With less than two weeks until Canadians head to the polls, we’re turning our attention to one of the key topics that impacts affordability for young voters: post-secondary education. While there are a number of different aspects to the debate, this post focuses on the different approaches to affordability taken by the Liberals, the Conservatives, the Greens and the NDP.

Generally, the parties have each chosen to target one specific approach to making education more affordable, as part of the focus on families: savings, debt repayment, or addressing cost at source. Each rests on a set of assumptions about who pays and how we pay for post-secondary education, and a different interpretation of what “affordability” means.

One approach to affordability is to support individuals and their families in saving more money to spend later on education costs, specifically through the publicly-funded components of the Registered Education Savings Plan—the Canada Education Savings Grant (CESG), Additional-CESG (A-CESG), and the Canada Learning Bond (CLB).

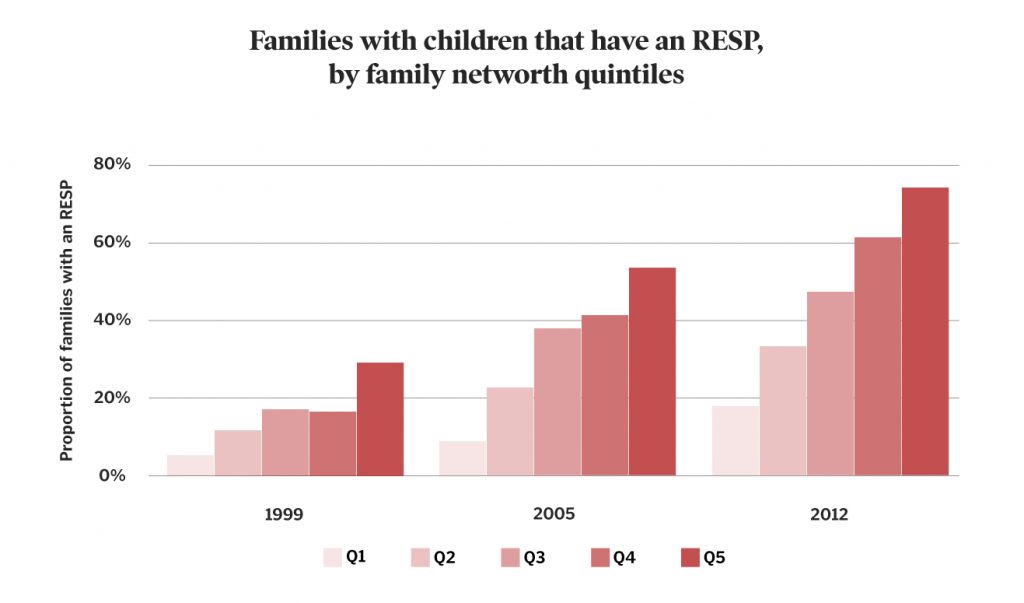

Although technically it is a savings mechanism that’s open to anyone who wants to invest in a future student’s post-secondary education, since the program’s inception in 1972, RESPs have disproportionately benefited higher-income earners. This was demonstrated by Kevin Milligan in 2002, again in 2008, and by the Parliamentary Budget Office in 2016:

More recent analysis from Statistics Canada found:

Families in the top quintile held $2,388 more in RESPs than those in the bottom quintile in 1999, on average. By 2012 this gap had increased to $13,843. In relative terms, the average dollar value of RESP holdings was 4.2 times higher among families in the top income quintile than among those in the bottom quintile in 1999. In 2012 this ratio stood at 7.7.¹

Sources: Statistics Canada; Survey of Financial Security 1999, 2005, 2012; Statistics Canada Custom Tabulations. Note: Q1 is the lowest net-worth quintile; Q5 is the highest.

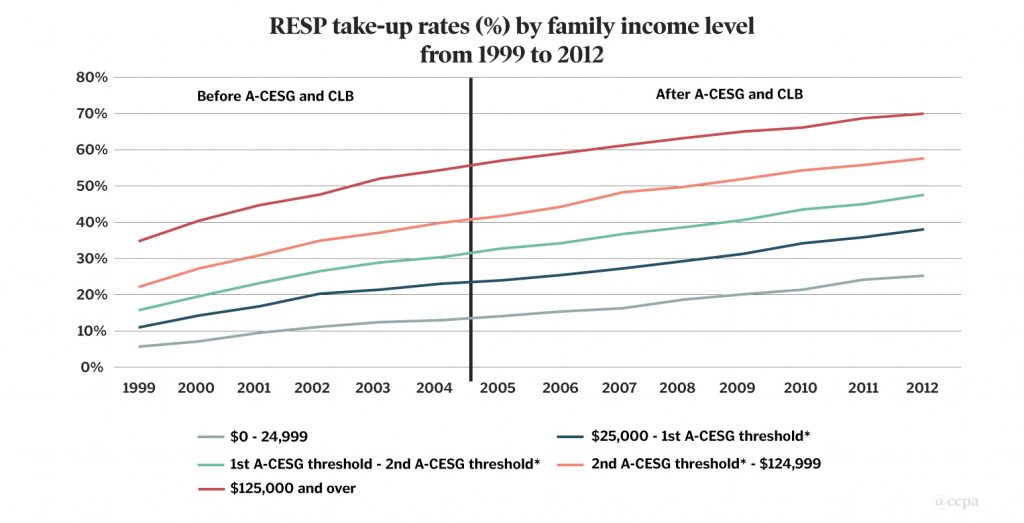

While the introduction of the CESG in 1998 and A-CESG in 2004 (geared towards low- and middle-income families) resulted in additional take-up of RESPs among lower-income Canadians, it also meant a growing share of public money is disproportionately benefiting wealthier families who are in better financial position to invest and therefore take advantage of the matching government funding. (The CLB, introduced in 2004 for lower-income families, can amount to a maximum of $2,000 over the life of the investment.) An internal evaluation of the CESG found that, even with these more targeted add-ons, “The program remains skewed toward higher-income families, despite newly added elements such as the Canada Learning Bond designed to direct more money to the less well-off.”²

Sources: 1% sample of families living with children (CRA T1 income tax data linked with CESP administrative data with 545,274 observations from 1999-2012). This sample of families living with children represents 85% of CESP expenditures. * Annual A-CESG thresholds are used, which are also CCTB thresholds. For years before the introduction of the A-CESG, CCTB thresholds are used. The $25,000 and $125,000 thresholds are adjusted for inflation each year (real $2012).

More specifically, “over $400 million in grants (or 49% of all CESP expenditures) were distributed to families with a household income of $90,000 or more in 2013, of which $280 million (or 32% of CESP expenditures) went to families earning $125,000 or more.”

To this already structurally regressive savings mechanism, the Conservative plan would increase the government’s annual CESG contribution from the current maximum of $500 to $750, bumping up the lifetime contribution from $7,200 to $12,000. It might increase program participation among some lower- and middle-income Canadians who—in spite of stagnant wages and competing expenses like housing, food, child care and transportation—can somehow still afford to put aside some money for their childrens’ education. But it would continue the existing pattern of benefiting wealthier Canadians even more.

Another approach to addressing post-secondary affordability is to change the repayment parameters of the debt amassed from pursuing a degree or diploma. This policy is rooted in the assumption that debt is inevitable, and the role of governments is to help individuals mitigate the burden. Of course, student debt is in no way inevitable but is a direct result of rising tuition fees that are perfectly within the power of governments to change.

In post-secondary education, this debt management approach can take the form of debt forgiveness or making debt interest-free, implementing a fixed grace period before repayment commences, or making repayment contingent on a minimum income. It’s a form of after-the-fact assistance designed to provide some relief to graduates and quell public concern about the rising up-front costs of higher education, but given the uneven nature of these policies and the way in which they can change or be cancelled mid-stream, it’s contributed to an extremely complicated system of student aid programs that still leaves graduates with significant levels of debt years after their last day of classes.

The fact that tuition fees are largely increasing has everything to do with declining levels of public (federal and provincial) support, resulting in an increasing institutional reliance on the costs for higher education being downloaded onto students and their families. The Liberal plan does increase access to federal grants, which is great—for those who qualify.

Rather than addressing the root cause of the high cost of education, the Liberal plan focuses on debt repayment. Specifically: extending the six month grace period (post-graduation) to two years interest-free, pausing payments if one’s income falls below $35,000 (up from the current $25,000), and allowing graduates to suspend interest accrual on loan repayments until their children turn five.

In effect, graduates who are also new parents will be given the opportunity to take a break from student loan repayment and switch to paying often exorbitant child care fees up until their children are school-aged, at which point student debt repayment will resume, provided their income remains above $35,000. Not only does this pause-and-resume flexibility add an additional set of considerations to a student aid system that’s notoriously difficult to navigate, it extends the life of the debt well into adulthood for graduates (along with interest accrued along the way). In this case, affordability is not about actually eliminating or reducing debt; instead, it’s redefined as allowing graduates to kick the debt further down the road depending on specific life circumstances.

The last approach this post looks at is to reduce or eliminate the individualized cost of a post-secondary education at the source, and to reduce or eliminate the debt that has accumulated to this point. The NDP and the Greens have included variations of this strategy in their respective platforms, though to this point the NDP’s plan has not been fully costed.

Tuition fees are not the only cost of post-secondary education, of course, but they are the first significant cost that students encounter, and they are also the portion that has exploded since the 1990s. They also are, at least to some degree, influenced by provincial and territorial governments, which can legislate freezes, caps on increases, or rollbacks—though if universities and colleges are not compensated by provincial governments for a reduction in their expected income from tuition fees, they may reduce expenditures by trimming costs, or increase revenue by charging students additional compulsory fees (or deregulate fees for international students).

There are significant individual and social returns on investment in higher education, though these may not feature prominently in campaign literature. However, education as a job requirement certainly does. There is also broad recognition that the financial burden of post-secondary education on students is substantial, resulting in $19 billion in federal student debt alone, with rising default rates.

Research has also demonstrated that this debt burden comes with longer-term ramifications for students including fewer savings, less disposable income, and the postponement of major life decisions like home ownership, buying a car, saving for retirement, or having kids. This also impacts society more generally, in part because student debt repayment means there is less money going into local economies.

The Greens have indicated they would allocate $10 billion to post-secondary institutions and trade schools, eliminate university and college tuition fees, and forgive student debt held by the federal government for graduates who are unemployed or earning less than $70,000. They would, if elected, also phase out the CESG and CLB (which presumably, with fee elimination, would no longer be necessary).

The NDP have committed to a more gradual approach (similar to what Newfoundland and Labrador did in the early 2000s). They have pledged to work with the provinces to “cap and reduce” tuition fees, eventually “making post-secondary education part of our public education system,” and eliminate interest on existing federal student loans, which will gradually be replaced with more non-repayable Canada Student Grants.

Each party’s plan to address the cost of post-secondary education is rooted in a different approach: the Conservatives’ is an enhancement of an individualized, targeted form of assistance that remains based on a user-pay model, that provides assistance to lower income families if they have spare money to save. The Liberals’ plan also focuses on the individual’s accumulation of debt, but directs its attention to helping people manage the money they owe, with flexibility tied to income or life circumstance. The NDP and Greens focus on a more collective approach to post-secondary education accessibility by front-end loading the public investment rather than addressing debt on an individualized basis after the fact. This approach can eliminate or reduce financial barriers to higher education by removing the need for student loans from the outset. Again, while these plans all aim to address the affordability of post-secondary education, the variation in approach reveals very different interpretations of what “affordability” means.

¹ Figure 1 is adapted from Federal Spending on Postsecondary Education, Figure A-5, page 38: https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/Reports/2016/PSE/PSE_EN.pdf

² Figure 2 has been adapted from Canada Education Savings Program (CESP): Summative Evaluation Report, Graph 3, page 19: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/edsc-esdc/Em20-37-2016-eng.pdf

Erika Shaker is Director of Education and Outreach at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and on Twitter at @ErikaShaker.

The CCPA has done extensive research and analysis on a wide range of federal policy issues, most notably through our annual Alternative Federal Budget. As we head towards the October 2019 federal election, we’ll be sharing our independent, non-partisan analysis and fact-checking of campaign promises and platforms from all the major parties.