Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

I’ve speculated in earlier posts that many of the promises made by parties during the federal election campaign were expensive, and I was curious about how they’d pay for them. Of course, there are always three choices: run a larger deficit, raise taxes or cut services. The NDP and the Greens primarily pledged to raise taxes. The Liberal’s platform chose to run a larger deficit. The Conservative platform, we found out on the Friday before a long weekend, plans to close unnamed loopholes by “closing the tax gap”—the difference between what people and corporations should pay in taxes and what they do pay. The Conservatives also plan to make cuts operating expenditures and infrastructure.

Cuts to the public service in order to balance a budget is nothing new. Comparing the current Conservative platform—by shifting the proposed cut dates back ten full years—with cuts made by the federal government a decade ago at that time, shows that the 2020 plan is very near the scale of the cuts made between 2010-2012. This comparison provides an opportunity to examine potential impacts and job losses. Neither table adjusts for inflation meaning the figures from 2010-2012 would be larger in today’s dollars. Table 2 also doesn’t incorporate a further round of cuts that were the results of the annual Strategic Reviews that were happening between 2007 and 2010, but whose impacts continued into the future.

Table 1: Proposed Conservative public service cuts

| Fiscal Measure | 2020-21 ($mil) | 2021-22 ($mil) | 2022-23 ($mil) | 2023-24 ($mil) | 2024-25 ($mil) |

| Maintain 2020-21 staffing levels in the Federal Government | 0 | 48 | 211 | 351 | 558 |

| Maintain non-personnel operating expenses at 2019-20 levels | 823 | 1,828 | 2,861 | 3,920 | 5,005 |

| Source: Conservative 2019 platform | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Table 2: 2010-2012 federal government cuts

| Fiscal Measure | 2011-12 ($mil) | 2012-13 ($mil) | 2013-14 ($mil) | 2014-15 ($mil) |

| 2010 Personnel budget freeze | 900 | 1,800 | 1,800 | 2,000 |

| 2012 Strategic and operating review | 1,472 | 3.061 | 5.142 | |

| Source: Clearing Away the Fog, 2012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Comparing table 1 and 2, both plans target a freeze of some sort on the personnel budget. That’s not surprising as the salaries and benefits line is almost always the largest in any department. The 2010 budget freeze locked in the absolute value of the salaries and benefits line itself, so while wages would still grow by roughly 1.5% a year based on collective agreements, the total amount paid to employees couldn’t go up. This meant that departments would have to cut 1.5% of employees annually to maintain the cap or transfer that money in from another budget line in order just to maintain their staffing levels.

The proposed 2020 cuts wouldn’t freeze the budget line itself, but would instead freeze the number of employees. This wouldn’t necessitate cutting a certain percentage every year, but it would stop departments from hiring in order to meet increased demands or even to get standards up to where they should be, but aren’t presently. If more pay specialists needed to be hired to help clean up the ongoing Phoenix pay debacle or more CRA phone operators needed to be hired to reduce atrocious waiting times, those changes wouldn’t be possible. It might also require cuts in other parts of a department in order to meet requirements for staff expansion.

The second line of cuts in both of the two tables, related to operating expenses, is remarkably similar both in size and likely result. In both cases, the cuts would ramp up to roughly $5 billion a year and they would target non-personnel expenses in a department’s budget. The “Strategic and operating reviews” in 2012 were supposed to target “back office” savings, not dissimilar from the proposed 2020 cuts for non-personnel costs like consultants or rent. In the 2012 Strategic and operating reviews, departments had to submit plans for 5% and 10% cuts to their departments. Some departments were forced to implement their 10% plan, others their 5% plan and some departments saw no cuts at all. Departments found it very difficult if not impossible over the 2010 to 2012 period not to shed staff as a way to reach the cuts demanded by the three overlapping programs of cuts.

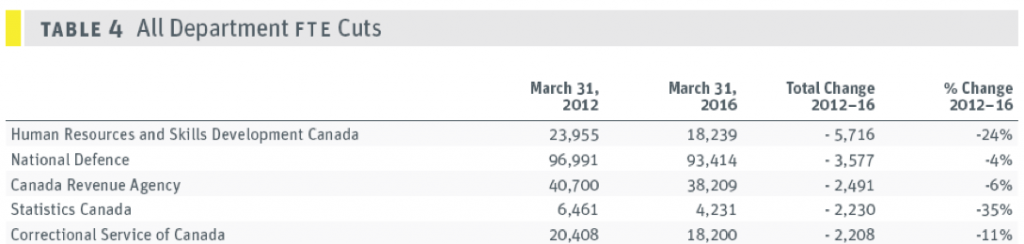

How budget cuts played out as job cuts in various departments is illustrated in full detail in my re-cap report The Fog Finally Clears, published in 2013. Across the entire federal government, over 28,000 full time equivalent (FTE) positions were cut. It’s impossible to say whether the 2020 version of these cuts would play out similarly or not, but the table below illustrates the largest losses by department over that period.

Source: The Fog Finally Clears, 2013

In the cuts a decade ago, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, now Employment and Social Development Canada, was hit the hardest, losing almost 6,000 FTEs. The Department of National Defence, for its part, lost 3,577 positions, although this was all on the civilian side and not the military side. The Canada Revenue Agency, Statistics Canada and Corrections Canada all lost over 2,000 FTEs. Several of these departments are still recovering, particularly StatCan which lost almost a third of its FTEs.

As stated earlier, it’s impossible to predict if the 2020 version of these cuts would have a similar impact. But comparing the plan against the scale of cuts made federally between 2010-2012 shows just how high the stakes are for the public service and all those who rely on it.

David Macdonald is a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter at @DavidMacCdn.

The CCPA has done extensive research and analysis on a wide range of federal policy issues, most notably through our annual Alternative Federal Budget. As we head towards the October 2019 federal election, we’ll be sharing our independent, non-partisan analysis and fact-checking of campaign promises and platforms from all the major parties.