Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

One hundred years ago—July 1, 1923—the Canadian government passed “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration.” Known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was an overtly racist law prohibiting the arrival of newcomers from China. It also required all people of Chinese heritage, including the Canadian-born, to register with the federal government in order to stay in the country. Chinese Canadian communities across the country mobilized to lobby against the act but in the end their efforts failed to stop its passage. Thus, July 1 came to be known as “Humiliation Day” for many Chinese Canadians.

On the 100-year anniversary of the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The Monitor is releasing a series analysing the context in which the Act passed, resistance to the law, and its historical legacy. These articles are a serialization of the booklet 1923: Challenging Racism Past & Present, which you can read in full at https://challengingracism.ca/

Read the full series

This article is one piece of a larger series, which looks at the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act, 100 years after it passed in 1923.

We will update this list with hyperlinks as the series is released.

Chapter 1: Challenging Racism, 1912-1914

Chapter 2: Anti-Racism and the War, 1914 – 1916

Chapter 3: The Revolts, 1917-1919

You are here: Chapter 4: Global Challenges to Racism, 1919-1922

Chapter 5: Backlash, 1920-1922

Chapter 6: The Chinese Exclusion Act and More, 1923

Echoes of 1923?

The anti-racist and labour movements that rocked Canada in 1919 were part of a broader wave of cataclysmic change following the end of World War I. 1919 was a momentous year in the global fight against white supremacy, with anti-colonial resistance taking place in Egypt, Korea, China, and India, alongside a burgeoning pan-African movement that envisioned Black liberation as an international struggle. Russia’s successful communist revolution of 1917 also threatened the global status quo. In response, Canada and other imperial powers sent military forces known as the Siberian intervention.1

The Paris Peace Conference took place in Versailles in 1919 in order to negotiate a peace agreement and divvy up control of territory amongst nations that won the war. Despite hopes for national and ethnic self-determination, Versailles actually reinforced the victor’s imperial division of the world. In Canada, politicians from Victoria to Ottawa looked to Versailles to defend and consolidate Canada’s racist and colonial interests.

White Supremacy at Versailles

Beginning on January 12, 1919, the Paris Peace Conference at Versailles brought together the representatives of the victorious powers of World War I, including the big four – France, Britain, Italy, and the United States – as well as Japan, which was a junior imperial power. Along with others, including a delegation from China, they met to determine the terms of peace, including what to do with former territories controlled by Germany and the Ottoman Empire.

In the process, the major powers redivided the world, and promoted what would become the League of Nations. While some independent nations emerged from the process and the losing imperial powers were dismantled, many nations hoping for independence were left just as subjugated as before the war: either by new, or existing, imperial countries.

}},213570:{type:copy,enabled:true,collapsed:false,fields:{copy:

Prior to the conference, Canada’s prime minister Robert Borden promoted an imperial Anglo-American alliance between Canada, England, and America to U.K. prime minster Llyod George. In a letter to George, Borden described the role of such an alliance as “undertak[ing] worldwide responsibilities in respect of undeveloped territories and backward races similar to, if not commensurate with, those which have been assumed by or imposed upon our own Empire.”

This call to create an Anglo-American bloc to dominate the world under the guise of the ‘white man’s burden’ was an extension of the civilizing mission that led to genocide against Indigenous peoples in Canada. Buttressed by white supremacists in California and British Columbia, Borden saw Versailles as an opportunity to organize the power of white people and nations over Indigenous and racialized peoples.

BC Legislature Messages Versailles

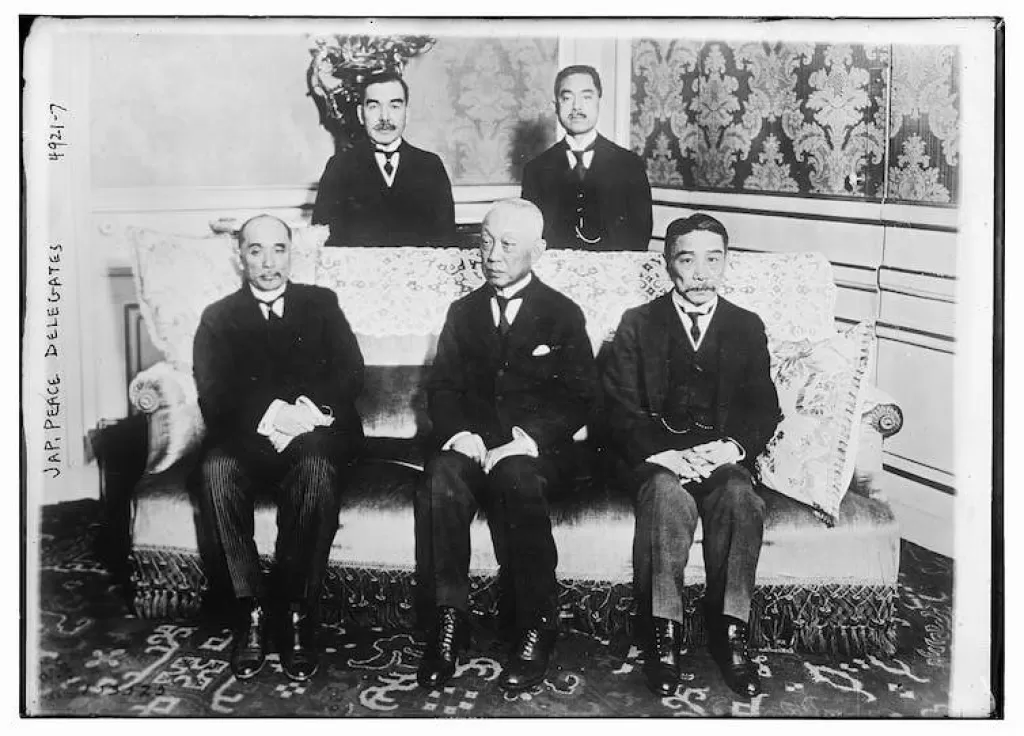

Japanese delegates to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Photo: Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540.

The end of the war saw BC legislators messaging prime minister Robert Borden in Versailles and demanding that he uphold and defend Canada’s right to maintain anti-Asian immigration policies. The first resolution, passed in March 1919, resolved that “Canada’s representatives at the Conference be asked to adhere firmly to the principle that Canada shall always exercise full control over immigration to this Dominion.”

A month later, the legislature again resoled “to urge upon the Peace Conference, as a matter of the immigration into Canada of those races which will not readily assimilate with the Caucasian race.”

Racial Equality Clause

Although Japan was an imperial and colonial power in Asia, the Japanese delegation to Versailles had a stake in fighting white racism abroad, as its diasporic population endured racist policies and attitudes in settler colonial nations such as the US, Canada, and Australia. The delegation proposed that a racial equality clause be included in the proposed charter for a new League of Nations. That proposal met stern opposition from the British delegation (which included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa) as well as the US.

A watered-down version of the clause achieved majority support, but was vetoed by US president Wilson. Wilson’s veto reflected the power of white supremacy at Versailles – as well as the complex global race hierarchies that could see an imperial ally like Japan struggle to make headway when its interests conflicted with more powerful, white imperial nations.

The International Labour Organization (ILO)

The formation of a labour organization was part of the discussions at Versailles. The proposed charter for the ILO originally included the clause, “in all matters concerning their status as workers and social insurance, foreign work men lawfully admitted to any country and their families should be ensured the same treatment as the nationals of that country.” Opposed by Canada and others, Borden personally took the initiative to eliminate that clause because it would offend provinces such as British Columbia, which reserves certain industries for white labour.”

The Mandate System

The new League of Nations embraced the liberal imperial concept that countries such as the US, the U.K., and Japan had a ‘civilizing mission’ regarding former enemy territories that were part of what today is known as the Global South. Thus, rather than granting independence to such territories, they were placed under the control of specific imperial powers. For example:

- France was given control of Syria and Lebanon;

- the U.K. was given control of Palestine, Transjordan, and territories in Africa.

- Japan was given control of several Pacific Islands, today part of Palau, the northern Marianas, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands. Versailles also recognized Japan’s seizure of Shandong in China.

Earlier, the United States successfully pressured participants to recognize the Monroe Doctrine, a foreign policy that opposed European intervention in the Americas while naturalizing the US’s exclusive right to meddle in other countries in the western hemisphere.

While Versailles could have been an opportunity to forge a world system based on mutual respect for national self-determination, it instead represented the triumph of white supremacy and racial capitalism, only making changes that extended and sustained the domination of Anglo-American empires.

Fighting Exclusion at Versailles

Racialized and colonized peoples were already demanding a voice in their future when the peace conference convened in 1919. Many came to Versailles with the hope of lobbying world leaders and claiming their rightful place in a better world. These protests augured the onset of decolonization.

Among those who exposed the relationship between racism and empire was the prominent African American activist W. E. B. Du Bois. He was a key organizer of the Pan-African Congress, linking colonialism in Africa with the oppression of African Americans. The congress gathered in Paris during the peace conference but was denied access to the official proceedings.

Instead, fifty-seven delegates, including two women, Helen Noble Curtis and Addie Waites Hunton, who represented fifteen countries had their own meeting at a separate location. Other Black leaders in that era, including Marcus Garvey, would criticize the Pan-African Congress for being too moderate in its demands. The Pan-African Congress would remain an important if moderate voice for decolonization in subsequent years.

Also present at Versailles was a representative of the Korean independence movement against Japanese occupation. Kimm Kyusik travelled with the Chinese delegation to Paris. Other Korean representatives in the US had been refused passports by the state department and were prevented from attending. Nevertheless, Kimm appealed to the Versailles conference and various governments, only to be refused any standing at Versailles or even a response to petitions and appeals for recognition.

The US and other imperial powers had appeased Japan’s expansion in Korea as early as 1905. At that time, the US secretly recognized Japan’s control of Korea in exchange for Japanese recognition of US control over the Philippines.

The Group of Annamese [Vietnamese] Patriots was also present in Paris and activists such as Phan Văn Trường, Phan Châu Trin, and Hồ Chí Minh drew up a petition to the French government, then in control of Vietnam, demanding freedom of the press, release of political prisoners, and self-determination. They also sent the petition to the US and other delegations at Versailles. The petition was met with indifference but represented a step on the road to decolonizing Vietnam.

Decolonizing Insurgencies

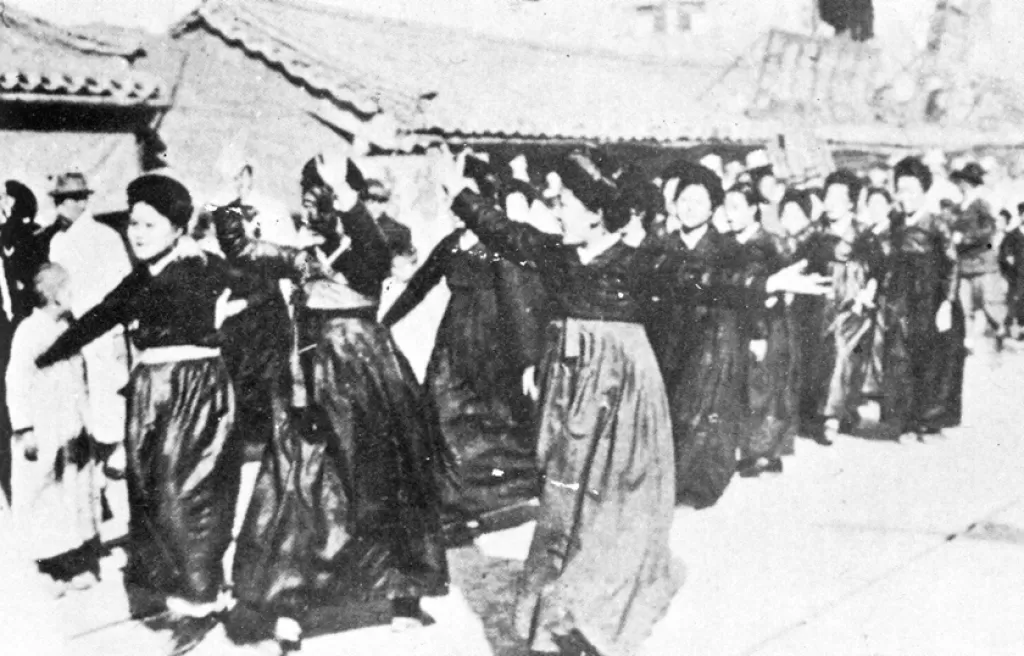

Female students participate in the March 1, 1919 movement demonstrations. Image source: Korean Quarterly

During and after Versailles, a global wave against colonialism and racism swept across the continents, as activists in the colonies demanded freedom from imperial rule, no doubt in some cases, as a response to the disappointment of the post-war peace treaty.

March 1st Movement (Korea)

Among those standing up for national liberation at this time were the Korean people. Simmering opposition to Japan’s 1910 annexation of Korea broke into open rebellion on February 8, 1919, when Korean students studying in Tokyo, with young Japanese allies, wrote and released an independence manifesto at the Tokyo YMCA. In Seoul’s Pagoda Park, demonstrators there read another declaration of independence on March 1.

This was the sign for a massive uprising involving millions of demonstrators across Korea demanding independence from Japan. Frederick Arthur McKenzie, a Canadian correspondent, noted, “The most extraordinary feature of the uprising of the Korean people is the part taken in it by the girls and women.”

Japanese imperial forces responded with a brutal crackdown, killing and arresting thousands including 17-year-old Yu Gwan-Sun who was imprisoned after helping organize demonstrations in her hometown. Tortured, she died in prison in September 1920. March 1st became an emblem of national independence. Korea finally won its freedom after the defeat of the Japanese empire in 1945. It was arbitrarily split into north and south by the Allies, and descended into civil war, a state that continues to this day.

May 4th Movement (China)

d 3,000 students from 13 universities in Beijing gathered in Tiananmen Square on May 4, 1919 to oppose Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles, which gave territories in Shandong to Japan.

The Chinese delegation at Versailles actively worked to regain control of Chinese territory formerly controlled by Germany. The US and the U.K., however, agreed that Japan could take over those territories, which had been occupied by Japanese imperial forces during the war.

This decision provoked huge protests in China, known as the May 4th movement. Thousands of students from campuses around Beijing gathered in protest of the betrayal at Versailles and the weakness of the Chinese government.

The movement spread to campuses across the country with merchants and workers organizations also participating. May 4 marked the beginning of cultural and political movements in which traditional Confucian values came under fire, inspiring many who would become future leaders of the Chinese communist movement.

Egyptian Revolution

The British government had substantial control over Egypt from 1882 and declared it a ‘protectorate’ when the 1914 war began. After the armistice, Saad Zaghlul and other nationalist leaders demanded an end to the protectorate and the right to attend Versailles as an independent delegation.

Zaghlul and the Wafd (Delegation) party developed strong ties with the Egyptian people. When the British exiled Zaghlul and other Wafd leaders to Malta to stop them from traveling to Versailles, the country rose up in mass demonstrations and partisan attacks against the occupation, only to be met by British violence. Over 800 people died and hundreds more were injured. The British government was forced to recognize Egyptian sovereignty but retained power in the country by maintaining control of Egypt’s foreign affairs and by keeping its troops in the country

Egyptian women addressing a crown at a protest

Jallianwala Bagh

April 13, 1919 marked the harvest festival of Baisakhi, and for Sikhs, the celebration of the birth of the Khalsa tradition, founded by Guru Gobind Singh. On this day, a public meeting was convened in Amritsar, Punjab, India, to challenge the British Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act (Rowlatt Act), which banned public gatherings, imposed a curfew, and criminalized dissent.

An estimated 20,000 people had gathered when British Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer ordered the British Indian Army to begin firing, without warning or provocation, at men, women, and children. Though official accounts reported 379 people killed and 1200 wounded, many scholars, activists, and medical professionals present at the time argued that the death toll was much higher.

This slaughter ignited and reinvigorated the anti-colonial movement that had been sweeping the Indian subcontinent for decades. For many, it would mark the single greatest catalyst that would finally rid India of its British rulers in 1947.

Global Black Resistance

The war and its immediate aftermath birthed both moderate and radical streams of resistance among Black movements in England, America, and the Caribbean. For the hundreds of thousands who had participated in the war, there was a growing confidence and an expectation of fairer treatment upon return to civilian life. This was a major factor that inspired a Black resistance movement in 1919 that ended in unparalleled confrontations and anti-Black riots. In Britain alone, anti-Black riots broke out in nine British port towns, including Liverpool, leaving five people dead, hundreds arrested, and many more detained for ‘protective custody.’

In the United States, a new determination to resist white supremacy emerged alongside heightened anti- Black violence. In 1919 alone, there were seventeen anti-Black riots, often precipitated by police violence against Black demonstrators trying to protect themselves or their communities. The Tulsa anti-Black massacre of 1922, directed at the successful Black community in Tulsa, ended with as many as 300 people dying. Though initially sparked by rumours of a Black man accosting a white woman that were later proven to be false, the mob action was undergirded by Jim Crow laws that enforced segregation and the competitive desire to own and control land.

Similarly in the Caribbean, Black peoples of the islands and surrounding areas stood up to discrimination and colonialism. Among the 1919 resistance movements of that era is the little known Black Revolution in Belize (then British Honduras), which saw returned servicemen march down the centre of Belize Town to protest their poor treatment during the war and the systemic discrimination they faced upon their return. They were joined by thousands of others. For many in Belize today, this uprising marked the first shot in the quest for independence from the British.

The anti-racist and anti-colonial uprisings of this year marked the onset of global decolonization. Unfortunately, a global white backlash also arose, signaled by Versailles and prolonging the struggle for decades. This was also the case in Canada.