This analysis has been updated following federal legislative changes. Read the update here. Please note we are unable to assist individual CERB/EI recipients with their claims. We encourage you to contact your Member of Parliament’s office for assistance with your file. To find your Member of Parliament and their contact information, visit the Parliament of Canada website and type in your postal code. We are working to compile a list of resources for CERB/EI recipients affected by the switchover but encourage you to contact your MP’s office in the meantime as they are able to assist with claims.

Fast Facts

- As of August 2, 4.7 million Canadians were receiving the CERB.

- Based on the July Labour Force Survey (LFS), 1.4 million CERB recipients are eligible for EI under existing EI rules.

- Of that group:

- 811,000 would receive EI but would get less than $500 a week;

- On average, those making less on EI would receive only $312/week; and

- 493,000 women and 320,000 men would be worse off on EI compared to the CERB.

- Also based on the LFS, 2.1 million CERB recipients are not eligible for EI under existing EI rules.

- Upcoming EI rule changes will determine how many of those 2.1 million CERB recipients will be left behind in the switchover to EI.

- 57% of CERB recipients at risk of being ineligible for EI are women.

- Without changes, 82% of people receiving the CERB (2.9 million) will be worse off on EI, either receiving less or nothing at all.

The federal government recently announced it would be transitioning Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) recipients back to employment insurance (EI) in September. The final CERB period ends August 29. The prime minister committed that “no one will be left behind” in the switchover to EI.

As outlined in the Alternative Federal Budget COVID-19 Recovery Plan, it’s time for the CERB to end, but it’s also time for the best aspects of the program to be imported into a modernized EI system for the 2020s, not the 1970s. The danger in this transition is that if it’s done wrong, millions of people will indeed be “left behind.” The following analysis shows exactly how high the stakes are in this transition.

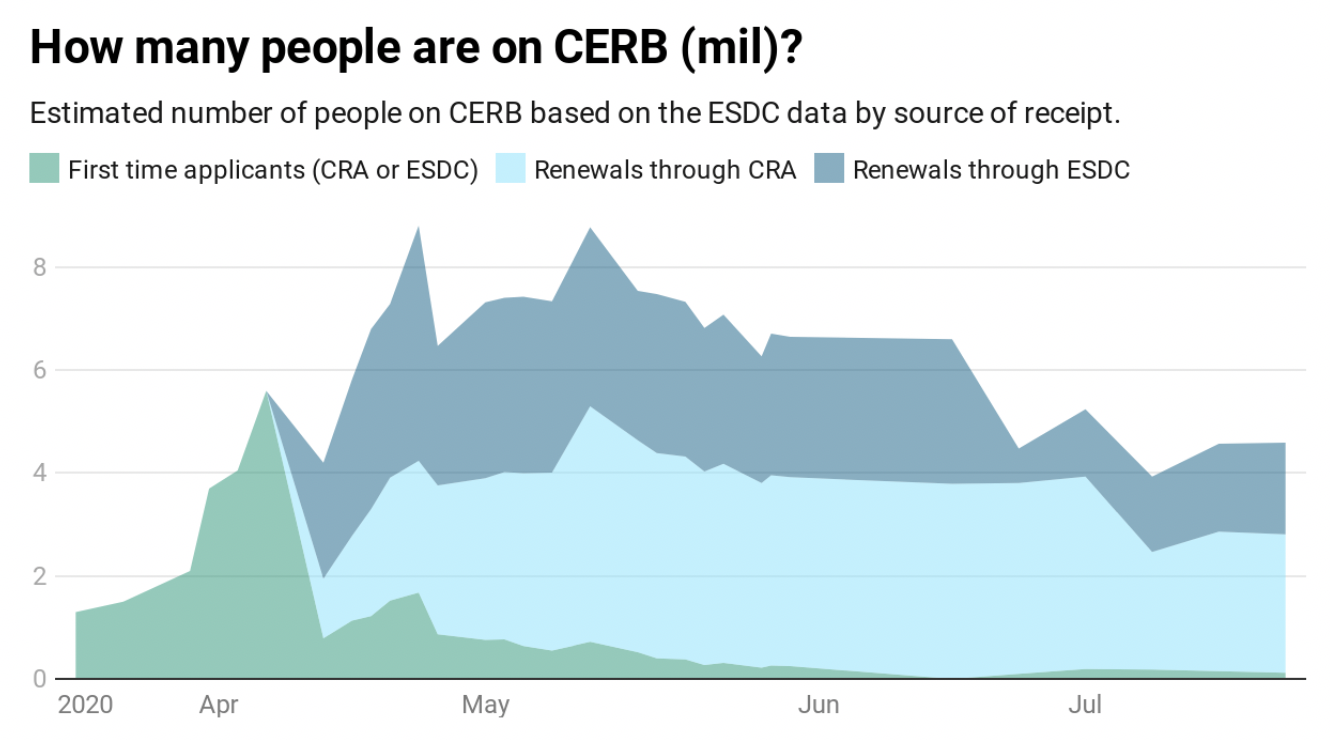

First of all, it’s important to estimate how many people are likely to go through the CERB-to-EI switch. Government statistics only count the unique number of people who received the CERB over the life of the program (8.5 million). But this isn’t terribly useful, as people may have only received the CERB a month in April but then gone back to their jobs in the summer. We need to know how many people renewed their CERB payments recently to know how many will likely roll over to EI in September.

My best estimate is that at the start of August there were 4.7 million people receiving the CERB (you can see how I arrived at that number in the methodology section below). That figure will hopefully fall by the end of August as we see the job market recover a bit more. By the end of July almost all CERB recipients were renewing pre-existing claims instead of making first-time applications.

However, 4.7 million people is a lot of people—about 10 times more than what the EI system supported in February 2020 (443,000 people) before COVID-19 substantially hit Canada.

The LFS isn’t a perfect match to the CERB data, for instance the CERB data suggests 4.7 mil recipients on Aug 2nd whereas the LFS data suggest 3.5 mil CERB eligible workers in mid-July. However, while the LFS can identify fewer of the CERB eligible workers, it can be used to get a better sense of the size of various groups at risk of losing benefits if we don’t get the transition from CERB to EI right (see methodology section). Since we don’t know the extent of the EI rule changes being considered by the federal government, the analysis below assumes that no changes are made in order to clarify what is at stake. The analysis below relies exclusively on the LFS data.

First of all, 41% of people receiving the CERB (1.4 million people) would be eligible for EI without any rule changes, which roughly reflects the proportion of the unemployed that EI generally covered before COVID-19. The biggest issue for CERB recipients who are already EI-eligible is that they’ll move from the CERB’s flat $500/week to EI’s 55% of previous earnings.

For most of the people rolling to EI, they’ll actually receive much less in EI benefits than they got from the CERB. On average, the 811,000 people whose EI payment will be less than $500 a week will make only $312 a week. In other words, over three quarters of a million people will see their support drop by an average of almost $200 a week. For another 625,000 people, they’ll make more on EI than the CERB as they were higher earners (since March 15, any application for regular EI benefits was turned into a CERB application).

Without EI rule changes, 2.1 million CERB recipients would be completely cut off when the program ends. The largest group who wouldn’t be eligible are those who are still working. There are 972,000 people who make less than $1,000 a month and therefore can receive CERB but wouldn’t be able to receive EI, as you have to be completely unemployed with no wage income to get EI (except in some work-sharing situations and if working while on claim). An expanded working-while-on-claim program might be one avenue that could allow people to earn some money while on EI.

Next, there are 553,000 people who are technically employed but have no hours. This group isn’t on layoff, they aren’t on vacation and they aren’t on any other sort of leave; their only unique feature is that they usually have hours and in July they had none. It is unlikely that these workers received a layoff record of employment (ROE). Without a ROE they can’t apply for EI, although they could have received the CERB. This is perhaps the group most likely to be “left behind” as they may believe that they’ll receive EI but don’t realize they’ll have to go back to their employer, ask to be officially laid off, get a ROE proving it, then go back and apply for EI. Changing EI from a ROE to an attestation basis would help with this transition, but there seems to be little indication that this move is in the works.

Unlike the CERB, EI never covered gig or self-employed workers who lost their employment, of which there were 391,000 in the mid-July LFS data. The government is suggesting these workers will be covered under new EI rules, or perhaps be granted some sort of transitional benefit like the one for seasonal fishers.

There are 156,000 people who made $5,000 in the past year before becoming unemployed due to COVID-19. These people could get the CERB, but there are many who didn’t have the number of hours required in their EI region to be eligible for EI—generally workers with higher hourly wages who made the income threshold of the CERB but not the hours threshold of EI. Without a reduction in the hours required to get EI (to roughly 300) these folks will be left behind.

Finally, there are 18,000 people who were forced to quit due to a lack of child care during the pandemic. This figure seems low and is based on a multiple-choice list in the LFS that includes other reasons, several of which might apply. The actual figure is likely much larger than this. CERB allowed people to stop working to look after children, but EI does not. There are indications that EI rules may be changed to accommodate these additional situations of family caregiving, including children at home due to the current uncertainty about child care and schools.

The fate of CERB recipients

|

|

Count |

|

Count |

|

Eligible for EI |

1,528,037 |

Get EI worth <$500/week |

940,651 |

|

Get EI worth >=$500/week |

587,386 | ||

|

Not eligible for EI |

2,390,475 |

No EI: Are working making under $1,000 a month |

967,741 |

|

No EI: Self-Employed/Gig workers |

516,432 | ||

|

No EI: Not enough hours for EI |

187,752 | ||

|

No EI: Parents forced to cut hours/quit as kids not in school/child care |

14,076 | ||

|

No EI: Still Employed but with no hours |

704,474 |

Note: Assumes no EI rule changes (see methodology below for more details). Data is from the July LFS and will have changed by the end of August when the switchover happens.

There is an uneven distribution among people who will receive less on EI than they did on the CERB. In general, women fare worse. Of the women who are receiving the CERB but are already eligible for EI, 62% will see a drop in income support, but only half of men will receive less on EI. Of the 811,000 CERB recipients who will be worse off on EI, 492,000 of them are women and 299,000 of them are men.

Among those at risk of not being eligible for EI at all, 57% are women and 43% are men. In other words, 1.2 million women are at risk of receiving nothing after the switchover compared to 908,000 men.

In conclusion, the stakes are high in the switchover from the CERB to EI, which comes at a time when it is clear the pandemic and its related economic impacts are far from over. Without modifications, 82% of people receiving the CERB, 2.9 million Canadians, will be worse, receiving less from EI or nothing at all. The following EI rule changes taken from the AFB Recovery Plan EI chapter can substantially reduce that number:

- Create a floor on benefits of $500 a week or increase the replacement rate to 75% of income for those who are EI-eligible but didn’t make much before being laid off.

- EI should move to an attestation basis for the first payment, which will help those who might not have their official layoff paperwork in order.

- EI qualifying hours should be reduced to a universal 300 over the prior year.

- EI should be altered to cover gig and self-employed workers.

Without these changes, many unemployed Canadians, particularly women, are at risk of even less support and lower incomes in the worst job market since the Great Depression.

Methodology

CERB recipients

Data on the total number of people receiving the CERB on a given date isn’t available. On a semi-regular but ad hoc basis, the government updates these three variables from the ESDC CERB site: total unique applicants, total applications processed, and total dollar value of CERB benefits paid. The CERB could be accessed through either ESDC’s EI portal and renewed for $1,000 every two weeks, or through the Canada Revenue Agency’s portal and renewed for $2,000 every four weeks.

From these three variables it is possible to calculate four additional variables in any period: new CRA applications, new ESDC applications, ESDC renewals (through the EI portal), and CRA renewals. The calculations are based on the following three formulas:

- c=n*2000+r*2000+i*2000+l*1000,

- a=n+r+i,

- u=n+i

Where:

c = total dollar value of CERB benefits paid

a = total applications processed

u = total unique applicants

n = new applications through CRA

r = renewals through CRA

i = new applications through ESDC

l = renewals through ESDC

This equation set yields unique solutions for r and l. A third unique solution is possible for n + i, meaning we can’t reliably disaggregate new applications to CRA from new applications to ESDC. Using privately obtained information for the period covering March 15 to May 28, 47% of new CERB applications were through ESDC and 53% through CRA, and for this analysis that constant ratio is used in all periods. Over each period n, i, r and l are calculated and the total number of people receiving CERB is the sum of anyone who applied through ESDC (either new or renewal) over the past two weeks or applied through CRA (either new or renewal) in the past four weeks. The data above is as of August 2. Additional details are available from the author.

CERB and EI eligibility

There is not a standard dataset to examine exactly who is eligible for the CERB or EI. These variables must be calculated using other available variables in the LFS PUMF from July 2020. Those who are eligible for these programs based on LFS variables may not actually be receiving benefits, either because there are other reasons that disqualify them or because they didn’t apply. As such, comparing EI and the CERB can only be done on an eligibility basis.

For those presently employed, usual hours and hourly wages are available. In conjunction with job tenure these variables determine if one has enough hours to qualify for EI, if one has made $5,000 in their present job, their usual weekly earnings (as the basis for the EI benefits), and so on. However, for those unemployed or out of the labour force, usual hours and hourly wages are not known. What is known are part-time or full-time job status from a previous job, tenure of the previous job, and occupation. A person’s missing wages and usual hours worked are imputed based on the average of someone with the same full-time/part-time status working at the same occupation in February 2020.

EI eligibility uses a three month rolling average to determine the hours one had to have worked in the previous year to qualify. This is calculated across the 64 EI regions. The LFS PUMF only contains eight of those EI regions as census metropolitan areas (CMAs). It does contain any part of a province not in those CMAs. An average three-month rolling unemployment rate is derived for those “not in a CMA” areas of each province. Otherwise the three-month rolling average in that CMA is used to determine worker eligibility for EI. The appropriate month when someone became unemployed is used to set the EI hours eligibility threshold, meaning it will be harder for someone to get EI in March when the three-month unemployment average was still very low compared to July when it would have adjusted downward.

The actual amount of time a worker has been continuously working is not known in the LFS; all that is known is how long they’ve been in their present job and that is what is used to determine CERB and EI eligibility. However, this assumption will likely underestimate the number of people actually eligible for either program as workers often move from one job to another without interruption, meaning the tenure at the present job underestimates the duration of continuous work.