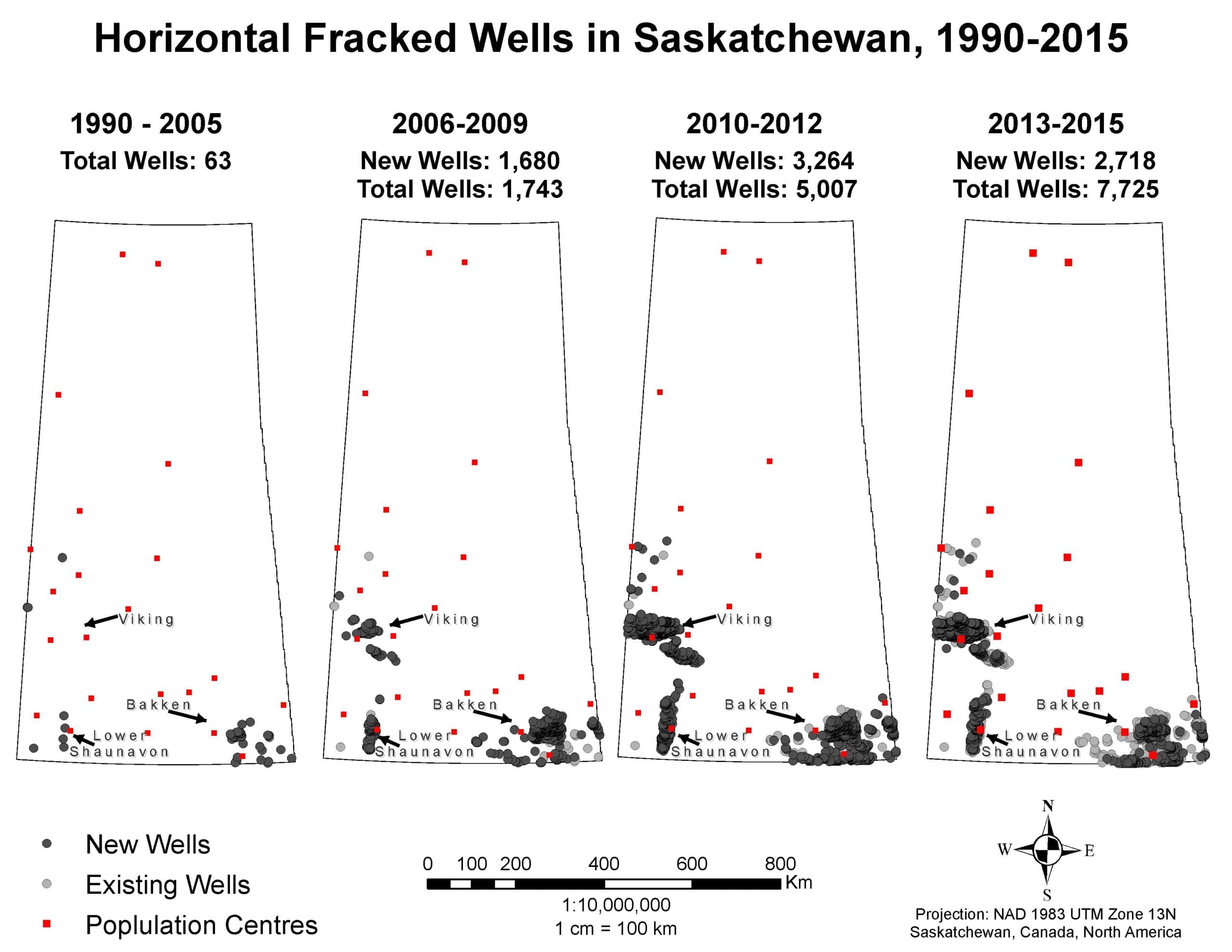

The combination of fracking and horizontal drilling ignited a shale oil boom in Saskatchewan, highlighted by exponential growth in the Bakken oil fields over the past decade. Wells drilled into the Bakken grew from just 75 in 2004 to nearly 3,000 by 2013. By 2015, there were over 7,500 horizontal fracked wells across the province. While the spread of fracking has incited intense public concern and a range of government regulation around the world (given the health and environmental risks of the extraction method), Saskatchewan government officials and industry representatives argue current regulations on fracking are “comprehensive” and “robust.” Is this accurate?

We attempt to provide an initial response to that question here. First we describe fracking, its risks and the typical regulatory responses to them. We then focus on the growth of the industry in Saskatchewan and its impacts, while also clarifying the government’s policy approach to fracking. We argue that Saskatchewan primarily applies existing oil and gas regulations to fracking with a few minimal revisions. At the same time, the government is weakening regulatory enforcement in the province by relying on industry self-regulation.

What the frack?

The use of fracking technology has spread rapidly across the United States and Canada since the 2000s when companies began to use multiple fracture treatments (multi-stage fracking) along horizontal drilling paths to access “tight” gas and oil reserves.

Fracking involves breaking up underground formations to release oil and gas trapped in small pockets of impermeable rock by pumping in a mix of water, chemicals and sand. The technology incited a boom in unconventional gas production in the U.S., but over the last decade it has also boosted tight oil production in Canada. The Bakken formation underlying Saskatchewan and Manitoba and bordering the U.S. is the largest producing tight oil play in the western region. In great part thanks to fracking technology, over a million barrels of crude oil a day are drawn from it.

Fracking is associated with a wide range of impacts: pollution or overuse of surface or groundwater; emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases; damage to wildlife habitat and rural communities due to extensive webs of infrastructure and traffic; threats to human health; interference with traditional subsistence and other sectors (tourism, ranching and agriculture); and earthquakes. Anti-fracking movements have grown across the globe since the late 1990s in response to these risks, with civil society groups demanding bans or stronger regulation of fracking. A notable example is the annual “Global Frackdown,” an international day of action against fracking that has been growing since it began in 2012.

In Canada and the U.S., fracking regulation is primarily left to provinces and states, though some local governments have also been very active in opposing fracking through implementing moratoria and bylaw revisions. Government responses to fracking vary widely, but typically they take one of three forms:

1) Moratoria or temporary bans: These are generally called to allow time to assess fracking’s impacts on the environment, as in New York, Nova Scotia, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

2) Permit, but regulate: Here governments opt to allow fracking after implementing more comprehensive regulatory changes to address the unique risks and impacts of extraction. Colorado is one example, as is Alberta, where Directive 083 specifies an “Unconventional Regulatory Framework,” and new requirements for monitoring and reporting seismic activity have been implemented.

3) Applying existing regulations to fracking: In this approach, any regulatory changes are slight, typically encouraging information disclosure about chemicals used in fracking.This is the case in Texas, which denies that fracking impacts groundwater and has not adjusted regulations. Yukon also took this approach when it ended a temporary moratorium to allow fracking in the Liard Basin, emphasizing that regulations are “robust, modern and designed to regulate all oil and gas activities.” Political scientist Dianne Rahm provocatively describes the Texas approach to fracking as “pretty much ‘the wild West’” of regulation. Although, in 2011, the state did legislate minimal disclosure of chemicals used in new wells, regulations are missing on water use, waste disposal and greenhouse gas emissions.

What explains these starkly different regulatory approaches? Studying Colorado and Texas, Charles Davis identifies several central factors: how much governments are dependent on oil and gas revenues, how supportive politicians and policy-makers are for oil and gas, and how much political influence the industry has in comparison to groups that might raise concerns about fracking, such as environmental organizations, municipalities and non-oil industries.

Davis describes how industry representatives and public officials have a shared interest in heavily oil-dependent states. They work together to expand oil and gas development while marginalizing groups expressing concern about fracking. Furthermore, as Barry Rabe and Christopher Borick observe, these governments are “reluctant to take any unilateral environmental policy steps that might threaten their economic well-being.”

Fracking Saskatchewan

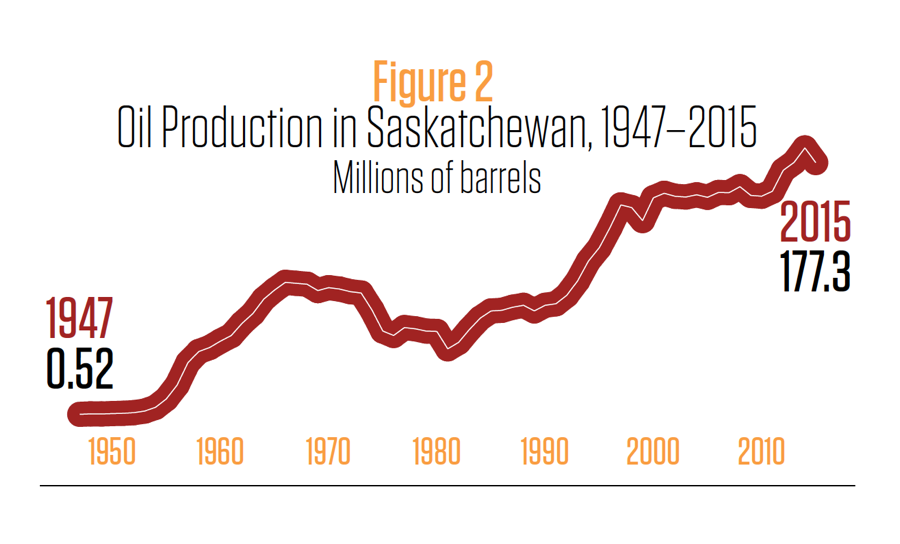

Saskatchewan has been producing oil on a commercial scale since the 1940s and has seen many spikes and slumps in production (see figure 2). Since the 1990s, however, production has reached new heights. Today, the government of Saskatchewan prides itself on being an “energy giant.” Indeed, the province is ranked sixth largest oil-producing jurisdiction on the North American continent, “behind only Texas, Alberta, North Dakota, California, and Alaska,” according to a 2015 government fact sheet.

Record-breaking oil production, drilling activity and petroleum rights sales over the last decade are due in part to the combination of horizontal drilling and multi-stage fracturing, which has boosted the production of “light, tight oil” in three main formations. The Bakken formation in southeast Saskatchewan is the most developed of these, producing 2.8 million barrels of light oil in December 2012, followed by the Viking and Lower Shaunavon formations.

Environmental consultants, landowners and environmental organizations interviewed for our research note many negative environmental impacts and significant risks from fracking. For example, multi-stage fracking uses extreme quantities of water (up to 750,000 gallons of fresh water per single well in Saskatchewan) that is lost from the hydrological cycle when it is disposed of deep underground. Moreover, the development of Saskatchewan’s Bakken oil has dramatically increased the venting and flaring of associated gas. In 2013, over 17% of the province’s GHG emissions came from the oil and gas sector’s “fugitive emissions” alone. Saskatchewan now has the highest GHG emissions per capita in the country.

Interviewees were also concerned about the surface impacts of fracking. The fragmentation of the province’s last vestiges of native prairie (which makes native species more vulnerable to encroachment from noxious weeds and imperils habitat) was highlighted by interviewees, along with the damage done to vegetative growth when highly saline produced water is spilled across the landscape. A spreadsheet available on the Ministry of the Economy website shows there have been more than 18,000 spills of salinated water, oil and natural gas in the province since 1990.

Despite new risks posed by the rapid growth in multi-stage fracking, the Saskatchewan Party government and policy-makers from the ministries of the economy and environment insist (without evidence) that fracking has not resulted in negative environmental impacts and has been done safely for 50 years. Yet in making this claim, government officials are equating the use of single frack jobs on horizontal wells (used over many decades in the province) with multi-stage fracking using horizontal wells, which introduces important risks, particularly relating to water. The government’s refusal to regulate this relatively new technique as a distinct practice is apparent in the Ministry of the Economy’s newly adopted (2012) oil and gas conservation regulations and by the Ministry of Environment’s de facto exemption of oil and gas wells from environmental assessment.

No new regulations

Oil and gas is regulated in Saskatchewan primarily by the Ministry of the Economy, established in 2012 with the stated aim of fostering economic growth. This super-ministry administers the oil and gas conservation regulations first adopted in 1985 and updated in 2012, more than five years after the oil industry began its intensive use of horizontal multi-stage fracking. Yet regulations pertaining specifically to fracking are conspicuous by their absence. In fact, there are only three regulations that specifically refer to fracturing in the 2012 update, and two of these were already part of the 1985 rules. The only new regulation pertaining to fracking prohibits the blending of high-vapour-pressure hydrocarbons with propping agents—usually a blend of ceramic, silica or resin-coated sand used to prop open fractures after a formation has been fracked.

Beyond enforceable regulations directly applicable to fracking, a regulatory guideline administered by the Ministry of the Economy prohibits the blowing of flowback fluids and sands into a pit or sump, or onto the surface of a lease. Instead, it recommends that fluids and frack sand be contained in a tank and disposed of in an approved disposal well. Companies need only notify the ministry of disposal and have 48 hours to do so. Unlike in British Columbia and Alberta, there is no requirement in Saskatchewan to disclose the contents of fracking fluids.

Other jurisdictions have responded to the increased risk of groundwater contamination posed by multi-stage fracking by strengthening requirements on the production casing used to line wells. In Saskatchewan, well casing requirements are uniform for fracked and non-fracked wells, and are minimal compared to standards applied in other jurisdictions. For example, while some U.S. states require cement bond logs and intermediate casing for fracked wells, neither are required in Saskatchewan. Furthermore, it is not necessary in the province to cement production casing to the surface, and adding casing strings (to protect against high pressure and high risk treatments) is at the discretion of the operator.

Finally, a recent directive on associated gas conservation is of relevance to fracking. Flaring is a critical issue arising from the rapid expansion of the technology. While it does not specifically reference fracking, Directive S-10 requires operators venting or flaring more than 900 cubic metres per day to implement conservation measures. However, the efficacy of this new directive is questionable since it can be circumscribed if operators can show that conserving gas is uneconomical or if venting and flaring are deemed temporary or non-routine.

Next to the Ministry of the Economy, the Ministry of Environment takes a clear secondary role in the regulation of oil and gas development in the province: it may review each oil and gas project, but it has granted industry a de facto exemption from environmental impact assessment.

One interviewee told us that since 1999 the Ministry of the Environment has provided letters to companies indicating that wells are not developments under the Environmental Assessment Act, thereby shielding them from undergoing an environmental impact assessment (EIA). According to data provided by the ministry, between 1995 and 2010 only two EIAs were completed for new oil and gas projects. Over the more recent 2006–2010 period, which saw an intense increase in oil well licensing, only one new oil and gas project underwent an assessment.

While individual oil wells may not pose significant environmental effects, the cumulative effect of thousands of wells drilled every year through technologies such as multi-stage fracking is certainly worthy of more thorough regulatory and environmental impact assessment by the province, and more public consultation.

Getting (further) out of the way

Not only has Saskatchewan neglected to implement new regulations to address the unique risks associated with the boom in fracking, the province is also actively undermining the ability of regulators to enforce even the existing rules.

Premier Wall has coupled a right-wing agenda of austerity in the public service with an ideological program of economic development characterized by “cutting red tape” and removing and reducing barriers to economic growth by “creat[ing] the best environment for business—and then get[ting] out of the way.” Indeed, the contraction of the public service has been a key priority for the Saskatchewan Party government, despite the province experiencing an economic boom from the mid-2000s to 2014. As noted recently by the Minister of Finance, the government has “embarked on a process to reduce the size and cost of government operations,” aiming to “reach a 15 per cent reduction in the size of the public service over four years primarily through attrition.”

In Saskatchewan, ensuring regulatory compliance is already challenging given that oil production happens across vast geographies in rural areas. But stagnating staff numbers and booming industry activity strain the regulatory system even further. A series of CBC news reports in 2015 showed widespread and chronic problems with wells across the province leaking gas containing hydrogen sulphide (which can cause serious harm or death to animals and humans) at concentrations that well exceeded the regulatory maximum. Referring to regulatory enforcement in the province, the assistant deputy minister of the Ministry of the Economy’s petroleum and natural gas division admitted, “there’s [sic] been sites that have not received the attention they should,” and noted the ministry does not have “enough boots on the ground to get this work done” given the ongoing oil boom.

Workers at the four regional petroleum development offices responsible for regulatory compliance in the province told us that field staff are finding it increasingly difficult to proactively audit and inspect the industry. Rather, their jobs mostly involve reacting to incidents such as spills, and responding to complaints from landowners and the general public. In one field office an interviewee reported that three field staff are responsible for enforcing the regulations—from the initial exploration through drilling, production and abandonment phases—on roughly 20,000 wells. Another interviewee highlighted that the number of staff in the office has remained the same since the 1980s while the number of wells in the region has increased dramatically, leaving less time for random field inspection of wells.

Field office staff admit they do not have enough time to enforce all the regulations, so they prioritize only certain issues and supplement the enforcement of “minor infractions” by employing summer students. Moreover, to avoid new hiring, site reclamation enforcement is contracted out to private consultants whose work is monitored by regional offices.

The Wall government is further diminishing regulatory oversight through processes of industry self-service and what it calls “regulation by declaration.” Ed Danscok, Saskatchewan’s senior strategic lead for oil and gas development, claimed this process allows companies to self-declare that they meet regulatory requirements, which reduces the role (and therefore workload) of the ministry to conducting random audits rather than overseeing each application and project. All routine applications for drilling, including routine horizontal multi-stage fracking, now receive instantaneous approval through an online “self-service” submission tool that grants approval from all three ministries (environment, economy and agriculture) involved in the regulation of oil and gas.

In other words, the Saskatchewan government is actively retreating from regulating oil and gas: industry will self-declare compliance and government oversight will be diminished to random audits. According to a regulator interviewed for this research, Saskatchewan’s “regulation by declaration” approach is novel in Canada, with jurisdictions like Alberta keenly interested in implementing it should it be deemed a success.

Why is Saskatchewan a regulatory laggard?

Given Davis’s understanding of the variance in fracking regulation, Saskatchewan’s minimalist approach makes sense. The province emphasizes that oil and gas is “one of Saskatchewan’s leading industries.” Oil royalties accounted for $1.5 billion of government revenue in 2013-14, with an additional $106 million from the sale of provincial lands to oil companies, which combined represents close to 14% of the province’s total revenue. In addition, the oil and gas sector provided approximately 33,000 person-years of employment in 2015. This is no small contribution in a province that has bled agricultural jobs in rural communities over the last two decades.

At the same time, the interests of the oil industry are easily heard by politicians and policy-makers. As noted in a recent CCPA-Saskatchewan study, oil, gas and uranium companies make significant contributions to both the Saskatchewan Party and the NDP (28% and 22% of top corporate contributions respectively between 2008 and 2010). Oil companies are top funders of the Saskatchewan Party: in the 2011 election year, Crescent Point Resources, the largest tight-oil extraction company, contributed the third largest corporate contribution to the party.

Industry representatives are also actively involved in oil and gas policy-making as part of the Saskatchewan Petroleum Industry/Government Environment Committee (SPIGEC). Through SPIGEC, industry associations work alongside departmental ministers to develop regulatory guidelines for the oil and gas sector, including the 2012 minor reforms to fracking rules.

Petroleum industry executives and managers are obviously pleased with the regulatory environment they have helped to create in Saskatchewan: as documented in the Fraser Institute’s 2015 Global Petroleum Survey, “Saskatchewan is once again the top-ranked Canadian province on the ‘policy perception index.’” Saskatchewan is also the top-ranked Canadian province in terms of environmental regulations and considered the “most attractive” Canadian province for petroleum exploration and development.”

Elected officials from both major parties seem happy to conserve this “favourable” regulatory environment by supporting fracking and downplaying its risks. This was plainly demonstrated in the bipartisan support of the Saskatchewan Party’s 2013 motion in the legislature that affirmed the assembly’s endorsement for the continued use of hydraulic fracturing in Saskatchewan’s energy sector.

While the province has a long history of environmental social movements opposing the nuclear industry, to date there has been limited organized opposition to the oil and gas industry or fracking specifically. Nor have the concerns of rural landowners coalesced into the kind of anti-fracking lobby notable in Colorado and other U.S. states.

Rural landowners interviewed for our research expressed severe grievances with, yet dependence on, industry. They receive income from surface leases (roughly $1,500 to $3,000 per well per year) and from selling access to surface water, disposing of drilling mud and/or trucking or removing snow for the industry. These off-farm sources of income are important given declining agricultural economies; landowners do not want to jeopardize the jobs and livelihoods of people in their families and communities by speaking against the oil industry.

Organized public opposition to fracking has developed in other provinces with important oil and gas sectors such as B.C., Alberta, and Newfoundland and Labrador. While a similar kind of mobilization is not yet apparent in Saskatchewan, opposition to fracking is growing in Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities alike. This may pick up in response to new evidence of the negative impacts of fracking in the province being documented in scientific research or revealed through environmental and public health incidents that are clearly linked to fracking.

Canada’s Texas?

Public opposition to fracking has spread to wherever the technique is used across the world. Governments in Canada and the U.S. have generally responded by either banning the practice, regulating it or effectively ignoring it. Saskatchewan has taken the latter path, in all likelihood due to the province’s economic dependence on oil, the political influence of industry, legislative and bureaucratic support for the sector from all major political parties and the limited opposition to fracking from environmental organizations and landowners.

In contrast to jurisdictions that have paused or stopped fracking to study the environmental and safety impacts, Saskatchewan is allowing it to take place under current regulations developed for conventional oil and gas activities. The province has not even implemented requirements for companies to publicly disclose the chemicals they use to frack—a minimal request in jurisdictions, including Texas, taking the most hands-off approach to regulation.

Contrary to the claims of public officials and industry representatives, the province’s fracking regulations are hardly “robust” or “comprehensive.” In fact, the Wall government is “streamlining” the licensing, regulation and monitoring processes for all oil development, including fracking, and moving toward a system of industry self-service and self-regulation. In this way, Saskatchewan presents an even more remarkable example of “wild West’” fracking regulation than Rahm found in Texas.

Angela Carter is Assistant Professor in the department of political science at the University of Waterloo. She researches comparative environmental policy regimes surrounding oil developments primarily in Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Saskatchewan.

Emily Eaton is Associate Professor in the department of geography and environmental studies at the University of Regina. For a photographic and accessible overview of oil in the province, please see her newly released book (with photographer Valerie Zink), Fault Lines: Life and Landscape in Saskatchewan’s Oil Economy (University of Manitoba Press).

This article was published in the September/October 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.