Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Canada has a new poverty reduction strategy. Released in August, Opportunity for All establishes for the first time a target for reducing poverty in Canada, an official poverty line, and a framework and a process for reporting publicly on progress. These are important policy wins, but today – on the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty – they provide little comfort for those struggling with inadequate food, housing, and precarious work.

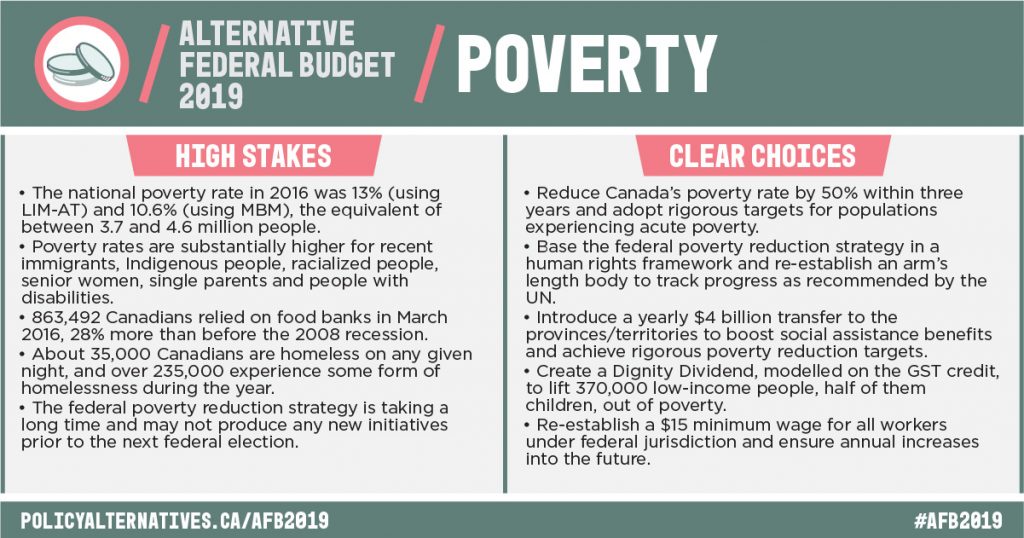

Opportunity for All does not include any new investments in the programs needed to achieve the strategy’s goals. Indeed, Canada’s new plan is more of a framework than a strategy to accelerate poverty reduction. A strategy implies a plan to get from where we are to where we want to go – and, crucially, the resources to back it up.

From measurement to action

It is past time for the federal government to develop and implement, with the provinces and territories, a comprehensive federal action plan to end poverty for all Canadians and significantly close the income gap. Such a plan requires more ambitious targets and timelines than those proposed by the government and greater investments in our social safety net and essential services.

For more than two decades, the Alternative Federal Budget has provided a blueprint for sustainable and equitable growth in Canada and a more caring society. This year, we present several policy recommendations designed to eradicate poverty within a decade and ensure that everyone’s income is raised to at least 75% of the poverty line within two years.

Modernizing and enhancing Canada’s income security programs is essential to achieving these targets. That includes:

1. Additional support for provincial-territorial poverty reduction efforts and boosting social assistance benefits

The provincial social assistance system is a shadow of what it was during the early 1990s. The purchasing power of welfare benefit rates has plummeted and new rules have made assistance harder to get. The good news is that every province and territory in Canada now has a poverty reduction plan (at some level) in place or in development. The bad news is that some plans have expired and have yet to be renewed.

The AFB introduces a new federal transfer payment to the provinces and territories, tied to helping them achieve their poverty reduction targets. This transfer will be worth $4 billion per year – in addition to funds transferred under the Canada Social Transfer.[1] The intent of this new transfer is to ensure that the bulk of these funds helps provinces and territories substantially increase social assistance and disability benefit rates and eligibility.

The AFB also calls on the government to reinstate minimum national standards for provincial income assistance through conditions (to ensure that social assistance is accessible and adequate), with specific consideration for vulnerable populations (persons with disabilities, lone‐parent families, immigrants, and women).

2. Reform of the EI program by easing eligibility requirements, extending benefit durations, and increasing benefit rates

Employment insurance (EI) is a vital part of Canada’s social safety net, but successive federal governments have made the program less equitable and much harder to access. A social insurance program should dampen the effects of labour market inequality; the current design of EI amplifies it.

The Liberal government rolled back several Harper era reforms including the definition “suitable work”, reducing the waiting period for benefits, and introducing more flexible parental leave options and a new Parental Sharing Benefit. They have also increased funding for employment and training programs managed by the provinces, territories and Aboriginal labour market organizations. These changes are welcome, but no substantive action on fundamental reform has been taken that would update the system for today’s labour market and explicitly address issues of access and systemic bias.

Immediate action is needed to expand access to the program and to enhance the support on offer to the unemployed, new parents, caregivers, or workers coping with illness. This includes instituting a lower uniform entry requirement for regular and special benefits, lower thresholds for accessing benefits of maximum duration, higher income replacement rates, and a higher maximum insurable earnings (MIE) level.

While EI has a supplement for low-income families with children under 18, there is no supplement for those without children. Introducing a benefit floor of $300/week would be a meaningful step towards reducing inequality for low income workers.

3. Further improvements in benefits for seniors and people with disabilities

The CPP and OAS are cost-effective and sustainable programs, but they are falling short of their goals. After a steady decline in rates of poverty among seniors over several decades, we are now seeing an increase. In 2015, 7.8% of seniors (425,000) lived in poverty (MBM – Census). And the future looks troubling. Just one in four workers (37%) belonged to a workplace pension plan in 2016, down from a high of 46% in 1977, while private savings are at all-time lows.

The Liberal government made several positive reforms in 2016, increasing the GIS top-up paid to the lowest-income single seniors by as much as $950 annually and eliminating the planned increase in the age of retirement. Also, the federal government and all provinces except Quebec reached an agreement on modest pension enhancements[2].

Moving forward, the AFB would increase the GIS top-up for singles and couples and increase and index the basic earnings exemption for employment income. Given the potential problems that higher CPP benefits pose for accessing the GIS top-up, the AFB also expands the income exemption for determining eligibility by exempting the first $1,500 in CPP benefits. It calls on governments to raise the CCP replacement from 33% to 50% of earnings and extend the child rearing and disability dropouts to the enhanced benefit.

The CPP Disability program also demands attention. The AFB proposes to increase the monthly benefit rate, expand the definition of disability, and loosen the eligibility requirements to ensure more people with disabilities qualify. Another significant step would be to make the federal disability tax credit refundable (rather than nonrefundable), so that like the GST credit, it would go to all people who need assistance, even those whose incomes are so low that they don’t pay income tax.

4. A real poverty reduction plan

The most ambitious plank in the AFB’s poverty reduction plan is a new “Dignity Dividend.” Modelled on the GST Credit, it would offer a maximum of $1,800 per adult and child, targeted to those below the poverty line regardless of family type. Benefits would be reduced at rate of 15%, excluding the first $2,500 of income. In combination with the social assistance transfer, these two measures would reduce Canada’s poverty rate by 11%.

Taken together, all these actions would strengthen Canada’s social safety net considerably and create a more flexible and effective platform for reducing poverty. Real ambition, a real plan, a real opportunity to eradicate poverty in Canada.

Katherine Scott is a Senior Economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow her on Twitter @ScottKatherineJ .

[1] Currently, the federal government transfers $13.3 billion per year to the provinces and territories under the CST. Under the current formula, federal transfers will continue to decline as a share of GDP over time.

[2] The CPP retirement benefit rate, frozen for 50 years at 25% of average lifetime pensionable earnings, will gradually rise to 33.3% by 2023.