Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

This analysis has been updated following federal legislative changes. Read the update here.

Fast Facts:

- More than 4 million Canadians will be affected when the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) winds down on September 27.

- 2.1 million CERB recipients will be eligible for CERB’s replacement, Canada’s revamped Employment Insurance (EI)—but 781,000 of them won’t be automatically ported to EI. They will have to manually apply and hope for success.

- Almost a half million—482,000—CERB recipients won’t transfer to anything else and will stop receiving federal income supports all together.

- On average, CERB recipients will receive $377 a week pre-tax from the various CERB replacement programs, including EI. By comparison, CERB has provided $500 a week, with no taxes withheld.

-

2.7 million (or 74%) of CERB recipients will be worse off after CERB ends:

- 1.6 million women on CERB will be worse off financially after the switchover, compared to 1.2 million men.

- 605,000 CERB recipients in Toronto will be worse off financially after the switch along with 299,000 in Montreal and 260,000 in Vancouver.

- 336,000 additional Canadians who didn’t qualify for CERB could gain support through EI after it restarts on September 27.

- Detailed recommendations follow the analysis.

The transition from CERB to EI changes things for millions of Canadians

On September 27, roughly four million Canadians will be transferred off the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). The majority will move to Employment Insurance (EI) or to a suite of new “Canada Recovery” programs, the details of which have only been recently announced.

These include the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB), Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit (CRCB) and the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit (CRSB). They provide a flat rate of either $400-a-week (CRB) or $500 (CRCB & CRSB).

The new recovery programs have yet to be passed by the federal minority parliament and, thus, are only proposals. Given the recent prorogation of the House of Commons that ends with the Speech from the Throne on September 23, parliamentarians have a short window of only four days in which to pass the legislation that would create these recovery programs—although the EI changes have already been implemented by Interim Orders.

Unlike CERB, these new programs will withhold taxes from the flat amounts. These programs will also be retrospective; CERB was prospective—people got support for the upcoming period.

For its part, EI will have a $400-a-week benefit floor and its entrance requirements will be reduced to a universal 120 insurable hours. EI’s payments have always had taxes withheld.

Who is impacted by the transition from CERB?

As of September 6 (the most recent data available), 4.03 million people had received CERB in the previous period (two weeks if they were receiving it from Employment and Social Development Canada or four weeks if it was from the Canada Revenue Agency).

Throughout August, the total number of active CERB recipients has remained relatively stable at just over four million, with only a small number of new applicants. In other words, CERB recipients in August had almost all lost their job or usual earnings prior to the start of the month.

The four million CERB recipients in August is far below the total number of unique applicants who have received CERB at any point since March 15, which stands at 8.75 million. Over half of those who have received the CERB since March 15 have now returned to the labour market or have switched to the wage subsidy.

Figure 1: Count of active CERB recipients by source of application

While detailed statistics of who is receiving the CERB or who might receive benefits from its replacements are not available, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) provides sufficient data to estimate who might be eligible for the new programs and how much they might receive from them (see the methodology for more details).

This analysis, which draws on LFS PUMF data, identifies 3.7 million CERB eligible Canadians, although we know there were 4.0 million CERB recipients in the second week in August. Therefore, there are 300,000 CERB recipients whose characteristics are unknown and it is unclear how they will fare in the switchover. My suspicion is that they are low-paid gig workers, making under CERB’s $1,000/month ($250/week) limit. The LFS does not collect income data on the self-employed and, despite my best efforts, I suspect those workers are being under-represented. Unless otherwise stated, all numbers in this analysis are a result of the LFS PUMF simulations.

Table 1 summarizes where those four million CERB recipients might end up after September 27th. Just over half (2.1 million) will be eligible for EI in one form or another.

Almost 900,000 CERB recipients could move to the new CRB. Most of these claimants are self-employed and lost work, but some will have been past EI recipients whose benefits ran out in 2020.

The CRCB will likely cover 184,000 CERB recipients at the outset. This is mostly due to the lack of child care options or closed schools, although it will also support a small number people, likely women, who quit work to care for a family member. The criteria for the CRCB are stricter than for the CERB: the child has to be under 12 years old, hours must have dropped by at least 60%, and the parent can’t be keeping a child home voluntarily. The CERB criteria on this front were more relaxed.

A small number of Canadians may immediately claim the CRSB, the new sickness benefit, but it can only be used for a maximum of two weeks, meaning it will quickly run out.

A disturbingly high number of CERB recipients will crash out on Sept 27: over half a million Canadians won’t have a replacement support program once CERB ends. Among those, 70,000 will technically qualify for EI’s Working While on Claim provisions, but they will make less than $50 a week. At such a low pay rate, most likely won’t bother with the bi-weekly EI reports.

Another 43,000 people receiving CERB will hit the CRB income cap as of August and likely won’t apply for it (CRB has a fifty cents on the dollar clawback for those with net incomes over $38,000 in 2020, excluding their CRB benefits).

That leaves 412,000 workers without support—mostly low wage earners and with few hours before COVID-19—who had their work disrupted but then returned fully to their previous low-wage, low-hours job. They were eligible for CERB, but neither EI nor the various new programs will cover them. They will fall through the cracks.

There is the question of whether low wage workers who have gone back to their pre-COVID earnings should be receiving federal support. If implemented incorrectly, these wage supports can easily encourage employers not to give low wage workers a raise, in essence having federal funds subsidize low-wage work.

Finally, there are the 300,000 workers whose fate is unknown following the switchover because they can’t be readily identified in the LFS PUMF dataset.

Table 1: The fate of CERB recipients after September 27th

| Pre-September 27 | After-September 27 | Details | |||

| CERB Eligible | 4,017,000 | EI Eligible | 2,111,000 | EI worth $500 or more a week | 789,000 |

| EI worth less than $500 a week | 1,322,000 | ||||

| CRB Eligible | 895,000 | EI claims ran out in 2020 | 232,000 | ||

| Self-employed | 663,000 | ||||

| CRCB Eligible | 181,000 | Quit for child care | 151,000 | ||

| Quit as caring for family member | 30,000 | ||||

| CRSB Eligible | 4,000 | Sick | 4,000 | ||

| No Support | 526,000 | Made over 38,000 in 2020 | 43,000 | ||

| Qualify for EI working while on claim, but receive <$50/wk | 70,000 | ||||

| No other program support | 412,000 | ||||

| Unknown | 300,000 | Unknown | 300,000 | ||

| Total | 4,017,000 | Total | 4,017,000 | Total | 4,016,000 |

The new EI system post-CERB

The EI system will see major changes post-CERB. Specifically, there is a new $400-a-week benefit floor and there is a much lower universal 120 qualifying hours entrance requirement.

Among the 2.1 million CERB recipients who will be eligible for EI, 1.3 million will receive less than $500 a week, which was the CERB amount. However, the $400-a-week floor will apply to 770,000 people, showing just how many Canadians would have received still less had the floor not been in place.

While there are 2.1 million Canadians who will be eligible for EI, there are only 1.3 million who are currently receiving CERB from ESDC, as shown in Figure 1. Those receiving CERB from ESDC will automatically transition to EI.

That leaves 781,000 Canadians who are receiving CERB from the CRA. Those who are on CERB from the CRA will not have their claims ported automatically to EI. They will have to go to the EI website and apply for EI or they will get nothing. There is a real danger of delays and missed benefits for those who mistakenly believe they will automatically be ported into EI.

Table 2 breaks down the type of EI benefits Canadians will likely receive when the system is opened back up on September 27. Interestingly, there are 336,000 people who were not eligible for CERB who will be able to receive EI upon its re-opening. This will be the first income support they receive since the start of the pandemic.

Most of the people who are not eligible for CERB will get access to support through EI’s Working While on Claim. These people lost work, went back to work (but not at their previous level) and make more than $250 a week, which was the CERB cut off. Working While on Claim claws back 50 cents on the dollar, but it doesn’t have a hard cap at $250 a week. So people making, say, $300-a-week can now get support through EI whereas they couldn’t through CERB.

Another 43,000 people will be able to access regular or sickness benefits because they had 120 EI qualifying hours, but they didn’t make $5,000 in the past year. This would be the case for low-paid employees who had just over 120 hours in the previous year.

Most of the CERB eligible Canadians who receive EI post-CERB will receive regular benefits. In addition, 214,000 CERB recipients will receive the EI sickness benefit and another 183,000 will qualify for EI’s Working While on Claim program.

Between those who were CERB eligible and those who weren’t, there are 465,000 workers who will be eligible for EI’s Working While on Claim, a substantial expansion of this program. It is worth noting that an additional 70,000 people will technically qualify for Working While on Claim, but they’ll make less than $50 a week—so little that most likely won’t bother applying.

There are almost 200,000 people who are likely eligible for EI, are employed, but don’t seem to have any working hours. This may indicate that they don’t have all their paperwork in order for EI (like a Record of Employment) and may risk delays in their EI application process.

Average benefits under new programs

While CERB paid a flat rate of $500 a week, as CERB recipients transition to other income support programs, they will move to different support levels, depending on their circumstances.

As shown in Figure 2, over half a million Canadians will get no federal supports after CERB ends—among those, 43,000 will hit the earnings cap on the CRB. Another 210,000 will get something, but less than $400 a week. These are EI-eligible recipients who are working a bit and so their EI payments will get clawed back from the $400 floor.

Close to half (1.6 million) of CERB recipients will get exactly $400, since this is the floor for regular EI payments and it is also the flat amount for those receiving the CRB. Another 184,000 CERB recipients will continue to get $500 a week through the CRSB (but for a maximum of two weeks) and the CRCB. At the upper end, 600,000 people will hit the EI maximum payment of $573 a week.

Across all CERB recipients, they will receive on average $377 a week, or a quarter less than the $500 a week, in post-CERB benefits. This includes what they’d receive through the various EI programs or the CRCB, CRB or CRSB as well as those who’ll receive nothing post-CERB.

It’s worth noting that all these values are on a pre-tax basis. While CERB is taxable, those taxes weren’t deducted at source, so recipients got the full $500 and will likely owe those taxes in March 2021 when they file their taxes.

For EI and the new recovery benefits (CRB, CRCB and CRSB), taxes are deducted at source. Post-CERB, recipients will therefore receive less than $377 a week, on average, because of the tax deduction. The upside is that there will be no tax payment surprises in March 2021.

Figure 2: How much CERB recipients will receive in post-CERB programs

Who’s better off and who’s worse off

Among the 3.7 million CERB recipients with data, 2.7 million (three quarters) will be worse off after CERB—receiving less than $500 a week down to nothing at all. Another 184,000 people will receive the same amount, at $500 a week, while 776,000 people will be better off, since 55% of their previous earnings on EI is higher than $500.

There were 2.1 million women on CERB and 1.6 million men in August. Post-CERB, similar numbers of men and women will be better off—around 400,000 each. However, many more women than men who will still receive $500 a week. This is because the new CRCB will go overwhelmingly to women who are quitting their jobs or cutting their hours in order to care for children whose school or child care has closed. The higher flat value of the CRCB ($500 a week) compared to the CRB ($400) heavily favours women.

There are 1.6 million women who will be worse off post-CERB compared to 1.2 million men. This is mostly due to the fact that there were more women on CERB in the first place. The higher CRCB benefit of $500 offsets the higher number of women who will be worse off, meaning that women’s average benefit will not be dramatically different from men’s when you take all of the programs into account. Specifically, the post-CERB average benefit for women will be $372 a week versus $383 a week for men.

However, the CRCB’s higher benefit could easily reinforce traditional gender roles, pushing women to be the ones to stay home with children since they are often the lower household earner.

Figure 3: Post-CERB better off/worse off by gender

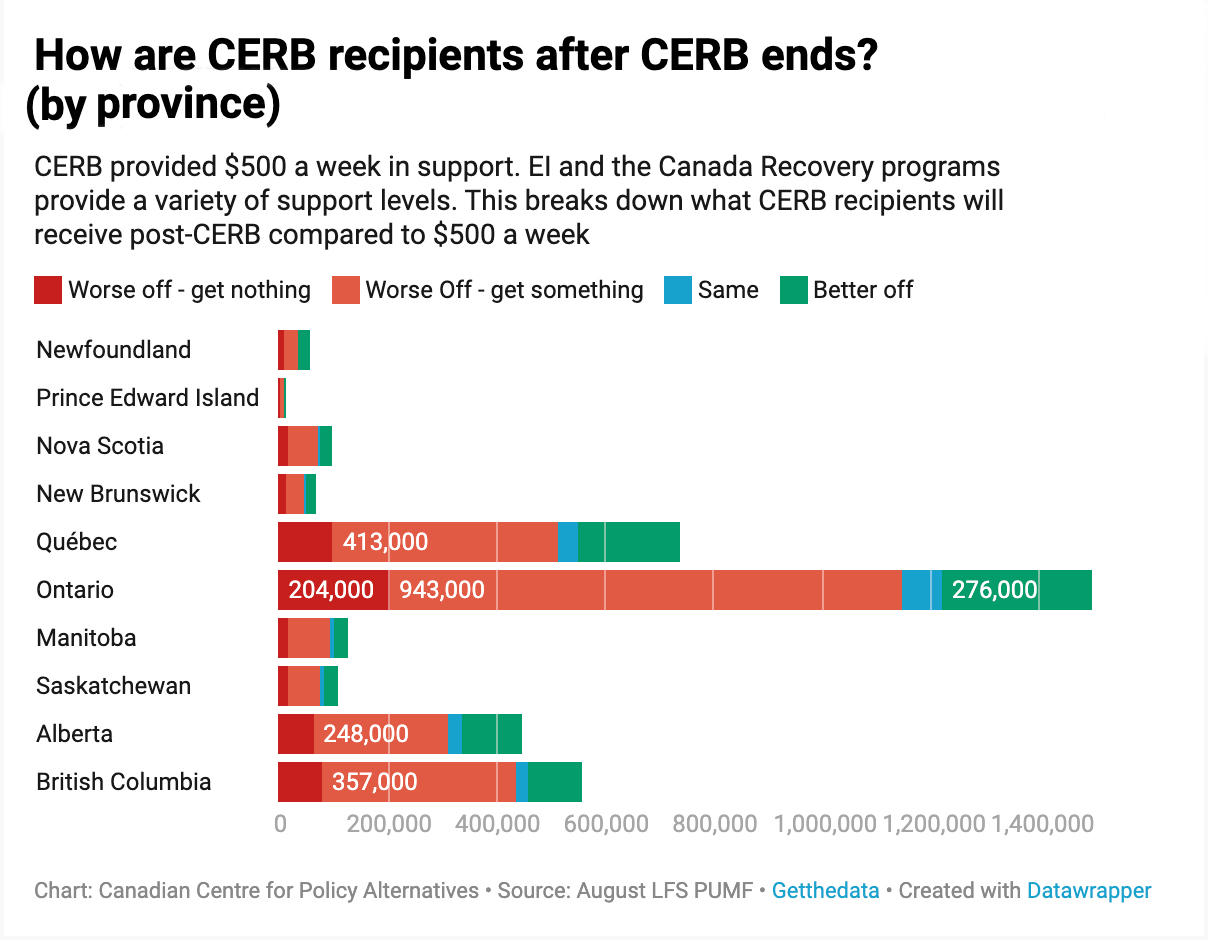

Geographically, most CERB recipients are in Ontario (1.5 million), of which 1.1 million will be worse off post-CERB. Quebec has the second highest number of CERB recipients—512,000 will be worse off after the transition. B.C. will see 437,000 of its CERB recipients worse off after the transition. Proportionately, in B.C. 78% of CERB recipients will be worse off post-CERB, 77% will be worse off in Ontario, and 75% will be worse off in Nova Scotia.

At the city level, the Greater Toronto Area has by far the most CERB recipients, numbering 767,000 in August. Among those, 605,000 people will be worse off after the switchover. This equates to 79% of all Toronto CERB recipients being worse off.

Montreal has the second highest concentration of CERB recipients, with 70% of them—299,000 people—being be worse off after the switchover.

Vancouver has a slightly higher proportion of its CERB recipients who will be worse off, at 80%, resulting in 260,000 CERB recipients who will be worse off.

Figure 4: Post-CERB better off/worse off by province

Figure 5: Post-CERB better off/worse off by CMA

This analysis is premised upon everyone being a documented worker with ready access to the internet and proper paperwork to access these new programs. This includes being legally recognized to work in Canada but, also, being able to rely on an employer to properly submit paperwork, like their Record of Employment. For workers who aren’t documented, none of these supports will apply to them.

Without governmental supports to fall back on, some have been forced into work that no one else will do, assuming health and safety risks for themselves, their families, and communities. For these people, there has been no shelter from the job loss storm. As these undocumented workers are not surveyed for the purposes of the LFS, it is difficult to assess their experience. However, if their experience is similar to other low-wage workers, the probability of job loss or reduced work hours was very high.

Even for those Canadians who are documented, these programs require labour force attachment in the form of recent employment income or hours worked. This leaves out the long-term unemployed, those who can’t work, students (including international students), migrant workers, and recent immigrants. Poverty levels for these groups are often high. The programs discussed in this analysis are not accessible to them, even though their work opportunities and earnings have been greatly diminished by the COVID-19 job market.

Conclusion and recommendations

The transition off of CERB will be an historic one—likely the biggest transfer of beneficiaries from one program to another, following the creation of CERB in April. The timeline is tight and the stakes are very high.

Without modifications, the end of CERB will result in 2.7 million people becoming worse off in the transition. Half a million of them will receive no post-CERB support at all.

While this will squeeze many already tight household budgets, it is much better than the situation would have been without EI modifications and the creation of the new programs. Without them, an additional 2.1 million CERB recipients would be receiving nothing.

Income supports are critical to individuals but, also, to our country’s economic stability and positioning for a recovery. Consumer spending, largely due to the rapid roll out of the CERB, has been mostly responsible for keeping the economy afloat since March.

Beyond highlighting that benefits are lower post-CERB, several recommendations are worth highlighting:

1. EI’s first payment should be on an attestation basis.

To facilitate the switchover to EI, the first EI payment should be on an attestation basis, just like the other new Canada Recovery programs. Subsequent renewals of EI could require the paperwork to be in order, but attestation is one of the reasons the CERB was so successful and it should be imported into EI.

2. Prepare for a comprehensive review to permanently improve EI access and benefit levels.

This review should include a Canada-wide low-hour eligibility rule, a minimum benefit floor for low-pay workers, a reduction in onerous disqualifications, and better access to EI special benefits and training supports for gig and self-employed workers. This should also include a new mandated Consolidated Revenue contribution to the EI Account.

3. There are at least 781,000 CERB recipients who will have to apply for EI. Outreach to them is critical.

These are CERB recipients who are currently receiving their benefit from CRA. They are eligible for EI, but they have to individually go to the ESDC’s EI website to apply. Many Canadians might not realize this and they stand to lose or delay receiving benefits as a result. Outreach to these recipients should be proactive and ongoing.

4. Immediately establish a dedicated “Partners Hotline” and a “Partners Virtual Liaison” on-line service with live callback.

Despite government’s best intentions, the switchover will not go smoothly for everyone. A dedicated hotline for those helping others through the switchover should be established. These would be available to legal clinics, employers, unions and community advocacy organizations that need support with clarifications, trouble-shooting, webinars and similar assistance. These organizations are typically trying to navigate supports on behalf of multiple claimants and could reduce the load on general EI hotlines.

5. EI beneficiaries who exhausted their benefits and could claim CERB should transition to CRB.

Workers with an EI claim that ran out after December 31, 2019 were eligible for CERB—people who became unemployed in 2019, received EI, but their EI benefits ran out in 2020. This analysis assumes that they will be able to transition from CERB to CRB, but that is not explicit in the documentation provided so far.

6. Exercise the utmost flexibility in the administration of the Caregiving Benefit.

At present the conditions for the CRCB are more onerous than those for the childcare portion of the CERB. The CRCB may require adaptations in the coming months as COVID accommodations are a moving target for virtually all schools, childcare services, care facilities and day centres. At the outset, workers who left employment during COVID for caregiving and received CERB should be automatically accepted for CRCB if they affirm their continuing need. This analysis assumes that they will be able to transition from CERB to CRCB, but that is not explicit in the documentation provided so far.

7. EI Working While on Claim should be accessible to those who lost hours but didn’t fully lose work. Claims should be valid if the work interruption occurring before September 27th.

465,000 workers will likely be eligible for EI’s Working While on Claim program, over half of whom were not eligible for CERB. Working While on Claim is only accessible if a worker is fully unemployed and then returns to work, but with reduced hours. If a worker wasn’t unemployed first, but saw a reduction of hours, they are not eligible for working while on claim, except when sickness, quarantine or pregnancy reduces earnings by 60%. EI rules should be modified so that a large reduction in hours due to COVID-19 can also result in a Working While on Claim application. Also, it isn’t clear that workers will be eligible for Working While on Claim if the work interruption happened before Sept 27th. That should be made explicit.

8. Working While on Claim won’t work for 70,000 CERB recipients, since it will provide them with less than $50 a week. A floor should be created.

The Temporary Alternate Earnings rule provided a floor on Working While on Claim benefits of $75 a week, or 40% of weekly benefits, before the clawback began. Re-instituting some version of this alternate rule may be worthwhile given how many Working While on Claim beneficiaries simply won’t apply because the benefit is too low.

Methodology

This analysis uses the August Labour Force Survey, which was conducted between August 9th and August 15th. It simulates the CERB transition as if it had happened in the second week in August. Obviously, these results may change by September 27th, but the September LFS won’t be released by the time the transition happens, so the August data will be the last data point before the switchover.

This analysis utilizes a similar methodology to previous versions. Benefit amounts and eligibility for EI, CERB, CRB, CRCB, and CRSB are not available in the LFS Public Use Microdata File (PUMF). They are imputed based on program rules and characteristics in the microdata individual records. Those records are then aggregated to produce this analysis.

The full methodology is outlined below, but improved on previous versions in the following ways:

Instead of using present job or previous job tenure as a proxy for both EI insurable hours and earnings in the previous 12 months, EI insurable hours are now imputed from the 2018 EI Coverage Survey PUMF based on full-time/part-time status, age, and tenure. This should provide a more realistic picture of both EI insurable hours and earnings in the previous year. If a worker has little tenure in their most recent job, it may mean that they just recently switched jobs—not necessarily that they had a large gap between jobs. This is particularly true for older workers. While this change likely provides more realistic data, the EICS is not the full universe of Canadians. It is restricted to the unemployed, long term jobless, market entrants, and students. This subset may not be representative of all workers who lost their job in 2020.

The LFS contains no information on the earnings of self-employed workers. The only viable place for such information is the 2016 Census PUMF, since the 2018 Canadian Income Survey PUMF contains too little linking information to impute data to the LFS. Weeks worked and annual market income of self-employed workers, adjusted for inflation, are imputed from the 2016 Census individual PUMF to the LFS using full-time/part-time status, occupation, and sex. This should provide an improved measurement of which self-employed workers made over $5,000 earnings in previous year. It also allows for estimation of weekly earnings for the $250/week CERB threshold and whether annual earnings exceed $38,000 the CRB clawback exemption. However, the self-employed labour market has changed significantly since 2015 (the basis for 2016 census employment data), given the explosion of gig work. As such, this imputation may not correctly reflect that change. Lost work due to COVID-19 is likely not randomly distributed even within full-time/part-time status, sex, and occupation also possibly affecting the imputation.

Those receiving CERB for child care was altered to include not only those who quit their job for child care reasons but, also, those who are absent from work for personal of family reasons who had their own children under 13 years old at home, or those who worked part-time due to child care even if they did not have their own young children at home (a grand-parent for example). This substantially expanded the number of people claiming CERB for child care and much of the parental adjustment to the closure of schools and child care resulted in reduced hours—not necessarily lost jobs.

While this is not a change from the previous approach, it is an imputation worth noting. People not employed have no wage rate. If not employed, one’s wage rate is imputed from February LFS wage rates of those in same full-time/part-time status and occupation.

CERB eligibility

In this analysis, workers are deemed to be CERB eligible:If their EI regular benefits ran out after Dec 29, 2019. Eligibility for EI regular benefits is based on EI insurable hours needed and weeks of benefits available for those in <6% unemployment rate regions, as was the national average during 2019. If a person was still unemployed in August and their EI benefits were exhausted in 2020, it is assumed they were CERB eligible.

Or if they became unemployed in March 2020 or later, but didn’t quit (except for child care and illness).

Or if they remained employed but are absent from work and that absence started during or after March, the absence isn’t a vacation, and they aren’t receiving pay during the absence. If the reason for absence is personal or for family reasons and they have a child under 13 years old or they indicated the reason for part-time work is child care, then they are tagged as CERB for child care reasons.

Or If they were making under $250-a-week using actual hours worked x wage rate for regular employees or weekly wage rate adjusted by the reduction of actual hours vs. usual hours for self-employed. The reason for reduced hours can’t be due to vacation. CERB rules require a break in earnings for 14 days. As this isn’t directly available in LFS, it is assumed everyone who saw lowered earnings are CERB eligible.

And if anyone didn’t make $5,000 in the previous year based on EI insurable hours x wage rate or imputed annual earnings if self-employed then CERB eligibility is removed. Unpaid family members are assumed to be ineligible for CERB.

EI Eligibility

Workers are deemed EI eligible if:

They had 120 EI insurable hours and if they were not employed and lost employment on or after March 2020 and didn’t quit for any reason.

Or they have no hours or are absent for work and the absence started in March or later and the reason wasn’t vacation and the absence wasn’t paid. If the reason for lost job or absence is sickness, they are deemed eligible for the EI sickness benefit.

Or they are working but their actual hours in August are below their usual hours and they are not working full-time. In this case, Working While on Claim benefits are calculated using the 50% clawback against weekly earnings until 90% of previous earnings is reached, at which point the Working While on Claim amount is reduced to zero. If working while on claim is less than $50 a week, they are assumed not to apply, as it likely isn’t worth the effort.

EI benefits are calculated as 55% of previous earning (hourly wage x usual hours of total work), with a floor of $400 a week and a ceiling of $573 a week.

New Canada Recovery program eligibility

Workers are deemed eligible for the new Canada Recovery programs if they are not eligible for EI and they have at least $5,000 in earnings in the previous year.

And if they received CERB due to child care, they are CSCB eligible. The criteria for these programs do differ, though. Specifically, the CSCB requires the loss of at least 60% of one’s earnings, and whose children are over 11 years, and the loss can’t be due to voluntarily keeping children home. The CERB requirements were not that detailed.

Or if they were self-employed and lost work due to their own sickness, they are CRSB eligible. While some may be eligible for the CRSB, there are only two weeks of support available for the entire year—meaning that if they switchover from CERB, it will be at the same support level, but only for two weeks.

Or if they were self-employed or have no hours (not due to vacation) and make under $38,000 in 2020, they are CRB eligible.

The $38,000 threshold in 2020 is estimated from weekly inflation-adjusted market income imputed from the 2016 Census. It is the sum of their full weekly pay from the start of 2020 until unemployment or absence from work occurred later in the year. While there is a 50-cents-on-the-dollar clawback for incomes over $38,000, it is assumed applicants wouldn’t bother applying for it if they were already over the threshold by August.

The author would like to thank Laurell Ritchie, Chris Roberts and Mikal Skuterud for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this analysis.

This analysis won Silver in the Best Blog category at the Canadian Online Publishing Awards held in February 2021.