The USMCA, or CUSMA as it’s known here in Canada, is slowly working its way through the U.S. “fast-track” ratification process. Once the U.S. International Trade Commission tables its required economic impact study, delayed by the month-long U.S. government shutdown, the Trump administration will present Congress with implementing legislation. But few expect it to go smoothly.

The Democrats, who now control the House of Representatives, are in no mood to simply rubber-stamp Trump’s NAFTA replacement, handing him bragging rights in advance of next year’s elections. They will likely insist on putting their own mark on the deal by demanding stronger enforcement of labour rights and changes to intellectual property provisions that would lock in sky-high U.S. drug costs.

Although both these reforms would benefit most Canadians—and bring the new NAFTA more into line with Prime Minister Trudeau’s avowed “progressive trade policy” vision—our federal government continues to publicly insist that the deal is final and can’t be reopened.

Bad trade rules fuel high drug costs

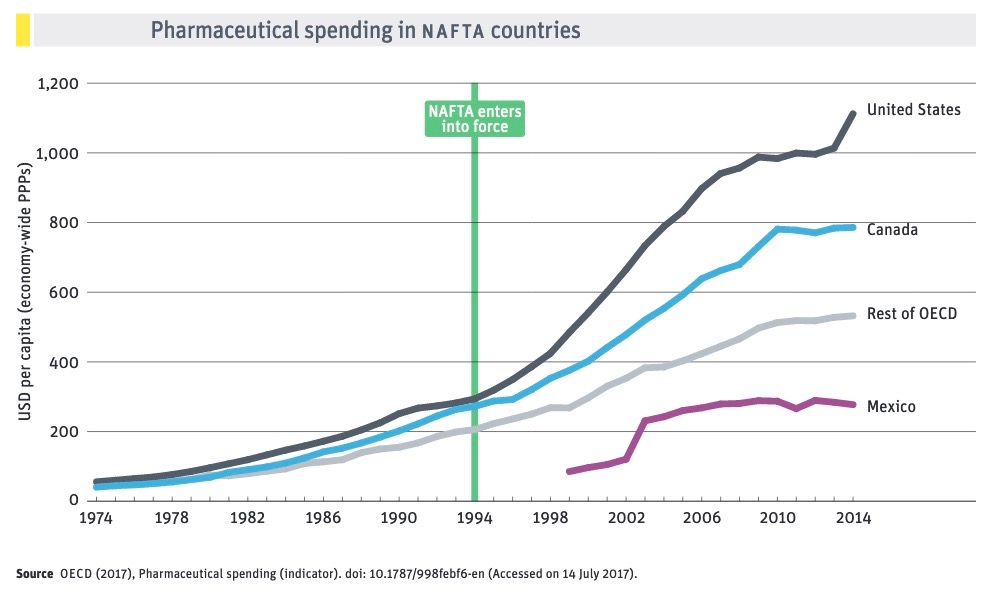

The determination with which the crop of freshly elected House Democrats have taken up the issue of controlling rising drug costs should hearten public health advocates in all three countries. Beginning in the mid-1990s with NAFTA and the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), corporate lobbyists seized on free trade agreements (FTAs) as tools to expand intellectual property rights.

Intellectual property rights (IPRs) are the antithesis of classical free trade because they severely restrict competition. Yet this hypocrisy has done little to slow their expansion through FTAs. By creating and expanding legally sanctioned monopolies, IPRs boost rightsholders’ profits and market dominance. Not surprisingly, these corporate gains come at the expense of consumers and the public interest.

The impact of expanding IPRs on public access to affordable medicines was deliberate and foreseeable. Drug costs rose as the availability of less expensive, equally effective generic medicines was delayed or denied. Every extra year that brand-name companies can charge monopoly prices boosts their profits. By delaying access to more affordable generic versions of brand-name drugs, longer patent terms and other forms of monopoly protection increase costs to consumers and health care systems. Particularly in developing countries, poor and struggling populations are being denied access to essential medicines.

USMCA’s monopoly protections for biologic medicines

The USMCA is simply the latest example of Big Pharma using trade agreements to boost profits. If implemented unchanged, the agreement would expand monopoly protections for multinational brand-name drug firms, benefitting highly profitable corporations at the expense of consumers and public health systems. The deal sets new high-water marks for industry-friendly IPRs in several areas, most notably data protection for biologic medicines—drugs derived from living organisms such as human or animal cells.

Data protection refers to the period of market exclusivity (monopoly) during which competitors are denied access to data related to clinical trials done by the company in order to have the drug approved by regulators (Health Canada in this country). Generic drug firms need access to this test data to produce cheaper versions, known as biosimilars.

USMCA provides for a minimum of 10 years of data protection for biologic medicines. This was a key demand of Big Pharma. Biologic medicines are among the most expensive and profitable class of medicines. For example, popular biologics to treat rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease can cost $20,000 to $30,000 yearly. The costs for certain biologics designed to treat rare diseases can be substantially higher. Biosimilars can significantly lower these costs, increasing access and stretching health dollars farther.

Ten years is a longer term of data protection than what has been required under any previous FTA. Canada currently provides eight years of data protection (plus six months if the clinical trials involve children). Even before the USMCA, Canada’s data protection provisions were among the most industry-friendly in the world.

Although they are sometimes confused, patents are distinct from data protection. The term of patents extends from the date of filing, while the term of data protection begins when the drug receives market approval. Since patent terms are longer than those for data protection, the price impacts of the USMCA changes will be felt where new medicines are either not protected by patents or their patent protection expires in less than 10 years from market approval.

USMCA’s impact on drug costs

Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) has released the first study that attempts to quantify the financial impacts of these longer data protection provisions for Canada. Biologic drugs are already eating up a larger share of prescribed drug spending, and the PBO report discusses the reasons this amount is expected to rise in future.

The PBO estimates “that the CUSMA-induced increase in expenditures for consumers and drug plans would amount to at least $169 million in 2029, increasing annually thereafter.” The PBO flags that this figure underestimates total costs because it does not include drugs administered in hospitals and clinics.

Estimating future price impacts involves making key assumptions about future sales of biologics (the higher the sales of the brand-name medicines, the greater the potential savings from competition); the uptake of biosimilars (the higher the market penetration, the greater the savings); and the price discount (the larger the discount, the greater the savings).

The PBO estimates are based on a discount of 30%, an uptake of 75%, and biologic sales in 2028 of $13.1 billion (of which $3 billion would benefit from longer data protection). Also, as the report explores in its annexes, modifying the underlying assumptions can greatly change the estimates of costs, which range from a low-end scenario of $16.9 million annually to a high of $372 million annually.

While currently there are only a limited number of biologic drugs that would benefit from extended data protection, the PBO report notes that “significantly more drugs could be impacted in the future.” The prospect that pharmaceutical firms will rely more on data protection to acquire market exclusivity creates an acknowledged “downward bias” in the PBO estimates.

This PBO analysis is a follow-up to its earlier report on the impacts of the Canada–EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), which took effect in September 2017. CETA included a system of patent term restoration that added up to two years to the term of monopoly patent protection. The PBO estimated the additional costs to Canadians (public and private health plans, consumers and hospitals) at over half a billion dollars annually.

Liberal U.S. Democrats to the rescue?

During the USMCA negotiations, the Canadian government firmly opposed longer terms of data protection for biologics, but its opposition cratered after the U.S. deal struck with Mexico in August 2018 included longer terms of data protection, and other aggressive U.S. demands, in its full-fledged intellectual property chapter. The Canadian government is now against reopening USMCA, fearing the whole deal might unravel.

Nevertheless, Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives may yet come to the rescue of Canadians. The Democrats were elected on promises to lower exorbitant U.S. drug costs and are not keen to lock in higher prices through the USMCA. Various proposed bills include reforms to shorten the U.S. term of data protection (currently 12 years) to five or seven years. With support from the 90-member strong Congressional Progressive caucus among others, the idea is gathering steam. But if ratified unchanged, the USMCA would tie Congress’s hands.

A growing number of Democrats say they will vote against ratifying USMCA unless the change is made. If they are successful in shortening the term, this would clearly benefit Canadian governments and consumers. Since the Trump administration needs Democratic support to get USMCA ratified, it may have to bend to demands to reopen the deal and change these provisions.

Fixing Canada’s dysfunctional drug price controls

Canadians fed up with high drug prices should take heart from the rising pushback in the U.S. against Big Pharma. While changes to USMCA depend mainly on developments south of the border, the PBO report identifies a key domestic reform where big savings could be at hand.

Canada’s current system of price regulation for brand-name drugs is dysfunctional and locks in high prices. Health Canada had proposed to fix this by changing the way our price controls work. Currently, the Patent Medicines Prices Review Board sets prices with reference to the average costs of seven countries. Prices are then allowed to rise at the general rate of inflation. But those seven countries include the U.S. and Switzerland, which pulls the average up. By excluding these two high-price outliers, and through other changes to pricing criteria and drug company transparency, Health Canada estimates it can reduce Canada’s drug costs by an average of $1.2 billion a year over the next decade.

Big Pharma is, of course, apoplectic. The savings from Health Canada’s recommended changes to price regulation would more than offset the brand-name companies’ increased profits from extending patents and data protection under CETA and USMCA. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America is urging the U.S. Trade Representative to take immediate action, up to and including trade sanctions, if Canada dares to proceed. And the federal government is already dragging its feet on these urgently needed reforms.

Despite these ugly threats, it is high time for Canada to step off the treadmill of ever-increasing intellectual property and monopoly protections for these highly profitable but insatiable corporations. Canadians should welcome the growing opposition in the U.S. to trade deals locking in high drug costs. It will be a good start if Democrats are successful in diluting data protection for biologics in USMCA.

Yet, even with the proliferation of excessive intellectual property protections in trade deals, our federal government still has the power to implement effective price controls. What it needs is the courage to stand up to the powerful pharmaceutical industry lobby on behalf of Canadians.

Scott Sinclair directs the CCPA’s Trade and Investment Research Project.