the state—not education, not health care, not the post office, not anything.

For a long time, that’s all that it was—a dream. Thinkers like Friedman were certainly swimming upstream. From the 1930s to the 1980s, Keynesian economics dominated the field, with the view that governments have an important role to play in stabilizing the economy through spending programs, especially during economic downturns. Policy-makers, for the most part, believed this as well. That period represents the most significant—although still limited in very important ways, especially around race and gender—expansion of the welfare state in history. For the neoliberals, it must have felt like they were out in the wilderness.

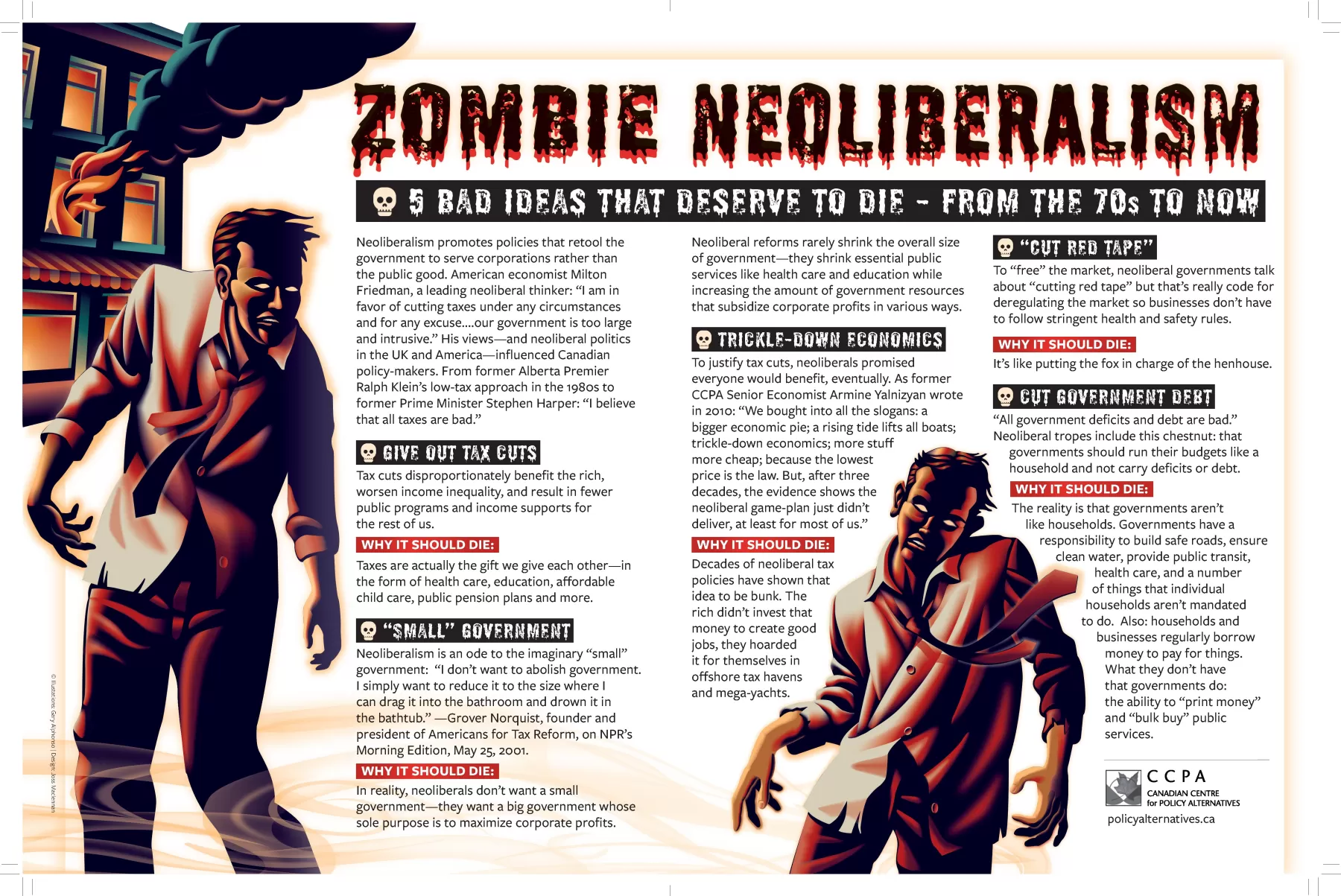

Neoliberals believe that the state should only exist to maximize corporate profits. In practice, this meant a fundamental restructuring of the role of government in the economy. Policy-makers shifted the tax burden from corporations onto individuals, sold off public companies (think Petro-Canada, CN Rail, Air Canada, and more), and introduced market reforms into the institutions that remained public.

Neoliberal reformers came up with myths and tropes to bring the public onside, to justify their decisions to give an ever-increasing share of the pie to the ruling class.

They said government debt was out of control, that creditors were going to pull out and collapse the Canadian economy. Organizations like the Canadian Taxpayers’s Federation—helmed by future Alberta Premier Jason Kenney—set up “debt clocks” that broke down government debt by the Canadian population, as if government debt had to be paid back by every individual. The numbers certainly looked scary!

They said that environmental regulations were unnecessary hindrances to the market and should be abolished—that any real environmental problems would be better solved by increased (voluntary, of course) coordination in the private sector to address them.

They said that labour unions had outlived their usefulness and that workers would be better off negotiating directly with their employers as individuals instead of having the power of collective bargaining.

They said that if we increased the minimum wage, then the cost of everything would skyrocket—so the only way to keep prices low was to have a perpetually impoverished underclass of workers performing minimum wage jobs. They also told us those workers were mostly teenagers.

They said that if we cut taxes on corporations and the rich, then those wealthy individuals and institutions would use the money to invest in job creation. They said the wealth would trickle down to the rest of us.

They told us a lot of things and none of them turned out to be true, really. The tropes that they created were just retroactive justifications for their decision to abandon the class-compromise of the Keynesian era.

Today, those lies are increasingly untenable. We know, clearly, that wealth does not trickle down, that breaking unions is bad for the working class, that corporations will not self-regulate, and that minimum wage increases are good for the economy. We know that government debt doesn’t behave like household debt.

We’re in something of an in-between stage, with an emerging consensus that neoliberalism failed, but without a system to replace it. We hope that the arguments you find in this edition of the Monitor will be a small contribution to nailing neoliberalism’s coffin shut—and making space for what comes next.

Download the PDF of the Monitor