Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $60 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

Today the Leader-Post published my response to Minister Gord Wyant’s recent op-ed that argued the Saskatchewan government would continue to use the P3 model for certain new public infrastructure.

In that response, I noted that politicians have fallen in love with the P3 model because it allows them to push debt way down the road, with bills that come due long after they have left office. Given the constraints of a letter to the editor, I wasn’t able to adequately illustrate how this works.

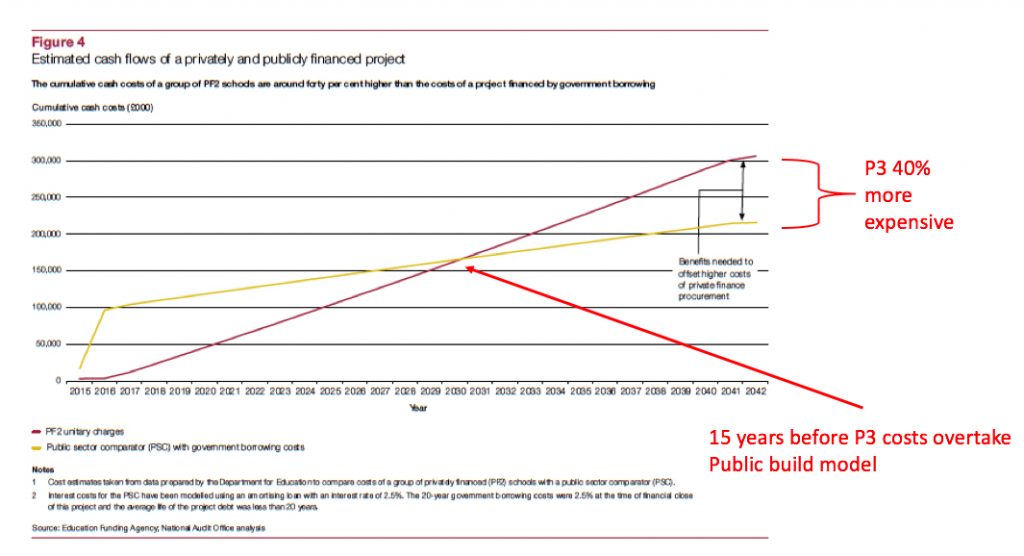

Luckily, the United Kingdom’s National Audit Office (NAO) provides a useful visual that starkly demonstrates why the P3 model is good for politicians, but not so great for the rest of us. As we can see below from the NAO’s analysis for a P3 school build, the public model has a larger initial outlay of funds versus the P3 model, but over time, the P3 payments surpass the public model in cost until it becomes 40 percent more expensive in total.

But it takes 15 years for P3 payments to surpass the cost of a traditional build. Given that the average career of a politician is about eight years, most politicians will be long gone when the true nature of the cost is finally realized. This is why the U.K. example is so useful, with 30 years of experience with the P3 model, it is one of the first countries to show the long-term impacts of using the P3 model on the public purse.

And the results are not pretty, saddling the government with almost £200 billion in P3 debt until 2040. Little wonder that the U.K government decided to abandon the P3 model altogether, citing its significant fiscal risk for government. The Saskatchewan government would do well to follow the U.K.’s example.