When the RCMP’s armoured vehicles entered into the unsurrendered, unceded territory of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation on February 6, 2020, one hereditary chief described them as an invading army.1 The officers had dressed for the part, arriving in tactical gear and fully armed.

This style of arrival and dress has become increasingly common for police forces across Canada post-9/11. So how did we get here and why do Indigenous communities face disproportionate force when encountering militarized police forces? In order to get those answers we have to first revisit the history of policing in Canada.

The Northwest Mounted Police and colonial inroads

The history of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) begins with an earlier iteration of the force during the settlement period of Canada’s colonization. The Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) was established in 1873 as a pan-Canadian police force.2 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (the MMIWG Commission’s report) notes that the NWMP combined military, police and judicial functions. As European settlers began to populate the prairies, historian Sarah Carter explains that Indigenous people came to be seen as a “distinct threat to the property and lives of [these] white settlers.”3 This led the NWMP to enforce an illegal pass system requiring all Indigenous people to obtain a pass before leaving the reserve. However, many people needed to access local towns for work and to secure an income. The penalty for any First Nations person found in a local town without a valid pass could be arrested. First Nations women found without a pass risked being brought to the NWMP barracks where they risked “physical harm and violence.”4

The dehumanizing of Indigenous women extended beyond the pass system. First Nations women were hypersexualized and had their mothering skills called into question by members of the settler community. This atmosphere allowed flagrant police misconduct to be ignored, despite it being flagged the the Lieutenant-Governor for the Northwest Territories in 1878, in a letter to the NWMP Commissioner James Macleod. In 1880, Manitoba Member of Parliament Joseph Royal raised the issue of the NWMP’s “disgraceful immorality” and their human trafficking of Indigenous women. The issues were once again raised by Liberal MP Malcolm Cameron in 1886. But, in an all-too-familiar scenario, the NWMP was responsible for investigating itself and, as such, allegations of misconduct were commonly dismissed.5

“Métis scholar and activist Howard Adams has explained: [Indigenous people] suffered brutality under the Mounties, who frequently paraded through native settlements in order to intimidate the people and remind the natives they had to “stay in their place.” … The Mounties were not ambassadors of goodwill or uniformed men sent to protect [Indigenous people]; they were the colonizer’s occupational forces and hence the oppressors of [First Nations] and Métis.”6

As Sherene Razack reflects on in her book, Dying from Improvement, “From its inception as a colonial police force, the Northwest Mounted Police, which would become the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, assisted in securing the territory, ultimately transforming its largely military function into a domestic policing of the settler’s town, a town surrounded by reserves. Colonial policing…persists into the present. Keeping order in public space still largely means mostly non-Indigenous police controlling the movements of Indigenous people in city space.”7

On the opposite side of the disproportionate force equation is what the MMIWG Commission describes as a “long-standing indifference” from Canadian police forces when Indigenous people are victims of violent crimes.8 This indifference extends from micro, or anecdotal, incidents to macro level experiences. In Volume 1b of their report, the Commission notes the RCMP’s profound reluctance to comply with requests to provide information. “The degree to which the RCMP, represented by the Department of Justice, resisted disclosure of the files sought by the [Forensic Document Review Project (FDRP)] created a challenge to its ability to obtain and review the necessary documents. Many of the files received contained redactions that rendered some documents unintelligible. This affected the analysis. This is particularly significant because the RCMP is the national police force responsible for policing approximately 40% of the Indigenous population and 39% of unsolved cases reviewed by FDRP.”9

This Idle No More Movement is like bacteria, it has grown a life of its own all across this nation. Email from RCMP Corporal Wayne Russett.

“This Idle No More Movement is like bacteria, it has grown a life of its own all across this nation.” Email from RCMP Corporal Wayne Russett

Where we are now

When we consider how disproportionate force is playing out in a post-9/11 contest, we have to consider two forces at play. The first is a deep-seated, systemic discrimination against FNIM people. The second is the militarization of police forces across Canada.

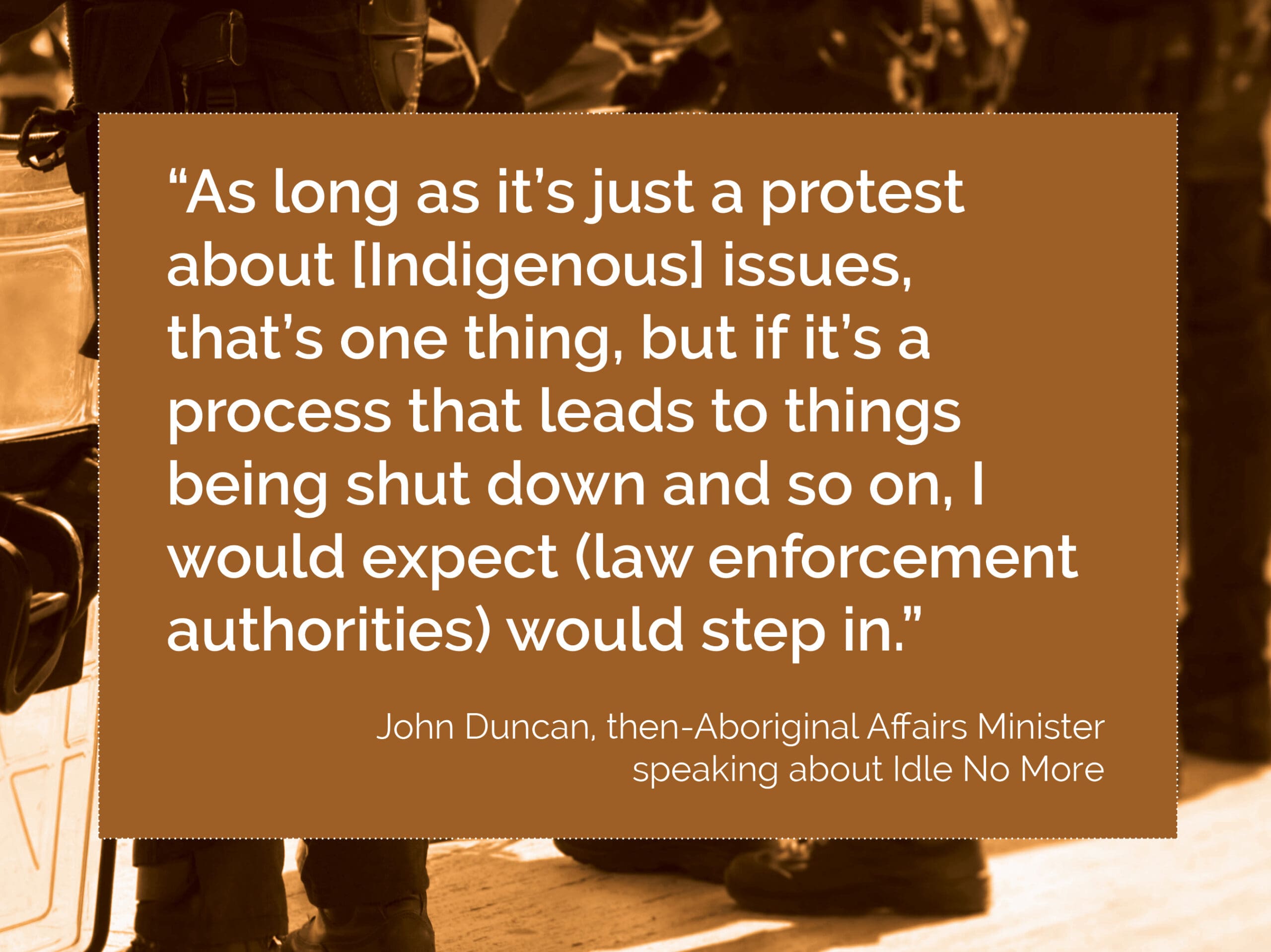

On the protest front, Indigenous land defenders face disproportionate force when asserting their sovereignty. During the Idle No More protests, then-Aboriginal Affairs Minister John Duncan stated his position on the Indigenous communities’ right to protest as fine, provided as it maintained a limited scope with limited impact. As long as it’s just a protest about [Indigenous] issues, that’s one thing, but if it’s a process that leads to things being shut down and so on, I would expect (law enforcement authorities) would step in.10

This Idle No More Movement is like bacteria, it has grown a life of its own all across this nation. It may be advisable for all to have contingency plans in place, as this is one issue that is not going to go away…. There is a high probability that we could see flash mobs, round dances and blockades become much less compliant to laws in an attempt to get their point across. The escalation of violence is ever near.” Email from RCMP Corporal Wayne Russett, the Aboriginal liaison for the national capital region, to Inspector Mike LeSage, the acting director general for National Aboriginal Policing.

Reviewing the security documents produced during the surveillance of Idle No More, researchers found a two-pronged approach to framing Indigenous movements: both as criminal threats with the potential to disrupt Canada’s economic status quo and as “extremists,” a powerful label in the post-9/11 age of counterterrorism.11 This frame of “extremism” is critically important for “blurring the boundaries between activism, protests and terrorism.”12 While extremely potent in the post-9/11 context, this frame is not new and has been used against Indigenous resistance movements for decades.

Given the continued use of excessive force against land and water defenders, this is likely what first comes to mind when thinking about the problem of disproportionate force—the heavy handed treatment of Indigenous elders and supporters at blockades such as those found at Fairy Creek and Wet’suwet’en. This behaviour was decried by B.C. Supreme Court Justice Douglas Thompson in his ruling against Teal Cedar’s injunction extension request in October 2021.13

“Some of the videos do show disquieting lapses in reasonable crowd control. One series of images shows a police officer repeatedly pulling COVID masks off protesters’ faces while pepper spray was about to be employed… I considered the infringements of civil liberties to be unjustified, substantial, and serious. It goes without saying that unlawful measures imposed by those given authority to enforce the Court’s order does no credit to the rule of law or the Court’s reputation, especially when those measures trench on civil liberties in a substantial way.”14

However, the use of excessive force against Indigenous people does not end at the barricade.

In their 2016 Submission to the Government of Canada on Police Abuse of Indigenous Women in Saskatchewan and Failures to Protect Women from Violence, Human Rights Watch cited excessive force as one of the most common types of police abuse experienced by Indigenous women in the province. In addition to recording experiences of excessive use of force among interview participants, “Human Rights Watch documented at least six incidents in which the relevant municipal police service or the RCMP reportedly used excessive force against Indigenous women in Saskatchewan.”15

That same year, in an investigation for Maclean’s, Nancy Macdonald filed eight Freedom of Information requests with Western Canadian police agencies to obtain race-disaggregated data in order to ascertain the correlations between race and discretionary police stops. None of the agencies contacted provided the information requested, with the Edmonton Police Service estimating that providing the data would cost Maclean’s $7,693. In Saskatchewan, Macdonald learned, “municipal police are exempted from Freedom of Information laws, and the Regina Police Service instructed their legal counsel to refuse the request.”16

What Macdonald was able to learn in a separate survey of over 850 students in Saskatoon, Regina and Winnipeg, conducted in partnership with Discourse Media, was that “Indigenous students are more likely to be stopped by police than non-Indigenous students, and staying away from illegal activity does not shield them from unwanted police attention.”17

9/11 and the militarization of police forces

The model of policing that most readers are likely familiar with, and that is most commonly presented to Canadians, is a “community policing” model. This style of policing centres on building relationships with communities and focuses on crime prevention. As researchers Brendan Roziere and Kevin Walby found in their FOI-fuelled examination of Canada’s police services, the use of militarization by police forces is on the rise. Militarization is antithetical to the community policing model and brings with it its own military policing mentality, which sees the police as outside of the communities, acting as anonymous enforcers. Because they do not belong to the community, they are not accountable to the community and they are inherently suspicious of its members.

Militarized policing is not new. “The Los Angeles Police Department first introduced the special weapons and tactics (SWAT) concept in 1967 based on United States Marine Corps training and Vietnam war veterans recruited into the police force after the Watts riots.”18 The RCMP’s original tactical unit was established in the mid-1970s for the United Nations Habitat conference in Vancouver and the Montreal Olympics. “The focus was predominantly major event security, hostage-taking, and counter-terrorism.”19

What is new is the spread of militarization to municipal police forces across Canada. It is difficult to get a complete picture of the extent of militarization of Canada’s police forces. What has been documented is some of the acquisition efforts related to armoured vehicles. The CBC reported in 2014 that in Ontario, Windsor, Toronto, London, Peel, Hamilton, Durham, Sault Ste. Marie, and Ottawa had former military vehicles.20 Other Canadian cities with armoured vehicles include Vancouver, Victoria, Surrey, Abbotsford, Calgary,21 Edmonton,22 Regina, Saskatoon,23 Winnipeg, Brandon,24 Halton, Peterborough, Montreal,25 New Glasgow, St. John’s26 and Fredericton.27 Between 2007 and 2014, the Department of National Defence donated five six-wheeled armoured vehicles to police agencies in Edmonton, New Glasgow, Windsor, and two to the B.C. RCMP.28 When purchased new, each of these vehicles, cost between $343,0029 and $500,000.30

While police paramilitary units (PPU) and SWAT teams prior to 9/11 deployed an average of 60 times per year (1980-1997), Roziere and Walby found that, as of 2017, the average number of yearly deployments was 1,300 per agency representing a 2,100% increase in 37 years.31 Militarized police practices are more likely to be used against marginalized communities including Indigenous communities.32 The use of force by PPUs has been shown to lead to more frequent use of lethal force against civilians.33 The city that had the highest rate of deployment of their PPU in Roziere and Walby’s study was Winnipeg, the Canadian city that also has the largest FNIM population.34

With regards to increased militarization of the RCMP, understanding the extent of this is difficult. “Available information about the RCMP is remarkably hard to come by because the Canadian police force is extremely protective of its reputation and brand. Persons inside and outside the RCMP are even unwilling to admit the existence of militarization.” What we do know is the RCMP’s two year series of raids on the Wet’suwet’en First Nation who are blocking Coastal Gaslink’s access to their land. In the first three months of 2019 alone, the RCMP’s operation against the Wet’suwet’en cost $1,464,691 CAD. Now feels like an important time to hearken back to the RCMP’s defense in not providing the MMIWG Commission with the documents they requested, saying that they didn’t have the staffing available to fulfill the request.

As Canada doubles down on its identity as a petrostate, the role of militarized police forces and the use of disproportionate force become ever more important to protecting the interests of the state. Writing about the use of excessive force against the Idle No More movement, Crosby and Monaghan introduce the logic of elimination as a key concept for understanding the continual use of disproportionate violence by state actors. “As Wolfe (2006) notes, the genocidal logic of settler colonialism is a structure, not an event. Though we can highlight particular events within our understanding of settler governmentality, it is the rationalities of colonialism that make the everyday practices of Canadian governance seem “normal.”35

Framing colonialism as something of the past… de-historicizes existing colonial relationships and displaces an understanding of the links between incarceration, sovereignty, and the state. – Vicki Chartrand.

“Framing colonialism as something of the past… de-historicizes existing colonial relationships and displaces an understanding of the links between incarceration, sovereignty, and the state.” – Vicki Chartrand

Where can we go from here?

Researcher Vicki Chartrand argues that one critical step Canadians need to take is to stop talking about colonization as though it is something that happened in the past. Framing colonialism as something of the past [e.g. colonization’s legacy], however, de-historicizes existing colonial relationships and displaces an understanding of the links between incarceration, sovereignty, and the state. Indigenous struggles and experiences are thus symptomized as an unfortunate but inevitable consequence, while the structural and systemic manners in which Indigenous people continue to be colonized are rarely explored.36

From the MMIWG Commission’s Recommendations: The idea of access to justice is broader than the simple administration of the courts, or the conduct of police, though… A human rights-based approach to justice therefore involves understanding that justice is a broader concept than just administration. Applying human rights standards to justice-related issues involves:

- focusing on the immediate, as well as underlying, causes of the problem;

- identifying “claim holders” as those most vulnerable, or, as the National Inquiry heard, who are targeted;

- identifying “duty bearers,” those who are responsible for addressing issues or problems, including government institutions, groups, community leadership, and others; and

- assessing and analyzing the ability of claim holders to access their rights, as well as duty bearers to meet their own duties and obligations with relation to those rights–and putting in place systems to allow each to do so.37

Rights guaranteed by UNDRIP and the UN Human Rights

UNDRIP Article 1 Indigenous peoples have the right to the full enjoyment, as a collective or as individuals, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms as recognized in the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and international human rights law

UDHR Article 3. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

UDHR Article 5. No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

UDHR Article 20 (1) Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

UNDRIP Article 2 Indigenous peoples and individuals are free and equal to all other peoples and individuals and have the right to be free from any kind of discrimination, in the exercise of their rights, in particular that based on their indigenous origin or identity.

UNDRIP Article 3 Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

UNDRIP Article 10 Indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories. No relocation shall take place without the free, prior and informed consent of the indigenous peoples concerned and after agreement on just and fair compensation and, where possible, with the option of return.

UNDRIP Article 26 1. Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired. 2. Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired. 3. States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned.

UNDRIP Article 29. 1. Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programmes for indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without discrimination.

UNDRIP Article 30. 1. Military activities shall not take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples, unless justified by a relevant public interest or otherwise freely agreed with or requested by the indigenous peoples concerned.38

Notes

1 Madsen, C. (2020). Green is the New Black: The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Militarisation of Policing in Canada. Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies, 3(1), 114–131.

2 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a.

3 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a, page 253.

4 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a, page 255.

5 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a.

6 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a, page 258.

7 Page 14, Razack, S. (2015). Dying from Improvement: Inquests and Inquiries Into Indigenous Deaths in Custody. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

8 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a, page 629.

9 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1b, page 242.

10 Quoted page 48 in Crosby, A. and Monaghan, J. (2016). Settler Colonialism and the Policing of Idle No More. Studies in Social Justice. 43(2). 37-57.

11 Crosby, A. and Monaghan, J. (2016). Settler Colonialism and the Policing of Idle No More. Studies in Social Justice. 43(2). 37-57.

12 Page 50. Crosby, A. and Monaghan, J. (2016). Settler Colonialism and the Policing of Idle No More. Studies in Social Justice. 43(2). 37-57.

13 https://www.bccourts.ca/jdb-tx…

14 https://www.bccourts.ca/jdb-tx…

15 Page 10, https://www.hrw.org/sites/defa…

16 macleans.ca/news/canada/canadas-prisons-are-the-new-residential-schools/

17 Retrieved from a cached version of the Discourse Media website on the Wayback Machine, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20…

18 Madsen, C. (2020). Green is the New Black: The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Militarisation of Policing in Canada. Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies, 3(1), 114–131. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31374/sjms.42

19 Madsen, C. (2020). Green is the New Black: The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Militarisation of Policing in Canada. Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies, 3(1), 114–131. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31374/sjms.42

20 https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada…

21 https://www.thestar.com/halifa…

22 https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada…

23 https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/ca…

24 https://www.macleans.ca/news/c…

25 https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/ca…

26 https://www.macleans.ca/news/c…

27 https://www.thestar.com/halifa…

28 https://nationalpost.com/news/…

29 https://www.winnipegfreepress….

30 https://www.thestar.com/halifa…

31 Roziere, B., Walby, K. The Expansion and Normalization of Police Militarization in Canada. Crit Crim 26, 29–48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612…

32 Gamal, F. (2016). The Racial Politics of Protection: A Critical Race Examination of Police Militarization. California Law Review, 104(4), 979–1008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24758742, Roziere, B., Walby, K. The Expansion and Normalization of Police Militarization in Canada. Crit Crim 26, 29–48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612…

33 Delehanty, C., Mewhirter, J., Welch, R., & Wilks, J. (2017). Militarization and police violence: The case of the 1033 program. Research & Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017712885, Roziere, B., Walby, K. The Expansion and Normalization of Police Militarization in Canada. Crit Crim 26, 29–48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612…

34 Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016.

35 Crosby, A. & Monaghan, J. (2016). Settler Colonialism and the Policing of Idle No More. Studies in Social Justice. 43(2). 37-57.

36 Chartrand, V. (2019). Unsettled Times: Indigenous Incarceration and the Links between Colonialism and the Penitentiary in Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 61(3) 67-89. DOI:10.3138/cjccj.2018-0029

37 Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Volume 1a, page 623-624.

38 [the United Nations’ website is currently experiencing difficulty with the UNDRIP document. This is where it was previously available.] https://www.un.org/development…

Further Reading

Kappeler, V.E. & Kraska, P.B. (2013). Normalising police militarisation, living in denial. Policing and Society. https://www.tandfonline.com/do…

Marikan, B. (2016). Creeping militarization : Why are Canada’s police officers looking increasingly like soldiers? The Ploughshares Monitor. https://ploughshares.ca/pl_pub…

Monaghan, J. (2016). Mounties in the Frontier: Circulations, Anxieties, and Myths of Settler Colonial Policing in Canada. Journal of Canadian Studies. https://www.utpjournals.press/…

Nettelbeck, A. & Smandych, R. (2010). Policing Indigenous Peoples on Two Colonial Frontiers: Australia’s Mounted Police and Canada’s North-West Mounted Police. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. http://drc.usask.ca/projects/l…

Simpson, A. (2016). Whither settler colonialism? Settler Colonial Studies. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2201…

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Katie Sheedy who provided illustrations for the print version of this article. Thank you also to the community on Twitter who crowdsourced information about which municipalities in Canada had purchased or been gifted APCs.