Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

It is now abundantly clear – if it wasn’t already – that the Saskatchewan government’s “transformational change” agenda is in reality a not-so-subtle euphemism for province-wide austerity in response to the current economic downturn. Recently announced spending cuts in health ($63.9 million), education ($8.7 million) and social services ($9.2 million), coupled with the programming and funding cuts from the previous budget is clear evidence that the government’s plan for the economy is to “cut its way to growth.”

The problem with this plan is that is exactly the worse possible course of action to take while the province is mired in economic stagnation.

As a late-comer to economic downturn, Saskatchewan at least has the advantage of being able to assess the efficacy of policy responses by those who have gone before us as national and state-level governments across North America and Europe have sought to effectively respond to the economic downturn inaugurated by the 2008 financial crisis. What this wealth of examples clearly demonstrates is that austerity measures undertaken during an economic downturn have the perverse effect of prolonging economic stagnation, increasing unemployment, exacerbating deficits and hindering economic recovery.

The United States offers a useful economic laboratory to assess the efficacy of austerity measures during an economic slump. Since the start of the Great Recession, twenty U.S. states adopted varying degrees of public spending reductions as the best means to address the downturn, while thirty states adopted varying degrees of expanded public spending. Surveying the results of these divergent responses to the economic recession in the United States, we see that states that adopted an expansionary fiscal policy were able to pull themselves out of recession sooner, while experiencing less of the negative economic impacts of the recession.

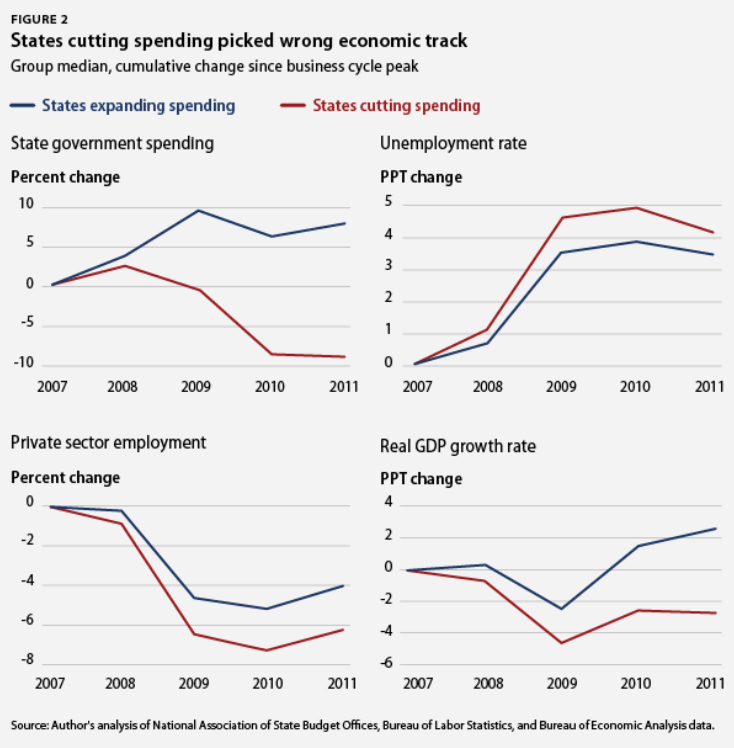

As Figure 2 illustrates, states that adopted an expansionary fiscal policy experienced less unemployment, higher private sector employment growth and significant growth to GDP in comparison to those states that adopted wide-spread spending cuts. Indeed, the greatest divergence between states was in economic growth. Expanding states accelerated well ahead of their prerecession growth rates while cutting states languished with growth much slower than before the recession. At the worst of the recession in 2009, GDP growth in expenditure-expanding states was on average 2.4 percentage points below the prerecession pace of growth. Expenditure-cutting states fell much deeper into the recession hole, with their GDP growth rates on average falling 4.6 percentage points below their prerecession level.

The negative experience of these states that adopted austerity should not come as a surprise. Despite the prevailing economic orthodoxy that austerity measures can restore growth during an economic downturn, actual empirical evidence of this occurring is in very short supply. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – once a champion of fiscal austerity – has been forced to admit this. Assessing 30 years of evidence, the IMF unequivocally concludes: “In economists’ jargon, fiscal consolidations [austerity] are contractionary, not expansionary. This conclusion reverses earlier suggestions in the literature that cutting the budget deficit can spur growth in the short term.”

Moreover, the IMF demonstrates that adoption of austerity measures during an economic downturn is “likely to lower incomes—hitting wage-earners more than others—and raise unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment.”[2] Such effects will have the consequence of exacerbating deficits as falling incomes diminish government tax receipts while growing unemployment puts fiscal pressure on social supports like employment insurance, social assistance, re-training allowances, etc. Thus, attempts to cut spending to tame deficits may have the perverse effect of increasing existing deficits, as prolonged economic stagnation taxes both government revenues and social spending. In light of this, the IMF advises governments to consider delaying deficit-fighting measures until a more robust economic recovery is evident.

[1] Laurence Ball, Daniel Leigh, and Prakash Loungani (2011). “Painful Medicine.” Finance and Development, September 2011, Vol. 48, No. 3. Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2011/09/ball.htm

[2] Ibid.