This year’s Alternative Federal Budget (AFB) was released on March 9. I was proud to be the primary author of its housing chapter. The first AFB exercise began in 1994, with the first AFB being published in 1995. That involved a joint effort between the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) and CHO!CES: A Coalition for Social Justice.Here are 10 things to know:

1. Job creation has always been a major focus of the AFB. People need employment to earn income and live fulfilling lives. New jobs also creates important goods and services that help the rest of us prosper. And the more people are working, the more taxes they pay, and the less we (as a collective) have to spend on poverty reduction initiatives (such as social assistance). The typeof jobs that get created matter too, as do working conditions; indeed, it’s important that people be happy in the workplace. Finally, whogets jobs matters —think gender, think racial diversity, think Indigenous peoples, think persons with disabilities.

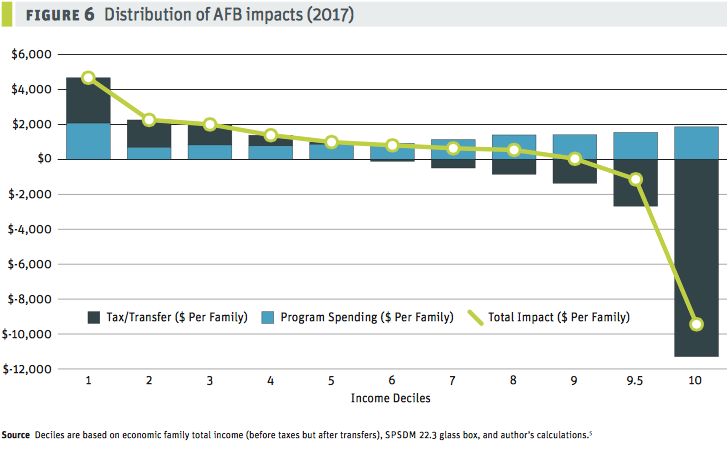

2. The AFB has always proposed a redistribution of income. This year’s document, for example, proposes a transfer of income (through our tax and transfer system) from households in the top six income deciles to those in the bottom four deciles; households in the top decile would the largest ‘loss,’ and households in the bottom decile would receive the lion’s share of the transfer. The AFB proposes to do this in part by closing tax loopholes for companies and high-income individuals. It also proposes to make our income tax system more progressive and to spend more on important social programs. This proposed transfer of income is illustrated in the figure below (which I’ve ‘cut and paste’ from the Macroeconomic Policy chapter of this year’s document).

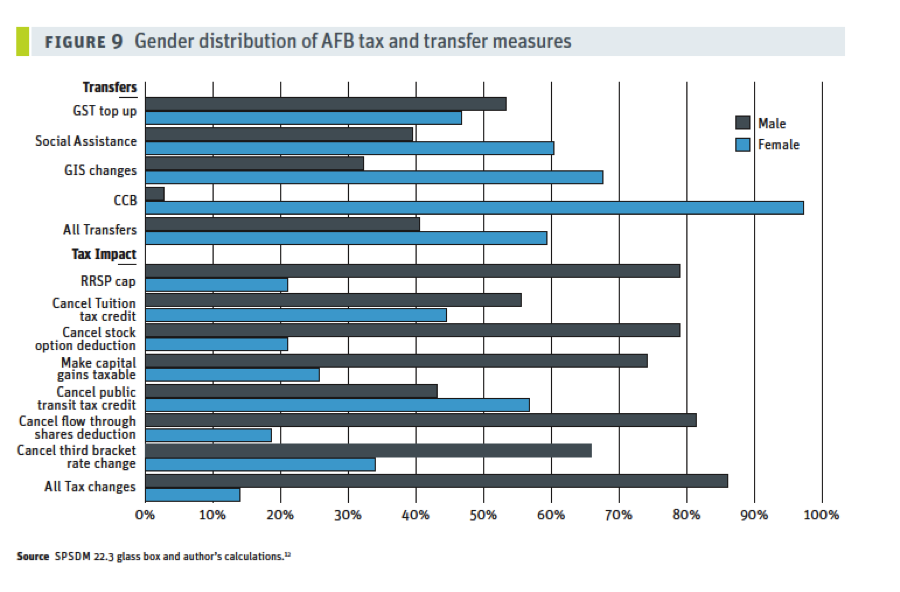

3. Gender equality has always been one of the AFB’s major priorities. According to Paul Leduc Browne, the project has always “stressed policies to both recognize the importance of unwaged labour (domestic and volunteer work) and to increase the participation of women in wage labour. These included investment in child care, but also changes to the unemployment insurance, social assistance, family allowance, and pension programs” (Leduc Browne, 2003, p. 40). The following bar graph from this year’s AFB illustrates the estimated, direct financial impact of this year’s AFB on gender (this too has been ‘copied and pasted’ from the document’s Macroeconomic Policy chapter).

4. In the mid-1990s, the project had a strong focus on monetary policy.[1] At that time, the Bank of Canada had raised interest rates to the point where holders of financial wealth did well (because they got good rates of return on their savings). But these high interest rates also made it expensive for both businesses and governments to borrow money to create new jobs; it also made it expensive for all orders of government to service public debt they’d already incurred. All of this resulted in slow economic growth, high unemployment and immense pressure on social programs.

5. The AFB has always had an impact on public policy, even in the early years. Every year, for example, AFB working group members have briefed members of the Liberal and New Democratic Party (NDP) caucuses at the federal level.[2] According to Paul Leduc Browne: “[I]n the earlier years, the finance minister himself always read our budget; until 1999, we had a meeting with him each year after the publication of our alternative budget” (Leduc Browne, 2003, pp. 41-42). More recently, it’s abundantly clear that the Trudeau Liberals’ 2015 campaign platform was strongly influenced by the previous year’s AFB. In fact, staff at the CCPA estimate that 30% of the previous year’s AFB found its way into the Trudeau Liberal platform.

6. The forecasting done for the AFB has proven more accurate than that done by the federal government. As Bruce Campbell notes: “The AFB gained credibility within policy circles and the media not only for its sophisticated fiscal framework, but also for its accurate predictions of emerging budgetary surpluses between 1999 and 2004. Year after year our forecasts were much more accurate than those released by the Department of Finance, which tried to hide the surplus—money that could have been put back into social programs…” (Campbell, 2015, p. 26). This helped spur the creation of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, which the AFB had recommended.

7. This exercise brings together like-mind people across the country and across sectors. As Paul Leduc Browne writes: “The project has brought together a wide range of groups and individual citizens from many sectors of civil society: labour, students, women, churches, anti-poverty groups, Aboriginal organizations, child care, health care, education, housing, farm coalitions, environmental organizations, international development NGOs, and other social and economic justice groups” (Leduc Browne, 2003, p. 37). Bringing together people and groups also means encouraging healthy debate and tensions. “The important point is that such tensions are healthy; I feel we were fortunate to experience them” (Leduc Browne, 2003, p. 41).

8. This exercise has done an excellent job of embracing bilingualism and partnering with Quebec-based contributors.The full document has always been published in both English and French. Given the length of the document, that shows a very strong commitment to empowering French-speaking audiences and bridging what has sometimes been referred to as Canada’s “two solitudes.” What’s more, Quebec-based unions and civil society groups have participated in the project.

9. There have now been alternative budgets in five Canadian provinces. Those provinces are British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia. Most of these efforts have been coordinated by the CCPA. There have also been municipal alternative budgets, including in Halifax and Winnipeg.

10. Soon, Alberta will have its first alternative budget. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, a group of volunteers recently took an initial step toward an alternative budget for Alberta. Building on a series of discussions with individuals in the province’s nonprofit sector, labour movement and advocacy sector, we produced a document seeking to provide a foundation for moving toward an alternative budget. We hope this becomes an annual exercise in Alberta, and we hope the project’s scope increases each year.

The author wishes to thank Bruce Campbell, David Macdonald, Gayle Rees, Erika Shaker, John Smithin and Armine Yalnizyan for invaluable assistance with this blog post. Any errors are his.

Nick Falvo is Director of Research and Data at the Calgary Homeless Foundation. His area of research is social policy, with a focus on poverty, housing, homelessness and social assistance. Nick has a PhD in public policy from Carleton University. Fluently bilingual, he is a member of the editorial board of the Canadian Review of Social Policy/Revue canadienne de politique sociale. Follow him on Twitter @nicholas_falvo.

[1] Admittedly, monetary policy is not, strictly speaking, a budget issue. However, budgets (and alternative budgets) provide an opportunity to discuss the main contributors to unemployment.

[2] I’m told that, while in opposition, members of the Liberal caucus paid more attention to the AFB than did members of the NDP caucus.