Source: Making decarbonization work for workers (Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives)

Who deserves a Just Transition to a cleaner economy? Coal miners, of course! Maybe steel workers, too, and truck drivers? Actually, all working people — and their families — probably need some support. So do the public services they depend on. Perhaps the whole economy needs a Just Transition. But wait, I thought this was about the coal miners?

As it turns out, deciding who is included in the Just Transition conversation is a more complicated question than it first appears.

In every articulation of the Just Transition concept, there is a threshold (either explicit or implicit) for who is vulnerable and, therefore, who deserves support. Few Just Transition advocates have explored what it means to provide targeted programmes to people on one side of this line but not to people on the other.

As governments increasingly take up the Just Transition cause and start putting money into social projects and programmes, these equity considerations need to be put at the forefront of the conversation.

A closer look at Canada’s fossil fuel workforce

Our recent research on the Canadian fossil fuel industry highlights some of the potential challenges to Just Transition policies from an equity perspective.

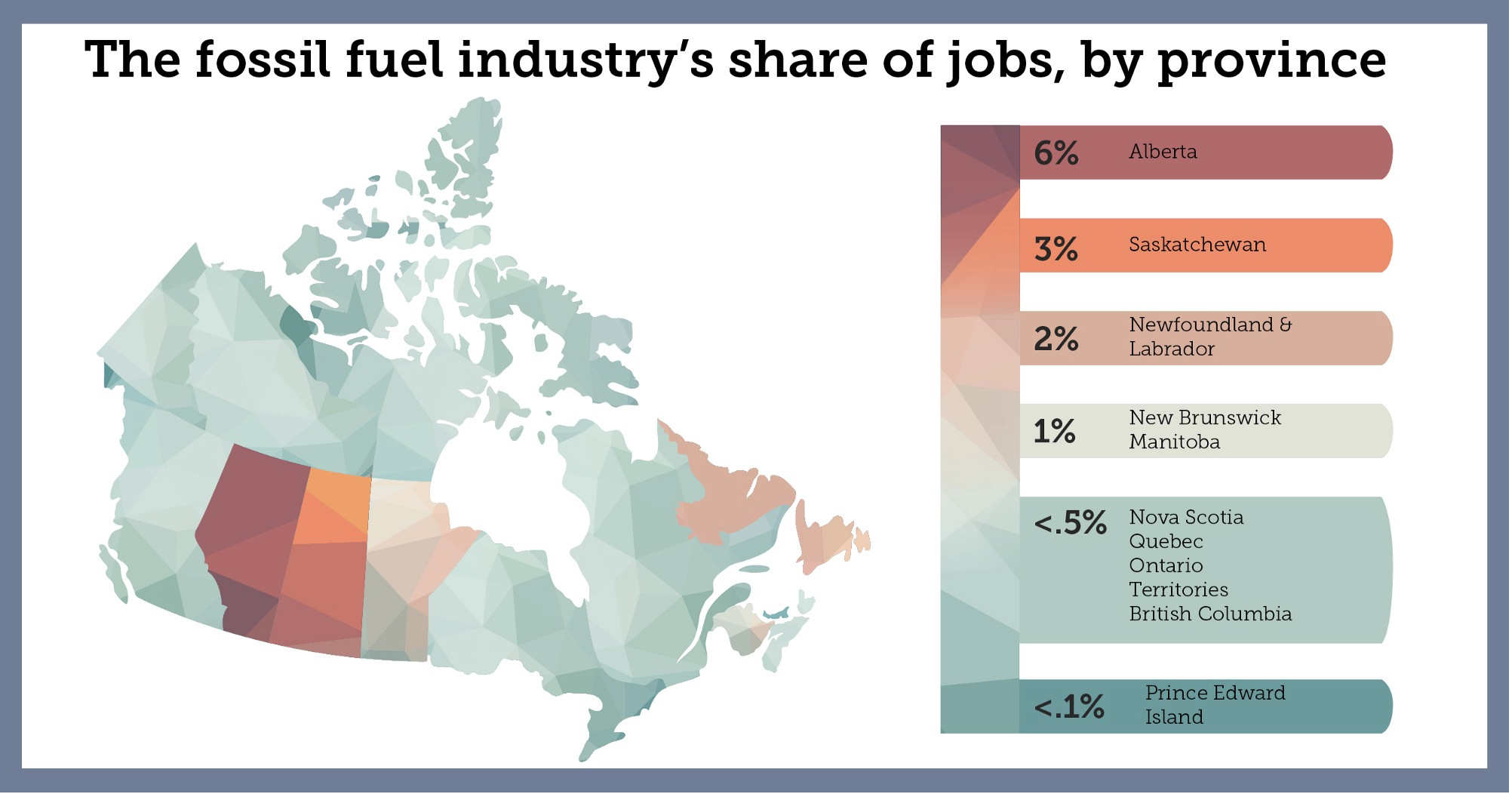

First off, Canada’s fossil fuel workforce is extremely geographically concentrated. More than two thirds of oil, gas and coal jobs are in the province of Alberta. In the city of Fort McMurray, which is famous for its oil sands industry, one in every three workers is directly employed in the oil sector.

Second, the fossil fuel industries are overwhelmingly male. Fewer than a quarter of oil, gas and coal workers are women. Conversely, the service sectors in oil and gas towns are predominantly female.

Third, fossil fuel workers make an average of CAD$141,000 in total income annually, which is nearly triple the Canadian average. The people providing food and accommodation services in fossil fuel communities earn on average just CAD$30,000 per year.

Fourth, those well-paid fossil fuel workers are almost entirely Canadian-born. Only 12% of oil, gas and coal workers are immigrants, even though immigrants make up 23% of the Canadian workforce. On the other hand, 40% of those poorly-paid service workers are immigrants.

Now consider a hypothetical government programme to provide direct income supports, retraining programmes and benefit protections to Canadian fossil fuel workers, which is broadly consistent with proposals from many Just Transition advocates.

In effect, the government would transfer a sum of money to high-income, Canadian-born men in Alberta while they relocate or train for jobs in cleaner industries. The low-income service workers in those very same oil and gas towns — most of whom are women and many of whom are immigrants — would receive no support even though they are ultimately dependent on the same industry for their livelihoods.

Fossil fuel communities in Canada are already among the most unequal parts of the country. Implementing Just Transition programmes that empower privileged workers without proactively addressing marginalization will make things much worse.

To be clear, such a brazenly inequitable policy programme is not in place in Canada. Where governments have implemented targeted Just Transition policies, such as Alberta’s Coal Workforce Transition Fund, they have also provided broader supports to affected communities.

Furthermore, the mere existence of inequality is no reason to withhold supports for workers in the fossil fuel industry or other affected sectors. On the contrary, Just Transition programmes that provide supports to all workers and communities at a level commensurate with their needs can go a long way toward addressing these problems.

Nevertheless, this hypothetical example illustrates how a failure to put equity considerations first may result in policies that ignore the people most in need of support.

Putting the “just” in Just Transition

Like every part of the world, Canada faces unique challenges in the transition to a low-carbon economy. Not every country has a large fossil fuel industry put at risk by climate policies, and not every country faces the same stark inequalities in vulnerable regions.

Yet every country must reckon with the extensive economic changes that decarbonization requires. If a productive, equitable outcome for all workers is a priority in that transition, then we must look beyond the immediate impacts on fossil fuel workers and consider who else deserves support.

Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood (@hadrianmk) is a researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, where he focuses on international trade and climate policy, and a contributor to Adapting Canadian Work and Workplaces to Respond to Climate Change. The figures in this article come from his new report “Making decarbonization work for workers: Policies for a just transition to a zero-carbon economy in Canada,” published jointly by ACW and the CCPA.

This think piece is part of the Just Transition(s) Online Forum.