Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

The Ontario PC government has announced the first cues about its plans for social assistance reform. Given that the previous PC government axed social assistance rates by 21.6%, there’s been widespread fear that rate cuts from the Ford government were on the horizon.

But last week’s announcement included no immediate rate cuts. It appears that the current government’s plan is more sophisticated but equally perverse to that of the previous Harris government: it aims to push social assistance recipients with disabilities into a cheaper program with fewer supports. If this happens, a considerable portion of the people who will be affected are 55 years of age and older.

While the Income Security Advocacy Centre’s (ISAC) analysis explains the potential implications of the announced changes, and Nick Saul’s op-ed offers a trenchant rebuttal of the government’s rhetoric, this blog provides data that contextualizes the likely motivation and potential impact of the forthcoming reform.

The context in numbers

Ontario’s social assistance system comprises two programs: Ontario Works (OW), which provides financial and employment support to people not in receipt of employment insurance; and the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP), which provides financial and employment support to people with disabilities.

In July 2018, OW had 245,322 cases with 451,827 total beneficiaries (including spouses and dependant children). Caseload sizes have oscillated up and down by 4.5% in the past three years, with a 3% decline in the past 12 months.¹ The OW maximum monthly benefit is $733 for a single person and $1,484 for a couple with two children.²

In July 2018, ODSP had 368,614 cases with and 508,459 total beneficiaries. Caseload size has been on the rise, with an accumulated 10% increase in the past three years.³ The ODSP maximum monthly benefit is $1,169 for a single person and $2,121 for a couple with two children.⁴

The ODSP program cost ($5.6 billion) is almost twice as much as the OW’s program cost ($3 billion).⁵

In its pursuit of an austerity agenda, the PC government already cut by half a scheduled 3% rate increase. Next, it seems the government plans to push ODSP clients onto OW.

New disability definition

The Reforming Social Assistance Backgrounder states the Ontario government is working on a new definition of disability—which will more closely align with federal government guidelines. A likely definition is the one used to determine eligibility for Canadian Pension Plan (CPP) disability benefits.

We estimate that 149,000 Ontarians received the CPP disability benefit in 2016, whereas 795,000 received provincial social assistance income.⁶ Ontario government data shows that only 9% of ODSP recipients and 0.1% of OW recipients received both social assistance and CPP benefits in the same year.⁷

The small overlap between CCP disability and ODSP is not due only to different disability definitions.

Since CPP is a contributory program, eligibility for disability benefits depends on both contributions and the definition of disability. The contribution requirement likely bars many ODSP recipients from receiving the federal benefit. Moreover, CPP disability benefits are deducted dollar-for-dollar from ODSP benefits, which is a disincentive for applying to both programs.

Notwithstanding these caveats, these figures suggest that alignment with federal guidelines means less people will qualify for ODSP.

“Moving People to Employment”

The backgrounder document states that “only 1% of people on Ontario Works leave the program for a job in any given month” and that the “number of people receiving [ODSP] support has been growing by 3.5% each year, significantly outpacing Ontario’s population growth.” The proposed solution to “make social assistance sustainable” is largely focused on “moving people to employment.”

Between 2012 and 2016, the number of Ontarians receiving social assistance income grew by an annual average of 3.8%. As Chart 1 shows, the average annual growth for recipients between 16 and 24 years of age is negative (-0.8%); and the average growth for the 25 to 54 years age group (+0.4%) is well below the overall average. Growth is above the average only for the age groups between 55 and 64 (+13.6%) and 65 and over (+15.1%).⁸

Chart 1| Average Annual Growth of Social Assistance Recipients by Age Group, 2012-2016

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table: 11-10-0239-01, and author’s calculations.

As a result, the size of older age groups as a share of social assistance caseloads is rapidly increasing. In the same five-year period, the share of social assistance recipients between 25 and 54 years of age dropped from 65% to 55%, whereas the share of individuals 55 to 64 years of age went up from 17% to 24%, and the share of the group 65 years and over increased from 9% to 13%.

While older age is not in an impediment to work, adults approaching retirement age face considerable employment barriers. Ontario Works requires recipients to continually look for work or undertake work-related training to be eligible for support. Older adults with disabilities no longer eligible for ODSP may not be able live up to these requirements; there is a risk they may lose all income supports.

Low-Income tax credit

In her announcement of the social assistance changes, Minister Lisa MacLeod touted the new low-income tax credit as an aid to individuals and families on social assistance. In an earlier blog post, we compared the impact of the low-income tax break and the axed minimum wage increase.

Here, it is important to note that only 17% of social assistance recipients will have provincial taxes payable in 2018. The tax rate applicable to their income bracket is 5.05%, with many individuals paying a lower effective tax rate due to other tax credits and deductions.

For social assistance recipients, real taxation comes in the form of benefit clawbacks due to employment income.

Earning exemptions and clawback rates

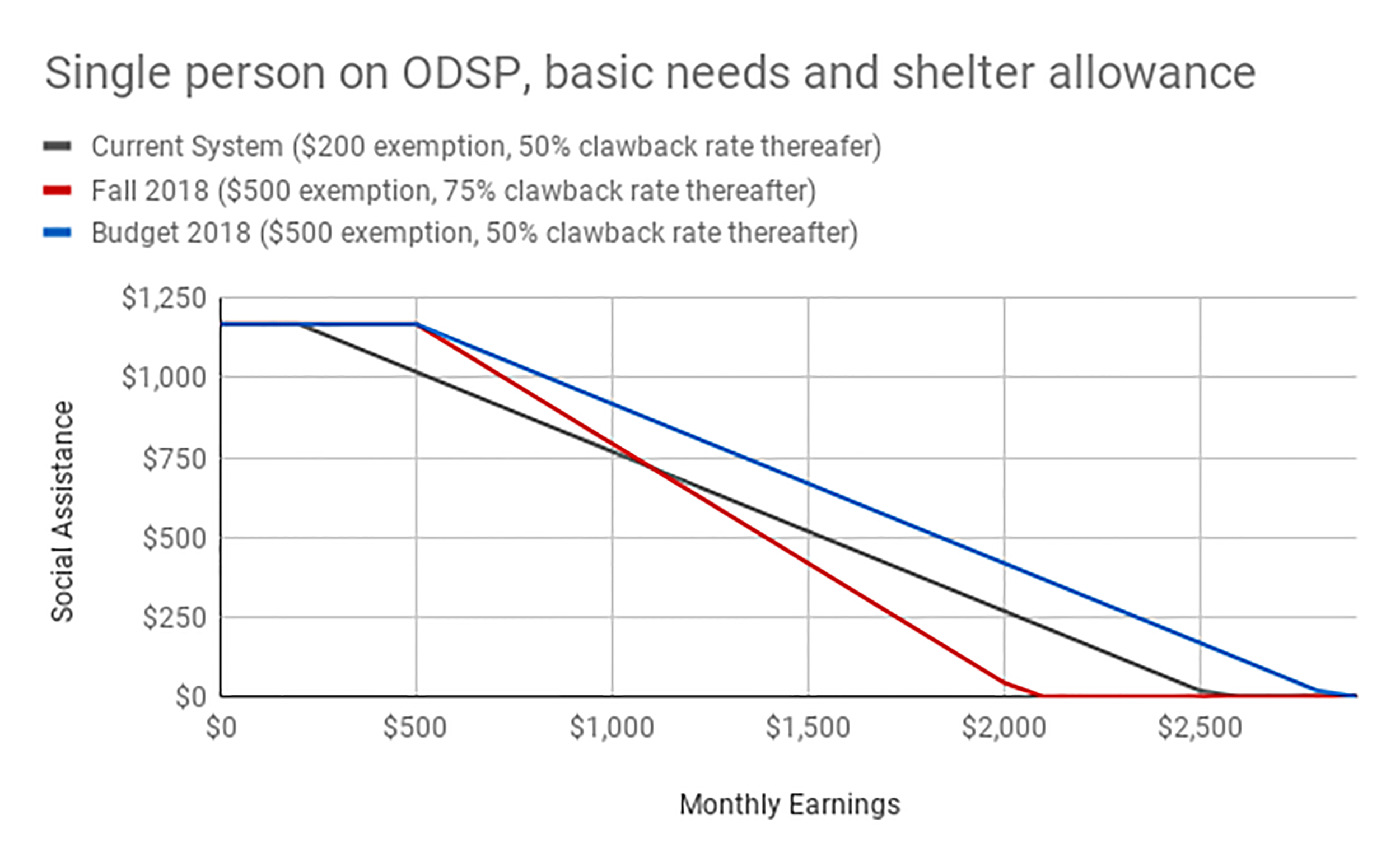

The Ontario government is increasing the employment earnings exemptions for both programs. From $200 to $300 a month for OW and from $200 monthly to $6,000 annually for ODSP. This measure would have been a positive change, if the government had not raised clawback rates on earnings above these amounts from 50% to 75%. As Graph 2 clearly shows, social assistance recipients will be taxed more on their employment incomes as a result of these changes.

Chart 2| Earnings Exceptions and Clawback Rates Compared

Source: Maytree, Hannah Aldridge’s calculations and graph; forthcoming publication will be available on https://maytree.com/publications/

Pressed by a reporter on whether the new disability definition will limit access to ODSP, Minister Lisa MacLeod said, “everybody who is on ODSP today will be grandfathered, on a go forward basis, they may end up on Ontario Works, and they will be provided with those wrap around supports at the local level.”

The figures discussed above and this remark by Minister MacLeod suggest the PC government social assistance reform will limit access to ODSP and push the responsibility for Ontarians’ health and wellbeing onto municipal governments—tasked with the delivery of Ontario Works and other crucial supports—and community organizations that pick up the tab whenever governments fail.

¹ Government of Ontario, Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, Social Assistance in Ontario: Reports – Ontario Works. 2016-2018 figures https://mcss.gov.on.ca/documents/en/mcss/social/reports/OW_EN_2018-07.pdf, and 2014-2016 figures https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/documents/en/mcss/social/reports/OW_EN_2016-11.pdf.

², ⁴ Income Security Advocacy Centre (ISAC), OW and ODSP Rates and the OCB 2018, Available at http://incomesecurity.org/publications/social-assistance-rates/OW-and-ODSP-rates-and-OCB-as-of-Sept-2018-ENGLISH.docx.

³ Government of Ontario, Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, Social Assistance in Ontario: Reports – Ontario Disability Support Program. 2016-2018 figures https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/documents/en/mcss/social/reports/ODSP_EN_2018-07.pdf; and 2015-2017 figures https://mcss.gov.on.ca/documents/en/mcss/social/reports/ODSP_EN_2017-06.pdf

⁵ Government of Ontario, Expenditures Estimates for the Ministry of Community and Social Services (2018-19). Available at, https://www.ontario.ca/page/expenditure-estimates-ministry-community-and-social-services-2018-19 – section-1.

⁶ This analysis is based on Statistics Canada’s Social Policy Simulation Database and Model (SPSD-M). The assumptions and calculations underlying the simulation results were prepared by Ricardo Tranjan and the responsibility for the use and interpretation of these data is entirely that of the author.

⁷ Ontario Government, Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, Social Assistance Trends – Ontario Disability Support Program, available at https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/open/sa/trends/odsp_trends.aspx; and Ontario Work, available at, https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/open/sa/trends/ow_trends.aspx.

⁸ Calculations do not include CPP, OAS, and GIS.

⁹ The author would like to thank ISAC colleagues for this insight.

Ricardo Tranjan is a senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Ontario office. Follow Ricardo on Twitter: @ricardo_tranjan