April Labour Force Survey Key Facts:

- 3 million lost jobs, but another 2.5 million had a majority of their hours cut.

- 5.5 million Canadians lost work or a majority of their hours since February.

- 2 in 5 youth (aged 15 to 24) lost jobs or a majority of their hours.

- Half of workers making <$16/hr lost their job or the majority of their hours.

- All jobs created since September 2005 have now been lost.

We thought the March jobless numbers were bad, but it is almost a good news story compared to what we saw today in the April figures.

The unprecedented closure of major sections of Canada’s economy in mid-March is finally being reflected in the jobless numbers today. Of course, without those closures we would be in a historic health crisis with emergency rooms completely overflowing and our health system shutting down, as we saw elsewhere.

In that sense, this shutdown was exactly the right thing to do. I look at these unprecedented joblessness numbers and think: this is how we protected many workers from contracting the virus—though they sacrificed their income.

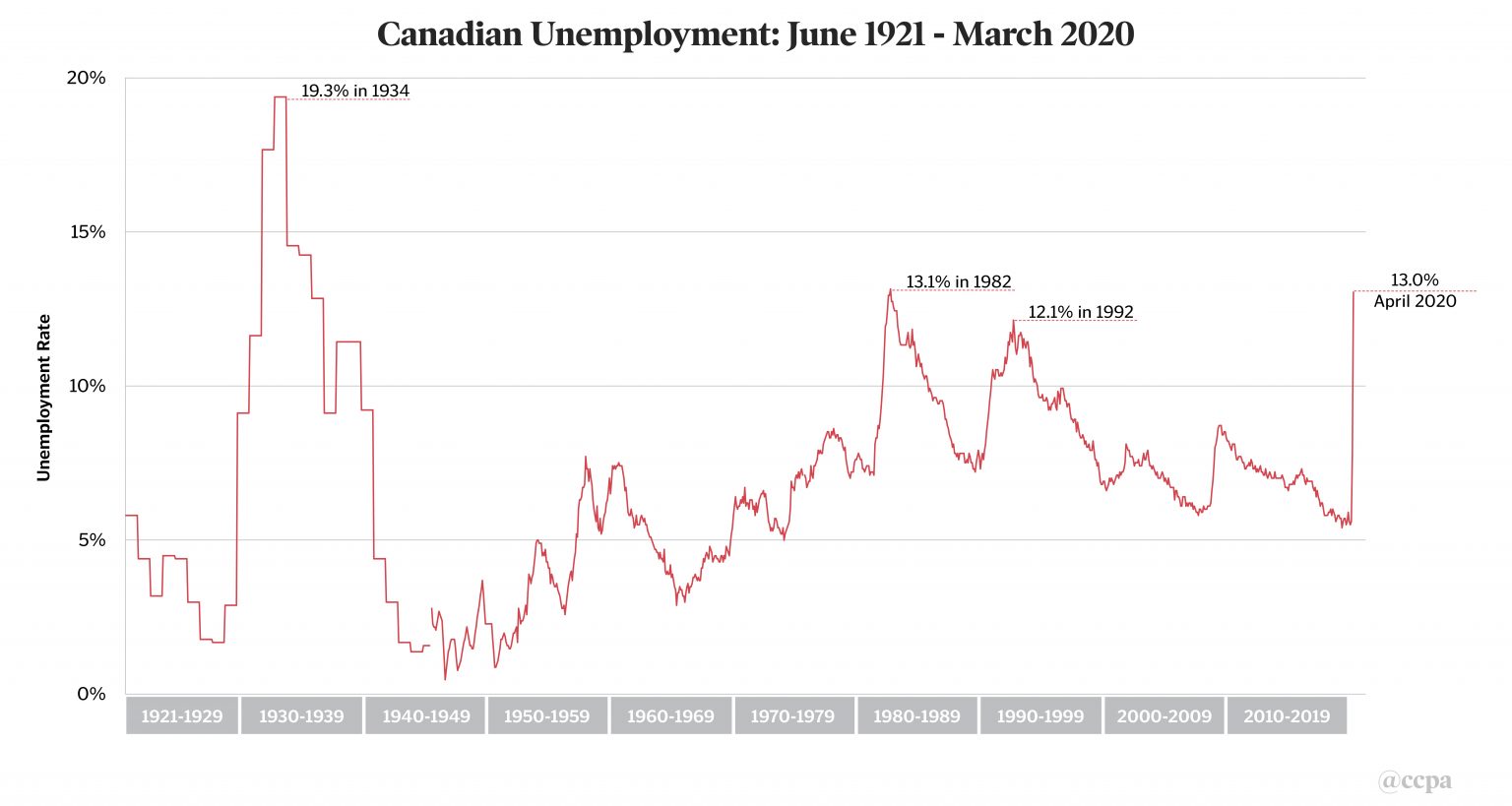

The official unemployment rate for April is 13.0%. This is a historic high. There was a single month, Dec 1982, where unemployment was slightly higher at 13.1%. But after that one month, you’d have to go back to May 1936 at the end of the Great Depression to see anything similar. Put another way all jobs created since October 2005, 15 years ago have been lost by April 2020. While the March data was collected as the shutdown was in progress during the third week of March, the April figures show the full impact of a month’s worth of pandemic lockdown.

Source: Statistics Canada table 14-10-0287-01, Cansim vector v2062815 & historical series D124-133

Unfortunately, the labour market picture is much worse than implied by the unemployment rate. Unemployment hinges on people looking for work, and if you aren’t looking (because the economy is shut down) or if you’re “employed” but with no shifts, you don’t count as unemployed.

Furthermore, there has been a tremendous loss of hours, even if workers are still getting some income. Put all those factors together and a shocking 29% of those working in February had lost their job or the majority of their hours by April.

We can see the real impact of loss of employment but, also, of loss of working hours across Canadian cities, gender, incomes, and age in the table at the end of this analysis.

In some ways this was entirely predictable, given that as of April 19th (the last day of the April LFS survey period), 35% of all those employed in February were receiving the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB).

To receive the benefit, workers would have to be laid off, be employed with no hours or be making less than $1,000 a month.

As of May 5th, the most recent data, 40% of those employed in February were receiving the emergency benefit. While today’s job and hour losses may be predictable, it’s still shocking to see it come through in the LFS figures.

All told, more than 3 million Canadians who had a job in February no longer did in April.

This includes both the officially unemployed and those who are not looking for work because of job scarcity. Another 2.5 million Canadians remain employed, but have lost at least half of their hours. In total, 5.5 million Canadian workers—29% of all workers—have been laid off or seen big reductions in their hours since February.

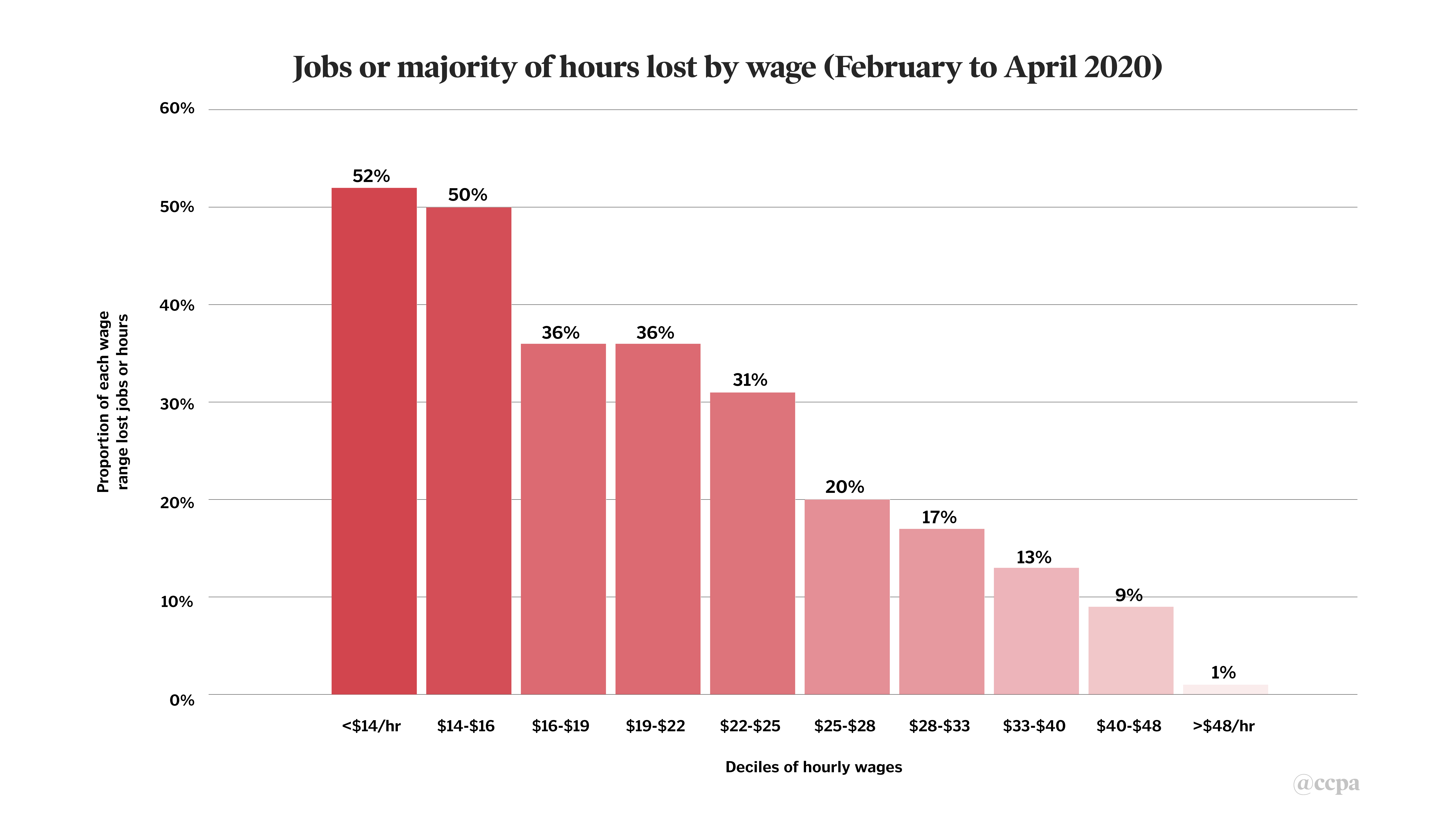

The breakdown by hourly wage is the most shocking of all—the impact of the pandemic lockdown hasn’t been felt equally by all Canadian workers.

Half of all those earning $14 an hour or less have been laid off or have lost all their hours.

This compares to only 1% of jobs lost or hours cut among the richest 10% of workers who make more than $48 an hour.

For low wage workers, who are far more likely to be renters, that may mean two full months of rent due with no regular income coming in. While mortgage holders can defer payments to the end of their terms, there has been no similar federal help for renters except a moratorium on evictions which doesn’t pay back rent.

Youth (aged 15 to 24) are typically hit hardest during an economic downturn and this time is no different: they saw massive job losses in March and things have only gone downhill from there. In April, 43% of youth lost their jobs or most of their working hours.

Take this in: 26% of workers aged 25 to 54 lost their job or working hours in April.