Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

The federal government is introducing (through Bill C-2) a new top bracket for Canada’s richest, which reflects what we have been saying for years in the Alternative Federal Budget. However, the government’s plan to use the resulting revenues to reduce the tax rate for those in the second bracket isn’t particularly progressive because it transfers the largest benefit to families making $98K and more. In effect, and as I laid out in “Real Change for the Middle Class,” a benefit that was supposedly for the benefit of the middle class merely shifted the chips around for the top 20% of families—the top 2% pay more, the next 18% pay less—with little impact outside this narrow income range.

I presented those criticisms to the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance on October 26th, 2016 as it reviewed C-2 and, in part to address concerns that the proposed legislation did little for the middle class, the Committee amended the bill.

Not only is it rare for the Senate to amend House legislation, it’s encouraging to see the income inequality impacts of policy decisions being actively considered.

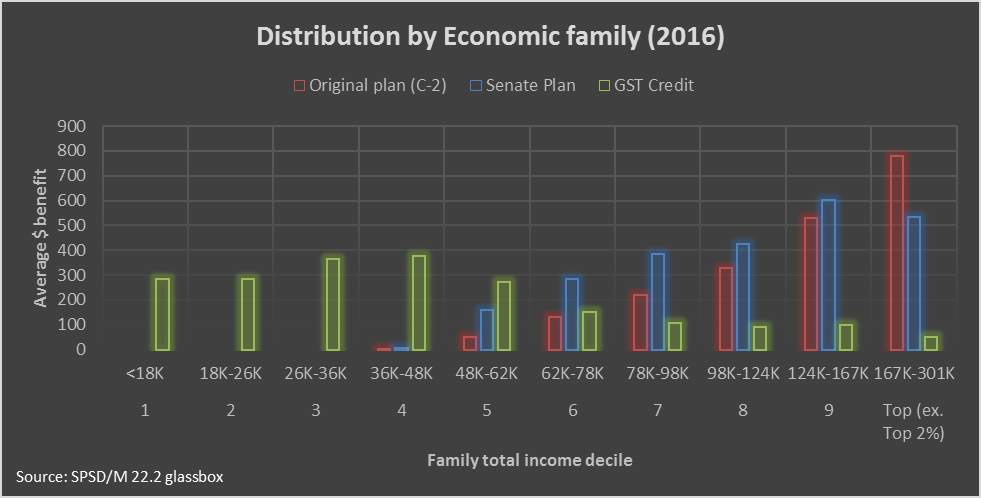

Here’s how the legislation (current and proposed) works: the graph below shows 10 equally-sized groups of Canadian families (deciles) sorted by pre-tax income. The red bars indicate the average annual amount that each decile receives from the original bracket trade plan. The top 2%, which is excluded from this graph (the new top bracket), will pay on average $9,200 more. However, the middle deciles 4, 5, and 6 (those making between $36K and $78K) only receive on average $2, $51, and $131 respectively from the shift. This is a pittance when compared to what the top decile (those making $167K to $301K) receives: $781 on average (again excluding the top 2% of families who will end up paying more).

The Senate amendment tries to make the bracket trade less regressive, but in so doing it creates two separate tax bracket systems, allowing the filer to pay whichever system calculates less tax. In short, it makes a mess of the system (and to spare you further details I’ll simply refer you to Tammy Schirle’s spreadsheet).

While this is clearly a non-ideal implementation (to say the least), the Senate Finance Committee is in a constitutional bind. It can only amend bills; it can’t rewrite them. Bill C-2 modifies the second tax bracket and, as a result, the Senate can only amend this modification to the second tax bracket, which likely is why it came up with this convoluted–if creative–approach.

Source: SPSDM 22.2 glass box with author’s modifications

As a result of the Committee’s amendments (in blue) the top decile of families no longer receives the greatest benefit; now it’s the 9th decile (those with incomes from $124K to $162K) at $603. The lower-middle class in decile 4 is really no better off under this amendment (receiving $6 instead of $2 on average a year). The 5th and 6th deciles are somewhat better off now, making $154 and $283 respectively, compared to the previous $51 and $131. And, as before, the bottom third of Canadian families gain nothing from either version of the legislation. Interestingly, the top 2% of families now actually pay more; on average $10,000 a year instead of $9,200 under the original bill.

But while the amendment makes the impact of C-2 less regressive, it could hardly be called progressive as most of the gains, outside of the top 2%, still go to the top.

It bears remembering what a progressive program could actually look like. The green bars on the chart are the average impact that could be realized by using the top bracket money to fund an improved GST credit. This would put much more money in the hands of the middle class without paying five to ten times as much to the richest Canadians, who don’t need it. Again, though, the Senate could not have chosen this approach as it could only amend what was in the bill, not rewrite it altogether.

If this amendment from Committee passes a full Senate vote, C-2 would be sent back to the House of Commons. Hopefully the House will realize that the overly-complicated nature of the amendment is a direct result of the constitutional constraints the Senate faces and accept the spirit, if not the letter, of the amendment.

The Senate Finance Committee’s amendment provides an opportunity for the House to rewrite the tax bracket shift with income inequality in mind. Perhaps the second time around, the House may design it so as not to concentrate gains at the top but rather to focus them on the middle class. This could be accomplished by improving the GST credit or (thinking outside the tax box) halving long-term care fees or eliminating undergraduate university tuition fees–each of which could be accomplished with the amount of money generated by the new top tax bracket.

David Macdonald is a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, and the coordinator of the Alternative Federal Budget. Follow him on Twitter @DavidMacCdn.