Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

This piece was first published in the Globe and Mail’s Economy Lab.

Five years after a global economic crisis unleashed chaos on markets everywhere, income inequality has become an inescapable political and economic issue, in Canada as elsewhere. That’s because of mounting evidence that the increasingly skewed distribution of gains from economic growth slows future growth potential, and erodes trust that a democratically governed system is working for the benefit of the majority.

It’s a conversation that is heating up in Canada, as two new, articulate voices were added this week to Canada’s federal political scene. Journalists Chrystia Freeland (Liberal) and Linda McQuaig (NDP) – nominated as their parties’ candidates in an upcoming by-election in the high-profile riding of Toronto Centre – will help define how inequality is discussed, both within their respective parties and in the broader public. The stance they will share is that we can’t afford five more years of doing nothing about inequality, and that current federal policies widen the income gap.

Respected pundits, such as Andrew Coyne, have been quick to say that though inequality is a legitimate political issue in the United States, there’s no reason to get fussed about it in Canada.

If we compare ourselves with the U.S., indeed we have little cause for complaint. No one does extreme like the Americans. Only Turkey and Mexico outstrip U.S. levels of income inequality among OECD countries, and they are both closing the gap. In contrast, income inequality in the U.S. just keeps rising. A recent study by the pre-eminent researcher of international income inequality, Emmanuel Saez, shows that a stunning 95 per cent of all income gains between 2009 and 2012 went to the top 1 per cent of earners in the United States.

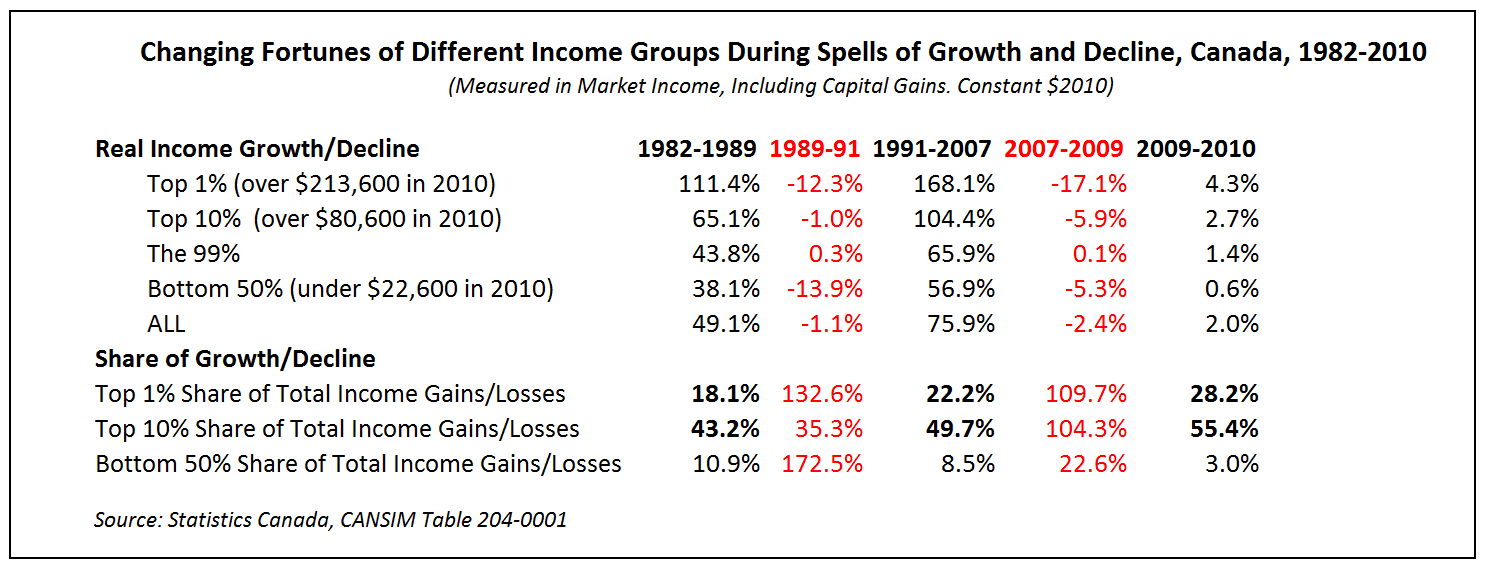

Canada’s story pales in comparison – and so does our access to comprehensive and timely public data about the top 1 per cent. But the data we do have reveal the same troubling trends. In each phase of economic expansion since the 1980s, the top 1 per cent of Canadian tax-filers took a bigger share of income growth, and less of the hit in bad times. (The top 1 per cent always sees a big decline in incomes during a recession, but in the 2008-2009 recession more of the pain was shared with the rest of the top 10 per cent.)

But incomes have indeed grown since 2009, and thus far the top 10 per cent enjoyed more than half of all that growth – and the top 1 per cent alone accounts for more than half of that. Welcome to the recovery. The higher up the income ladder you are, the more you benefit from economic growth.

As one wag put it: Trickle-down would work if it weren’t for the sponges at the top.

Canada and the world have entered a period of subdued economic growth, partly self-inflicted by governments’ deficit-reduction programs. Slower growth spells more friction, as the increasingly tilted distribution of gains from growth becomes increasingly obvious. For too many people, the gains from growth happen somewhere else, for someone else.

If the standard-issue business response to slowing growth in profit margins is further cost-cutting – labour costs, primarily – expect to see more friction. If governments implement policies that actively widen the income gap – such as the majority of tax cuts, increased use of temporary foreign workers, and legislation that curbs workers’ bargaining power – expect to see more friction.

The Occupy protests have come and gone, but “We are the 99 per cent” is now part of the lexicon – it changed how we view the economy and the very purpose of growth. A legacy of the 2008 global economic crisis, talk of “the 1 per cent” isn’t about envy. It’s about an emerging awareness of a new dynamic between the many and the few. The conversation that started five years ago will reverberate through political and economic debates for years to come.

Armine Yalnizyan is a Senior Economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow her on Twitter at @ArmineYalnizyan.