Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $60 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford has made many statements expressing how deeply concerned he is about the impact of COVID-19 on the health of Ontarians and our health system in general. In April, when the Canadian Armed Forces reported on conditions in certain long term care (LTC) facilities, Ford said, “The reports they provided us were heartbreaking, they were horrific, it’s shocking that this can happen here in Canada.” In September, he hailed the work of personal support workers: “Those PSWs, they’re overworked, they’re underpaid, and I’m going to make sure we take care of that… They went into an inferno and none of them complained. They went in there and they did their job and I’m just so grateful for all the PSWs out there.”

The premier has repeatedly asserted his government will “spare no expense to protect the health and safety of all Ontarians.” So we decided to investigate how that claim has played out thus far, in health care generally and long term care specifically.

Canada’s three largest provinces have had different experiences with COVID-19 in their health care sectors. During the first wave, British Columbia was widely praised for its exemplary response (and low death rate) in long term care facilities. Quebec and Ontario faced catastrophic outbreaks in long term care settings. As the months rolled by, though, both B.C. and Quebec have stepped up their pandemic responses in long term care facilities in a way that Ontario has not. In Ontario, the talk continued, but the actions fell short.

Context: A Legacy of Austerity Ontario entered the pandemic with an overburdened health system, as health care has been a frequent target for the austerity policies of successive Ontario governments. These policies have been wasteful and harmful to the health care system, the Ontarians that rely on it, and health care providers who staff it. In the last 25 years, successive governments have implemented ill-conceived austerity policies that failed and then had to be reversed.

The most recent periods of austerity were between 2011-12 and 2016-17 when health care spending grew at an average annual rate of 2.2%, far below what was needed to maintain existing services. The Financial Accountability Office estimated that, as a result of population growth, population aging, inflation, and other cost drivers, provincial health spending had to grow by 5.3% per year just to maintain the same level of service.

In 2018-19 to 2019-20, health spending rose by an average of 4.4%, still far short of the average 6.8% growth in spending in the 10 years prior to 2011-12. Shortly after taking power in June 2018, the Ford government planned a new round of austerity: the 2019 Fall Economic Statement projected health spending to increase by just 2% in 2020-21 and 1.1% in 2021-22.

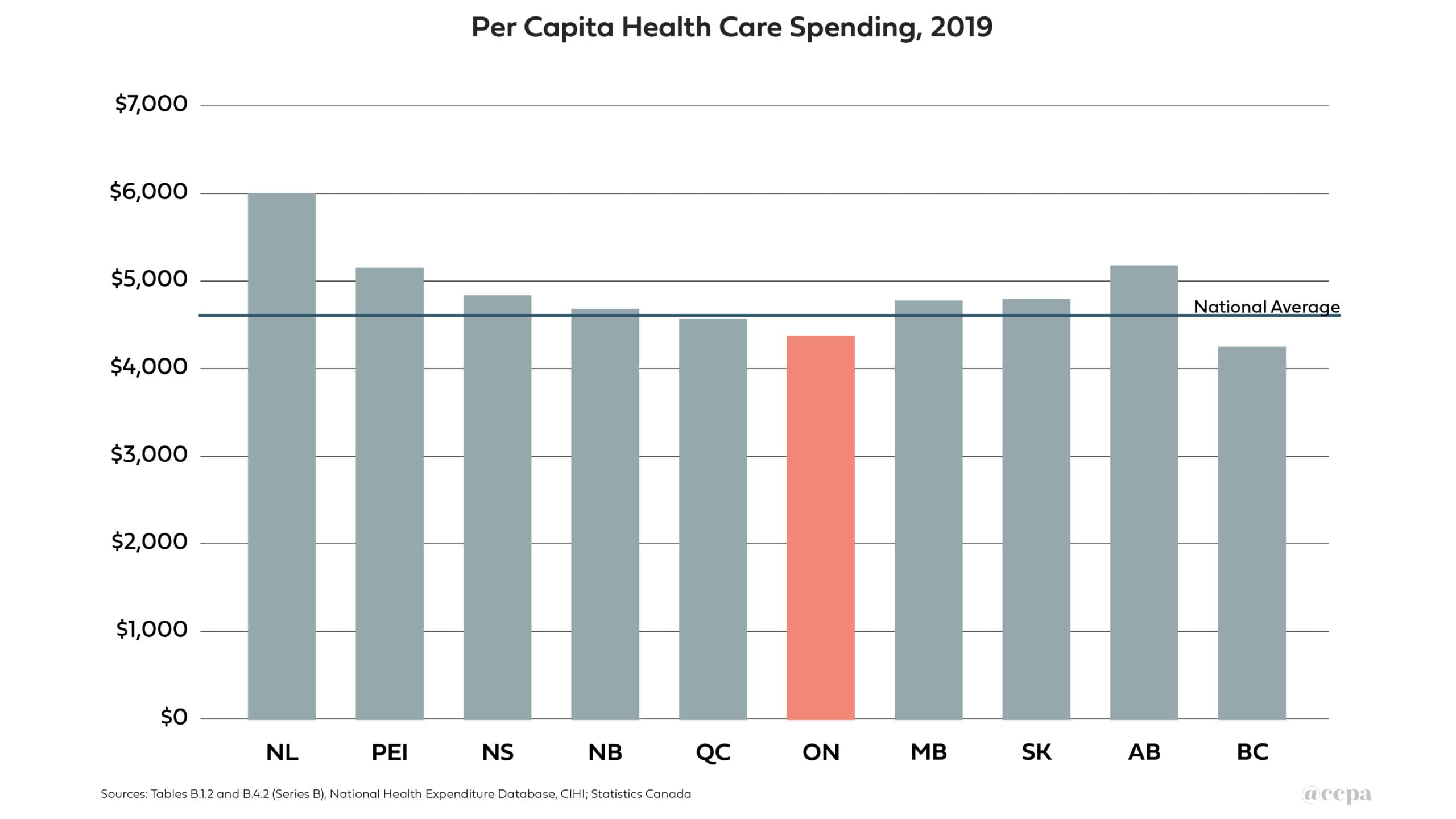

Chart 1 below shows that Ontario entered the pandemic as the province with the second lowest per capita health spending, significantly lower than the national average.

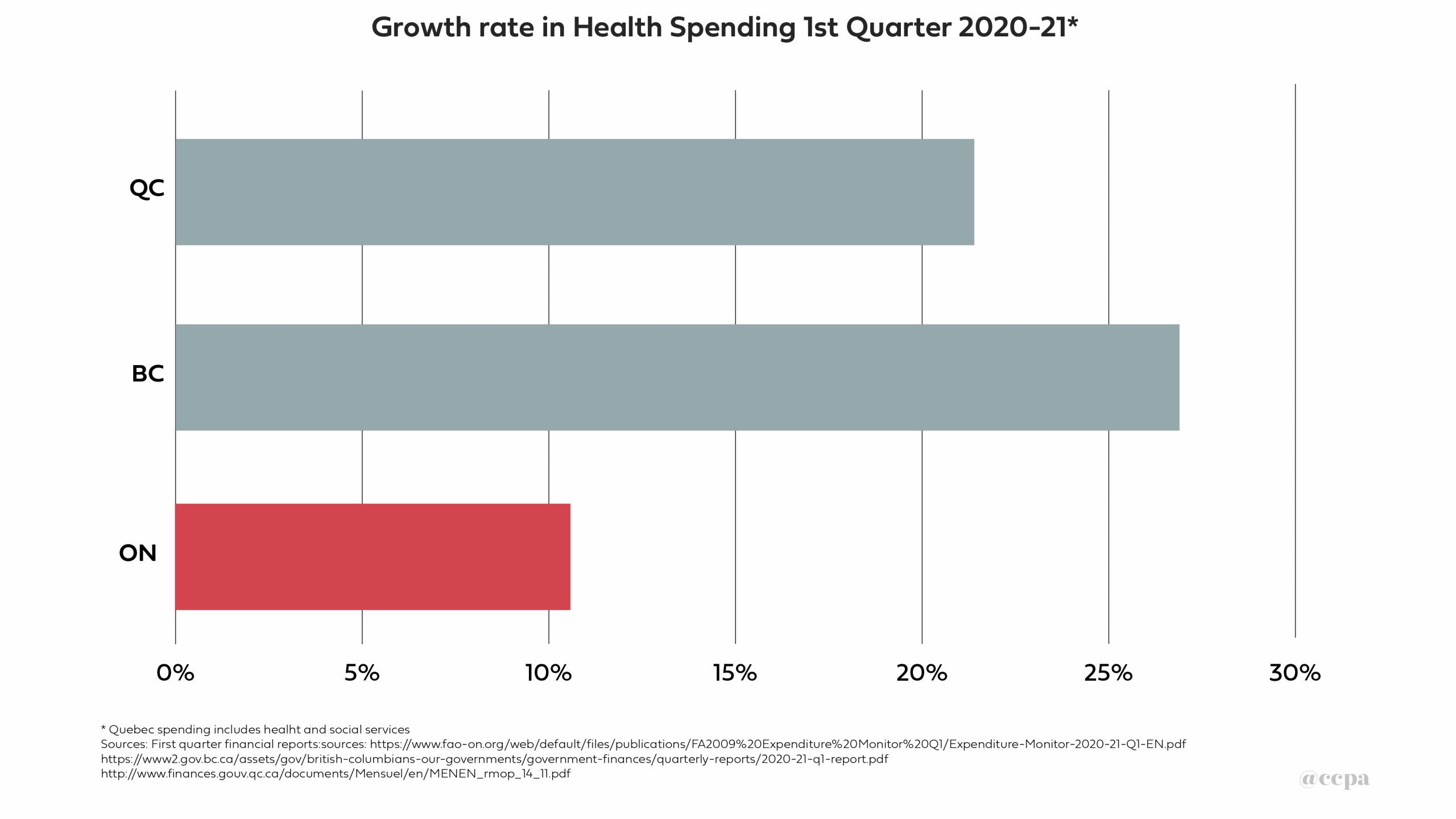

1st Quarter Spending Ontario’s lower per capita health spending would suggest that when the pandemic hit the Ontario government should have stepped up spending sharply in comparison to other provinces. However, that isn’t what happened. Chart 2 shows the increase in health spending from the first quarter of fiscal year 2019-20 (April-May-June) to the first quarter of 2020-21. As COVID-19 took hold in Canada, health spending in Ontario increased by 10.6%, less than half the rate of Quebec (21.4%) and B.C. (26.9%).

How did this lower spending affect health outcomes?

A recent analysis in the Canadian Medical Association Journal comparing LTC outcomes in B.C. and Ontario concludes that the tragic higher rates of infection and death in Ontario’s long term care homes were likely the result of a number of policy decisions that occurred prior to the pandemic. These included longer term problems like Ontario’s larger share of for-profit operators, lower funding levels, a larger proportion of shared rooms, a less comprehensive inspection regime, and less coordination between long term care facilities, hospitals, and public health agencies. However, these outcomes were also the result of government policies during the pandemic, the analysis suggests. The authors identified that Ontario lagged behind B.C. on comprehensive efforts on infection control and was crucial weeks later in requiring that staff work in only one facility.

To control infection and retain staff, B.C. mandated that all LTC work would be full-time work and staff would only be allowed to work in one facility. In contrast, Ontario’s response has contributed to the ongoing staffing crisis in the long term care sector. In Ontario, they are only allowed to work in one home but they do not have a guarantee of full-time work. As the Service Employees International Union has identified, personal support workers continue to bring home less money than they did before the pandemic. Further, in Ontario, the requirement to work in only one home does not apply to those who work for temporary staffing agencies. These are the workers that are least likely to have sick pay, and therefore most likely to face financial pressures to work while they are ill.

While Quebec had tragic results in LTC similar to Ontario’s in the first wave, it developed a much stronger policy response to prepare for the second wave. In June, Quebec began an aggressive program to train and hire 10,000 new long term care staff. In August, the province required that each facility have a manager responsible for the pandemic response with support from infection control specialists to address what the government had identified as problems in the response during the first wave. At the beginning of September, the B.C. government announced plans to hire an additional 7,000 staff in LTC and assisted living facilities.

At the end of September, the Ontario government announced $540 million in supports for LTC homes. These funds will be spread across staffing, PPE, infection control measures, and minor capital repairs. This was not accompanied by a mandate on staffing. Further, the $540 million is just 30 per cent of what we estimated it would cost to fund adequate staffing and pay caregivers enough to ensure adequate care for residents.

The experience of the first wave of the pandemic illustrated the crucial role of staffing and working conditions on the care and the very survival of residents in LTC. Despite calls from health care professionals, health care unions, advocates and family members to increase staffing in preparation for a second wave, the Ford government did not take this action. Despite claims about “spar[ing] no expense to protect the health and safety of all Ontarians,” it appears that quite the opposite is true and Ontario is careening towards yet another tragedy in this sector.

Sheila Block is a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Ontario office. You can find her on twitter at @SheilaBlockTO.